Turning Points

I Am Going To Be in This Show

Giselle Potter

by Ray Wills, GSAS MFA’85

Sometimes, you walk down a street, turn a corner, and find yourself face to face with the messenger of your destiny.

I was an actor, impatiently navigating my way through the crowds in Times Square, going to the credit union to deposit my unemployment check, when I ran into another actor I knew.

He greeted me warmly: “So, what are you up to?”

(“What are you up to?” is the professional actor’s code for Are you working? and, if you are not, you are allowed to use phrases like “I’m between gigs right now” or “I’m auditioning a lot,” which at least saves face.)

“Well, right now I’m just auditioning a lot,” I said. (I had one audition three weeks ago.)

“Yeah, it’s kind of slow,” he said. (Keep cashing those unemployment checks.)

“I just did a reading, though.” (Two months ago.)

“Oh, great!” (For no money, right?)

“Yeah, it was pretty good — nice role.” (It sucked, and I mostly read stage directions.)

Readings are a common activity for actors. You don’t get paid a lot, usually bupkis (Yiddish for “nothing,” but it sounds better). Writers and directors and producers need to hear a script read out loud by performers to see if it works.

Readings are a way for actors to mark their territory. If you are wonderful, writers and directors and producers will feel that no one else can possibly do the part, unless you are reading the starring role, in which case you are probably a placeholder, and as soon as a Big Star wants to play it on Broadway, you get bupkis.

When you run into another actor on the street and you are doing a reading of a really good play, nothing feels better than talking about it as long as you fulfill the obligation of shrugging it off as if it’s no big deal.

“I’m doing a reading of this new show,” my actor acquaintance said. (Please ask me what it is.)

“What is it?” I asked. (Probably for Broadway, right?)

“It’s a musical version of Mel Brooks’ ‘The Producers.’” (It’s going to be a hit!)

I went blank for a moment with the usual queasy envy actors feel when they haven’t been invited to a party. Then he said Susan Stroman was directing. That caught my attention.

I’d worked with Stroman a few years earlier when she choreographed the Broadway musical “Big,” based on the Tom Hanks film. I played a bunch of character parts in addition to understudying one of the leading roles. It wasn’t a huge hit, but it was a great experience.

Stro is brilliant, she’s demanding, and she’s fun. I could see her directing the hell out of this show. I had never met Mel Brooks beyond seeing him and his films on a movie screen, but what has he ever done that wasn’t successful? This sounded like a job an actor could only dream of.

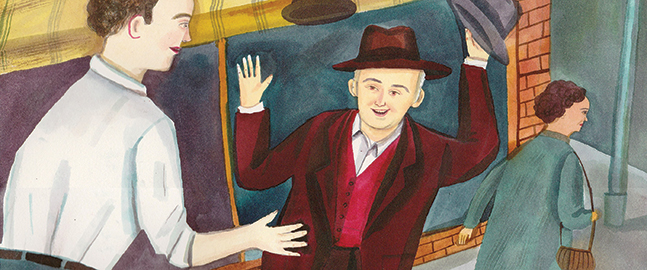

As the guy talked about how funny the script was, I remembered the film version of “The Producers” had all kinds of character men in it. I had a vision of myself on a stage wearing a bunch of different hats, and suddenly it was as if a strobe light went off in my brain, and I thought, with absolute clarity, I am going to be in this show.

Sometimes, a dream really does come true.

In April 2001, “The Producers” opened on Broadway. The following June, the show won the most Tony Awards in Broadway history. Ray Wills played several character roles in that original production, which sold out every performance for two years, and went on for Nathan Lane as the understudy for the Max Bialystock role 36 times. Wills is an instructor of interpersonal communications at the University of Kansas School of Medicine. (This essay is adapted from his 2022 book, “Being Max: A Short Memoir About a Long Day in the Life of a Broadway Understudy.”)