In Black Ink, Love May Still Shine Bright

Brandeis' new poet in residence turns isolation into humor and communion.

Mike Lovett

Poet in residence Chen Chen

by Heather Salerno

Doctoral student Chen Chen was preparing for class at Texas Tech University as usual one morning when his cellphone began to chirp with Twitter notifications and news alerts. A quick glance told him something big had just happened. The long list for the 2017 National Book Award for Poetry had been released, and he was among the 10 nominees.

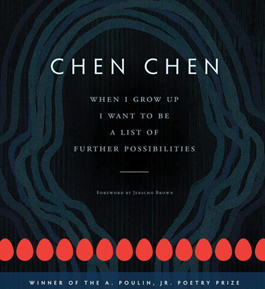

Selected for his debut collection, “When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities,” Chen was praised by the judges for exploring his identity as a young, gay Chinese-American “with unending curiosity and humor.” Chen was stunned by the announcement. He never expected to receive such recognition for his first book.

“It didn’t seem real to me at first,” he says. “It felt like they were talking about something that had happened to someone else.”

The collection went on to win the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry and was named a Stonewall Honor Book in Literature and a Lambda Literary Award finalist. Chen was featured everywhere from NPR, to The New York Times Magazine, to Buzzfeed. Poets & Writers magazine named him one of “Ten Poets Who Will Change the World.”

This fall, the 29-year-old became the Jacob Ziskind Poet in Residence at Brandeis, kicking off his two-year post by teaching an Introduction to Creative Writing course. “I always tell my students that one of the most important tasks of being a writer is to pay attention to what’s going on around you,” he says. “Inspiration can come from anywhere.”

Much of “When I Grow Up” — the book began as Chen’s MFA thesis at Syracuse University, which he attended after receiving a bachelor’s from Hampshire College — draws from challenges the poet faced growing up. Born in Xiamen, China, Chen moved to America with his family when he was 3 so his father could pursue an advanced degree in religion at Texas Christian University.

A few years later, his dad earned a scholarship to UMass Amherst, where Chen’s family lived in campus housing near other Chinese immigrant families. “There was this great little community that formed there, so I had a lot of friends who were in a similar situation,” he says. “They made me feel less lonely and less isolated.”

That changed by middle school — many of Chen’s friends had moved away, and he was questioning his sexual orientation. “It was an incredibly confusing time for me,” he says.

Writing was one thing that helped him get through. Robert Frost was an early fascination — “the rhythm of those poems was spellbinding and hypnotic to me,” Chen says. He began penning his own verses as a way to escape. “When I felt like I couldn’t talk at home about something that was going on in my life, I turned to poetry as an outlet.”

page 2 of 2

A pivotal moment came at 13 when his mother confronted him about his sexuality after overhearing a phone conversation he had with a friend. He hesitantly came out to his parents, who disapproved. The rift was devastating; he’d always been extremely close to his mother. It’s a complicated relationship, one he mentions often in his poetry. In “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential,” he writes: “I am not the heterosexual neat freak my mother raised me to be. / I am a gay sipper, & my mother has placed what’s left of her hope on my brothers.”

Though Chen often tackles tough topics, his wit shines through. Publishers Weekly wrote that he “balances the politics surrounding shame and desire with hearty doses of joy, humor and whimsy.” The final poem in Chen’s book, “Poplar Street,” in which he relates a random chat with a stranger, reveals his vulnerability, with a comic’s touch: “Maybe, beyond briefcases, we have some things / in common. I like jelly beans. I’m afraid of death. I’m afraid / of farting, even around people I love. Do you think your mother / loves you when you fart? Does your mother love you / all the time? Have you ever doubted?”

|

|

Sidebar |

|

Early on, Chen thought poets always had to be serious to be taken seriously. But he’s not like that in real life. For instance, Mr. Rupert Giles, the beloved pug he shares with partner Jeff Gilbert, is named after a character on “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” one of Chen’s favorite TV shows. In graduate school, influenced by poets like A.R. Ammons, Chen realized humor might make his work more realistic and relatable.

“If I bring in more of the way I talk with my friends and people I’m close to, I can create this more intimate and lively voice in my poetry,” he says. Plus, he adds, “I don’t think I’d want to write draft after draft exploring these difficult subjects if there wasn’t something else going on that was a little bit playful.”

Chen encourages his Brandeis students to do their own experimenting as writers. Elizabeth Bradfield, the associate professor of the practice of English who headed the poet-in-residence search committee, says she and her colleagues felt Chen, a writer from traditionally underrepresented groups who had won acclaim for his first book, would be a wonderful on-campus role model. But Bradfield says they were additionally impressed by Chen’s “grounded, engaged and generous” teaching philosophy. “We loved his dedication to helping students find their own poetic path,” she says.

Along with his duties at Brandeis, Chen promotes the work of other poets as co-editor of the online journal Underblong. He’s also finishing his PhD in English and creative writing at Texas Tech. His dissertation is likely to become his second volume of poetry.

With a schedule packed with readings, workshops and appearances around the country, he often meets readers who feel a personal connection to his writing. At the Brooklyn Book Festival in September, a young Asian-American woman told Chen she wanted to come out to her family but the decision has been a difficult one. His poems, she said, made her feel less alone.

“I was talking about these painful experiences of not belonging,” Chen says, “and she told me how that was so important for her to hear. Hearing her story, I thought, ‘Wow, it’s amazing that poetry can have that kind of power.’”

Heather Salerno is a freelance writer who lives in the Greater New York City area.