A ‘Notorious’ Champion of Women

How Ruth Bader Ginsburg revolutionized gender equality law in the 1970s.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

PERSISTENT: Ginsburg in 1977, during a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship in Italy.

by Philippa Strum ’59, P’98

“I was just lucky to be in the right place at the right time,” Ruth Bader Ginsburg said. But, in fact, that wasn’t the whole story.

It was 2012, and we were in her Supreme Court chambers, talking about the pathbreaking cases she won in the 1970s arguing as an attorney before the court on which she now sat, cases that upended American law by putting gender equality into the U.S. Constitution.

Ginsburg’s brilliant legal strategy led to that milestone for women, not timing. Yet it was true, as she frequently noted, that earlier generations of women had made many of the same arguments she made: That prevailing stereotypes about the proper roles for men and women discriminated against women. That those stereotypes hurt men as well. And that laws designed to “protect” women simply made women frustratingly unequal.

Unfortunately, as she often said, earlier generations spoke up “at a time when no one, or precious few, were prepared to listen.”

In 1971, Ginsburg began litigating against sex discrimination. And in less than a decade, the indefatigable RBG would persuade a male judicial system to recognize, at long last, the truth of what women had been pushing for for years.

A two-pronged attack

To do that, she had to overcome two challenges.

Born in Brooklyn in 1933, Ginsburg graduated first in her class from Columbia Law School in 1959 and started teaching civil procedure at Rutgers Law School in 1963. By the late ’60s, at the urging of her students, she decided to introduce something radical: a course on women and the law in America. To prepare, she read everything she could find on the subject.

What she discovered, she recalled, was that the U.S. Supreme Court “never saw a gender-based classification it didn’t like or regarded as unconstitutional.” This was true in 1873, when the all-male court told Illinois resident Myra Bradwell it was rational for a state to deny her or any other woman a license to practice law.

It was equally rational, the court declared in 1875, for a state to deny women the right to vote.

The arrival of the 20th century did nothing to change the justices’ thinking about rationality. In 1948, the Supreme Court told Valentine Goesaert, who had inherited her late husband’s bar, that it was rational for a state to prevent women from running a bar (effectively agreeing with the all-male Michigan Bartenders

Union, which had argued that “liquor alone causes enough trouble. Why add women?”). And as late as 1961, the justices still found it rational for states to prevent women from serving on juries.

“Rational” was the key word. When a classification on the basis of sex came before the justices, they asked if there was a rational relationship between the object of the law and the decision to categorize men and women differently.

The court’s answer was it was as rational to keep women out of courtrooms, where they would hear things no decent woman should be exposed to, as it was to keep the delicate creatures from running bars.

So in 1971, when Ginsburg started litigating sex-discrimination cases, her first challenge was to convince the courts the proper test was not “rational relation” but “suspect classification,” which was the test the Supreme Court used in cases of alleged race discrimination. There, the justices relied on the assumption that laws classifying people on the basis of race were “suspect” and presumptively unconstitutional.

The suspect classification test put a difficult burden of proof on the government defending the law. Getting the justices to apply that test to sex discrimination would depend upon showing them sex was as poor a reason for distinguishing people as race was.

Ginsburg got her opportunity in the case of Reed v. Reed, which went to the Supreme Court in 1971. Sally and Cecil Reed were the Idaho-based divorced parents of a teenage boy nicknamed Skip. Although Sally had custody of Skip, the divorce decree required him to spend weekends with his father. One weekend, Skip, who dreaded staying with his father’s new family, called Sally and begged to be allowed to come home. There was nothing she could do, she told him, given the court order. Skip went down to the basement and killed himself with his father’s hunting rifle.

A distraught Sally, blaming Cecil for their son’s death, sued for control of Skip’s meager estate. Cecil countersued. The Idaho courts held that, under state law, when a man and a woman both applied to be an executor, the man was automatically chosen. The courts believed the law was “rational” because giving men automatic preference saved the court system from the time and expense of adjudicating every case.

The 64-page brief questioning that law was written by Ginsburg with the cooperation of the American Civil Liberties Union legal director. She would use it and her subsequent six Supreme Court cases (she won five of them) to meet the second challenge: showing the justices how the exclusion of women from public life treated them as less-than-full citizens.

‘Akin to a grade school teacher’

In her Reed v. Reed brief, Ginsburg presented the all-male Supreme Court with a carefully crafted introductory essay on the history of women in the United States, citing sources from Caroline Bird’s “Born Female: The High Cost of Keeping Women Down”; Elizabeth Janeway’s “Man’s World, Woman’s Place: A Study in Social Mythology”; John Stuart Mill’s “The Subjection of Women”; and government statistics on women’s employment.

The eclectic brief, in addition to citing legal treatises and precedents, also drew on biology and philosophy. Gender, it explained, was as mistaken and unconstitutional a basis for laws as race was. “Designation of sex as a suspect classification is overdue,” the brief declared.

“As an advocate in gender discrimination cases in the ’70s,” Ginsburg later said, “I thought of myself as akin to a grade school teacher.”

That was, she said, because “most of the men in the courts at that time didn’t associate discrimination in its unpleasant sense with the way women were treated. They thought of themselves as good husbands and good fathers. They genuinely believed that women had the best of all possible worlds. Women could work if they wanted to; they could stay home if they wanted to. […] The challenge was to educate the men on the bench.”

The Supreme Court wasn’t willing to go so far as to give up the rational relation test. It reversed the Idaho courts’ decision and, in doing so, tightened the test. States could not “treat different classes of persons in different ways,” it declared. A classification had to be “reasonable, not arbitrary, and must rest upon some ground of difference having a fair and substantial relation to the object of the legislation.”

If the object of the law here was to ensure the best possible person as executor, then it was not rational to assume all men were better suited than women — some of whom, Chief Justice Warren Burger pointed out for a unanimous court, were widows already acting as executors.

Ginsburg was undeterred by the court’s refusal to adopt the suspect classification doctrine. “Real change, enduring change,” she often said, “happens one step at a time.”

The whole point of arguing for a more stringent test, anyway, was to lay the groundwork, to plant a seed in the justices’ minds in the hope it would sprout when they were presented with other cases later on. A step-by-step strategy would take the justices along the path she wanted them to follow.

Another step involved a case brought on behalf of a man.

When Paula Polatschek and Stephen Wiesenfeld married in 1970, she was working as a math teacher, and he was a computer consultant. That year, Paula earned $9,808; Stephen, $3,100. Paula continued to be the primary breadwinner during their marriage, paying into the Social Security system. By 1971, the Wiesenfelds were ready to begin a family, and Paula became pregnant.

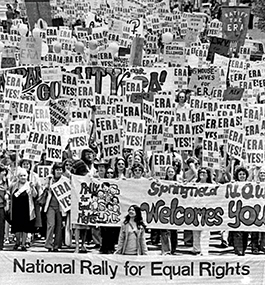

Associated Press

RALLYING POINT: Thousands of people march outside the Illinois State Capitol in May 1976, urging the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment.

page 2 of 2

On June 5, 1972, Paula died during childbirth. A grieving Stephen was determined to raise his infant son, Jason Paul, by himself. He knew he would not be able to spend sufficient time with Jason while working full time, so he applied for Social Security child care benefits.

He learned, however, that under Social Security laws he was ineligible for the “child in care” payments that went to a widow in his situation. The law provided a benefit only for a “mother [who] has in her care a child of [an insured] individual,” not for a father. Stephen could collect only half the amount that would have been paid to a similarly situated woman survivor of a male wage earner.

Ginsburg thought Stephen’s situation presented the perfect example of the unfairness wreaked by sex-specific laws.

By now, she was no longer at Rutgers. In 1972, the ACLU created the Women’s Rights Project, and Ginsburg was asked to head it. Columbia University’s law school also wanted her (perhaps at least in part because it had come to recognize it really ought to have women on its faculty).

Ginsburg agreed to work half time at the ACLU and half time at Columbia. She created a course on equal rights advocacy at Columbia and turned some of the work on the Wiesenfeld case over to her students. This became a hallmark of her advocacy: involving law school students, from other universities as well as Columbia, as partners in her litigation. It gave her the assistance the underfunded Women’s Rights Project could not provide — and trained the next generation of litigators.

Ginsburg began her Wiesenfeld presentation at the Supreme Court by speaking at length about the family. She believed the justices needed to see the real people and potential real-world consequences involved in gender discrimination cases. With Stephen sitting at the counsel table — she wanted the justices to see a man hurt by gender classifications — she described the way all three Wiesenfelds were discriminated against by the law.

Here’s part of her opening statement, from the court transcript:

MRS. GINSBURG: In 1972, Paula died giving birth to her son, Jason Paul, leaving the child’s father, Stephen Wiesenfeld, with sole responsibility for the care of Jason Paul.

For the eight months immediately following his wife’s death and all but a seven-month period thereafter, Stephen Wiesenfeld did not engage in substantial gainful employment. Instead, he devoted himself to the care of the infant, Jason Paul. […]

[T]here could not be a clearer case than this one of the double-edged sword in operation of differential treatment accorded similarly situated persons based grossly and solely on gender.

Paula Wiesenfeld, in fact the principal wage earner, is treated as though her years of work were of only secondary value to her family. Stephen Wiesenfeld, in fact the nurturing parent, is treated as though he did not perform that function. And Jason Paul, a motherless infant with a father able and willing to provide care for him personally, is treated as an infant not entitled to the personal care of his sole surviving parent.

This was a glaring instance of gender discrimination, she argued. And when the court announced its unanimous decision on March 19, 1975, it was clear the justices also thought the regulation unconstitutional — although they couldn’t agree on the reason. Justice William Brennan Jr., writing for the court, described the case as involving women’s rights; Justice Lewis Powell, joined by Chief Justice Burger, as a matter of fairness to men; Justice William Rehnquist, as a victory for children’s rights. Among them, as Ginsburg would comment, they “covered all the bases.”

Uniquely right

By the end of 1979, Ginsburg had become a one-woman whirlwind litigating for gender equality. She had participated in writing the main brief for nine cases decided by the Supreme Court, argued six of those, participated in amicus (friend of the court) briefs in another 15 Supreme Court cases, worked on 11 major cases the court chose not to take, and helped draft other memoranda and petitions.

“Think of any Supreme Court decision on women’s rights in the 1970s,” the constitutional scholar Kenneth Karst wrote, “and you can be sure that Ruth Bader Ginsburg was there.”

The court was still judging gender discrimination claims on the basis of an expanded rational relation test when President Jimmy Carter appointed Ginsburg to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1980. But she had taught the justices there was nothing rational about sex discrimination. The Constitution, in effect, read quite differently than it had when she began litigating.

She had not only been in the right place at the right time, she proved to be the uniquely right person to make the right arguments to change the status of women under American law.

President Bill Clinton appointed Ginsburg to the Supreme Court in 1993. Three years later, she wrote the court’s majority opinion in U.S. v. Virginia, in which the federal government challenged the men-only admissions policy at the Virginia Military Institute, a state-sponsored school. The court still wasn’t quite ready to adopt the suspect classification test, but Ginsburg was able to draw on the lessons she had provided for the justices and the precedents she had established in the 1970s to push the court farther down the path.

“The heightened review standard our precedent establishes does not make sex a proscribed classification,” her opinion acknowledged, referring again to the test used for cases alleging racial discrimination. And yet, she added, “‘inherent differences’ between men and women [...] remain cause for celebration, but not for denigration of the members of either sex or for artificial constraints on an individual’s opportunity.” A classification based on gender “may not be used [...] to create or perpetuate the legal, social, and economic inferiority of women.”

Ginsburg didn’t take any reproductive freedom cases to the Supreme Court during her years at the ACLU. The Ford Foundation was the Women’s Rights Project’s primary funder, and it refused to donate to any entity that brought such cases, so the ACLU created a separate division to litigate them.

There is, however, ample evidence of her views on a woman’s constitutional right to choose. In 1993, she told the congressional committee considering her nomination to the Supreme Court that reproductive freedom was “central to a woman’s life, to her dignity. It’s a decision that she must make for herself. And when government controls that decision for her, she’s being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for her own choices.”

Ginsburg died in 2020, two years before the Supreme Court eviscerated the constitutional right to abortion. What the woman who did more than anyone else to make gender equality a feature of the U.S. Constitution would have thought about that ruling is nonetheless very clear.

Philippa Strum is a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, former director of the center’s Division of United States Studies, and the Broeklundian Professor of Political Science Emerita at the City University of New York. Her most recent book is “On Account of Sex: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Making of Gender Equality Law” (University Press of Kansas, 2022).