Tableaux for a Troubled World

Assistant professor Sheida Soleimani’s photo collages ask us to consider the suffering of oppressed people — and our part in it.

Jörg Meyer

Sheida Soleimani

by Lawrence Goodman

Growing up in Ohio, Sheida Soleimani, an assistant professor of fine arts at Brandeis, listened to her mother’s bedtime stories, drawn from Persian folklore, filled with evil snakes and scarab-like insects.

She also heard true stories of horror about her mother’s earlier life as a nurse and a political dissident in Iran. In Shiraz in the 1970s, Soleimani’s mother treated lepers and injured villagers at a Kurdish field hospital. She saved stillborn babies and fetuses from being thrown into the trash, burying them in large jars beneath her family’s sour orange tree.

Arrested for her political activities, Soleimani’s mother was thrown into solitary confinement, where she listened to fellow prisoners whispering through the walls. She told her young daughter about one prison detainee who breastfed for as long as she could, because under Iranian law she could not be put to death if she was nursing. When the child turned 3 and stopped nursing, the woman was executed.

“My parents’ generation doesn’t really believe in therapy,” Soleimani says. “Culturally, it’s not widely accepted. So I became my mother’s child therapist.”

As the years went by, her mother’s Iran stories became a rich source of creative material for Soleimani, who is a multimedia tableau artist. She stages and photographs scenes filled with stuffed fabric shapes; backgrounds fashioned from brightly colored paper; photos and drawings; digital images; papier mâché constructions; and, sometimes, live animals and real people. At only 32, Soleimani has exhibited her work in New York, Italy, Brussels, and London, and it’s been featured in The New York Times, Harper’s Bazaar, and Artforum.

Her collages are alternately satirical, grotesque, horrifying, and beautiful. Until now, they have mostly explored Middle Eastern geopolitics, from Iran’s human rights abuses to the excesses of American oil policy. In her more recent work, she’s begun to focus on her parents, who fled persecution in Iran in the 1980s.

In late August, while Soleimani’s mother was visiting her daughter’s Victorian home in Providence, Rhode Island, Soleimani asked her to pose for a photo for a collage. Her mother sat on the floor and hugged her knees, her long white hair flowing over one shoulder. A checkerboard pattern of light blue and yellow squares was affixed to the wall behind her. Crudely drawn black lines on the floor and wall outlined the image of a small room with a narrow rectangular barred window.

The finished tableau, far from dismal, imagines her mother’s prison cell as a fantasia of her visions of freedom, says Soleimani. Cut-up photographs placed on the wall depict a passage through the Zagros Mountains that leads to Turkey. Soleimani’s mother looks up at a ladder barely tall enough to reach the room’s window, her only hope for escape.

The series this tableau is part of is called “Ghostwriter.” Soleimani chose the title because she feels her mother and father want her to tell their personal stories. But the title is not without irony: Soleimani is retelling her parents’ stories on her own terms, using the photographic techniques and mixed-media materials she’s been experimenting with for a decade.

Dystopian dress-up

When she was a kid in Cincinnati, Soleimani didn’t have many friends. Hers was the only family from Southwest Asia in the area, which was still dotted with cornfields and grain silos. Her parents spoke Farsi at home; Soleimani didn’t learn English until she went to school. When she told other kids her mother had been imprisoned, they thought that meant her mom was a criminal.

After 9/11, Soleimani was fearful of her neighbors’ anger. As Middle Easterners, her family was seen as somehow responsible for the attack. After all, the distinction between “Iraq” and “Iran” was a mere letter. The family’s home was defaced with toilet paper. Someone took a baseball bat to their mailbox. Even after Soleimani’s father moved it away from the street, the vandals struck twice more. Finally, he moved the mailbox so close to the house no one dared damage it again.

Soleimani’s father told her she should tell her classmates he played backgammon with Saddam Hussein — an early lesson in the power of humor and satire to combat prejudice, she says.

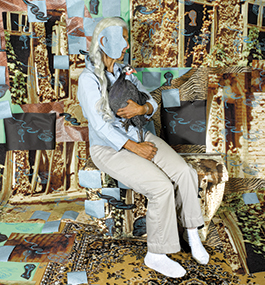

“Noon-o-namak (Bread and Salt),” 2021.

page 2 of 4

By high school, Soleimani had found a few kids to hang out with. They were, she says, the ones “everybody else made fun of, so it was a natural fit.” They took pictures of themselves and posted them on the early social-media site MySpace. In her first attempts at photographing tableaux, Soleimani posed her friends, wearing vintage clothing from thrift stores, in cemeteries and inside abandoned grain silos and industrial buildings. “Everybody thought I was weird, so I decided I’m going to be extra-weird,” she says. “It was my dystopian version of dress-up.”

Though she had intended to become a scientist or a doctor, she found herself using her Type 1 diabetes as an excuse to get out of math class. The school nurse told her she couldn’t keep coming to her office for juice, a moment that led to a reckoning. “I’m having fun doing photography,” Soleimani remembers thinking. “Why not make it a career?”

In 2010, during her sophomore year at the University of Cincinnati, Soleimani met visual artist Yamini Nayar, who creates life-size photographs of sculptures made from found materials. Soleimani marveled at how Nayar assembled disparate shapes and fragments to suggest gorgeous architectural structures. The result was fluid and open-ended enough to invite viewers to create their own story, yet not so loosely defined that the image was incoherent. Soleimani and Nayar stayed in touch, and Nayar became a mentor.

Soleimani began pursuing an MFA at Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art in 2013. Increasingly, her work focused on human rights violations in Iran, inspired by her parents’ story.

The representation of suffering — of political prisoners, of women in the Middle East, of entire nations victimized by American colonialism — remains a central preoccupation of her tableaux. Her works demand viewers acknowledge their biases, preconceptions, and prejudices. They force viewers to ask themselves whether their interest in witnessing the oppression and misery of others is an addiction to what she calls “the pornography of pain.”

Soleimani’s dining-room walls are lined with political posters, a decoration scheme influenced by her father, who likes to talk politics over dinner. One antiwar poster shows victims of the 1968 My Lai Massacre — dead and partly naked women and babies — lying on a dirt road. Another features an image of Ronald Reagan and the Doomsday Clock, with the caption “We begin bombing in five minutes.”

They don’t exactly make for pleasant viewing, especially at mealtime, but familiarity breeds contemplation. As Soleimani grew less affected by these images, she thought about why and how they became so powerful in the first place. Why does it take depictions of horror to raise our consciousness and spur activism? Were My Lai’s victims doubly violated when a photograph of their bodies was reproduced for American consumption, even if it was for a good cause?

In “National Anthem,” Soleimani’s first major body of photomontage work, produced in 2014-15, a woman, naked except for a pink chador, lies on an Oriental rug on a beach. Is her gaze beseeching? Come-hither beckoning? Is she oppressed or liberated? Soleimani doesn’t provide any answers. All the Western viewer knows is this is not what the suffering and oppression of Middle Eastern women is supposed to look like.

In “Ghostwriter,” Soleimani hides her mother’s face with a piece of paper. It’s meant to protect her identity, but it raises larger questions about how we relate to victims of political persecution. Do we need to see faces to connect and identify with pain? If so, why?

‘A trail of breadcrumbs’

Soleimani inherited her politics from her father.

A native of Abadan, Iran, he excelled in school and decided to become a doctor. He met Soleimani’s mother in 1975 at a hospital in Shiraz, where they were both in training. Soleimani’s father actively opposed the shah but, after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, quickly grasped Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini wouldn’t be much better.

At Soleimani’s father’s hospital, doctors were ordered not to treat political-opposition members. In 1980, a political protester shot by the authorities arrived badly injured. The doctor who dared treat him was soon arrested and executed. At his memorial service, Soleimani’s father gave a fiery political speech, denouncing the government for its brutality and inhumanity. The government arrested him. When his colleagues found out, they threatened to strike, and Soleimani’s father was released with a warning.

“Khooroos (Rooster) Named Manoocher,” 2021.

page 3 of 4

Despite the danger, he remained a political activist. A few months later, he was at the home of Soleimani’s mother’s family when the military came to arrest him. Before the soldiers were let inside the house, he managed to hide in the rice cellar. The soldiers searched but didn’t find him.

For the next three years, Soleimani’s father lived in hiding, changing apartments and supporting the family by announcing the time of death of individuals brought to a cemetery for burial, to confirm they were indeed dead. Eventually, he saved enough money to hire smugglers to take him by horseback through the Zagros Mountains to Turkey. After several months, Soleimani’s mother followed by the same route, but she was captured at the border. She successfully fled to the United States three years later.

Soleimani’s father arrived in the U.S. in 1983, completing a residency in New Haven, Connecticut, and eventually working as a nephrologist at the University of Cincinnati. His politics, his daughter says, remained “Marxist-adjacent.” He believed in government health care, a strong social safety net, and state-owned industry. At age 70, he remains a fierce critic of Middle Eastern governments — especially Iran’s — for their corruption, greed, and human rights abuses.

In her “Ghostwriter” series, Soleimani tells her father’s story as well as her mother’s. In one photo, she re-creates the rice cellar where he hid from the Iranian authorities. Bags of rice are scattered on the floor. Pictures of her mother’s family’s house are tacked onto the wall. At the center of the montage is a 15-foot snake made from brown- and tan-patterned fabric stuffed with polyester fiberfill. Underneath the snake lies Soleimani’s father; only his lower legs and bare feet are visible. Dozens of drawings of scarab-like insects fill the background. They’re balesh a maar, Farsi for “snake’s-pillow bug.” They feature prominently in the Persian folktales Soleimani’s mother used to tell. Snakes are said to use them as pillows.

Soleimani says the symbols she uses in her work function as “a trail of breadcrumbs” the viewer must follow to construct a story. In this case, the snake represents the Iranian government, crushing her father. It’s a bit of an inside reference, too: Her father was genuinely afraid of being bitten by a snake while he was down in the rice cellar.

Around 2017, Soleimani began exploring political relationships between the Middle East and the West in a series of works about the global oil industry she titled “Medium of Exchange.” In one image, Henry Kissinger is down on bended knee, offering an engagement ring to an Angolan oil minister. With an oversized head and a hand drenched in oil, Kissinger is topless except for a suit vest and small pieces of fabric covering his enlarged breasts.

Another photograph shows Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, the architects of the Iraq War, holding hands, as if they’re going steady. Rumsfeld sits cross-legged on an oil drum; Cheney wears nothing but a towel imprinted with a $100 bill. Cutout images of billowing explosions cover the wall behind them.

Laden with irony, “Medium of Exchange” mixes gender-bending montages, satire, and cutting political commentary. Shot with a Mamiya 645 camera, often used in commercial photography, the images have a glossy glow, as though they’re advertising America’s warmongering and imperialism.

“I make photographs for a world in crisis,” Soleimani said in a 2021 interview. “Crisis demands new aesthetic forms, alternate genres, and heightened theatricality — in modes like humor and grotesque — to get our message across.”

You can’t go home again

A licensed wildlife rehabilitator, Soleimani stands in an aviary in her front yard in Providence, with one finger down the throat of a crow, another finger gently caressing the bird’s neck. The crow, named Zephyr, clearly enjoys this. “She’s like my kid,” Soleimani says.

The aviary, a wire mesh structure about the size of a shed and covered with bamboo strips so it looks less like a cage, also houses two other crows: Zero and another crow Soleimani won’t name because it will soon be released back into the wild and she doesn’t want to grow too attached. Soleimani’s partner, Jonathan Schroeder, a visiting assistant professor of American studies and English at Brandeis, arrives with bird food, a mash of dead fish, crickets, and mice. The birds caw wildly with excitement.

Soleimani’s house abuts a small cemetery. The location, she points out, means there are fewer neighbors to complain about the bird noise. She says she also finds the graveyard “healing.” A sign on the front of her house reads, “The Congress of the Birds.” It’s a reference to a 12th-century Persian poem about the coming together of all the world’s birds in search of a new leader. It also helps people find her home: The state of Rhode Island lists her address as a place where people can bring injured, sick, or poisoned birds.

During the spring and summer, the high season for drop-offs, she may have more than 50 animals in her basement “wildlife clinic,” typically robins, blue jays, owls, songbirds, pigeons, the occasional hawk, and assorted fowl, each bird housed in its own mesh enclosure. In addition, there’s a hutch she calls the “chicken palace,” which currently holds five ducks, two partridges, nine chickens, a rooster, and a guinea fowl.

“What a Revolutionary Must Know,” 2022.

page 4 of 4

Soleimani learned about wildlife care from her mother. Unable to practice nursing when she arrived in the U.S. in 1986, her mother used animal rescue as an outlet for her nurturing impulses. “It was her mission to find roadkill that wasn’t dead yet,” says Soleimani, who had rabbits, cardinals, woodpeckers, and bats as pets. She remembers sleeping with a raccoon, who liked to nestle in her hair, for several weeks when she was 5.

In college, Soleimani was nicknamed Bird Girl after she converted her apartment’s bathroom into a bird hospital. Mostly, people brought her chimney swifts, who live a precarious existence. When these cave dwellers from Peru migrate north, they roost by digging their needle-feathered tails into the lining of chimneys. Sometimes, they fall off and are burned in fireplaces. “I watch these birds go from being near death to learning to fly again and returning to the wild,” Soleimani says. “It’s a lot of hard work, but it’s really satisfying.”

For many years, Soleimani thought of her wildlife rehabilitation as separate from her art. The “Ghostwriter” series has helped her bring her love of the natural world into her work.

In one 2021 collage titled “Noon-o-namak” (“Bread and Salt” in Farsi), her mother sits atop a bench, clutching a live guinea fowl that Soleimani nursed back to health. The background shows pictures of her mother’s home in Iran. It’s a healing, restorative photograph: her mother returned to her childhood and to nature.

But the image’s fragmented construction, with the scraps of paper and photos from her past not quite fitting together, acknowledges that Soleimani’s mother can never really go back again. The montage captures the plight of all political refugees, who yearn for a past forever destroyed by violence and trauma.

Soleimani says her mission is “helping the world.” Her parents’ stories are helping her figure out how to do that.