“Savings Bank Life Insurance,

Wage Earners’ Life Insurance”

by Louis D. Brandeis

Transcript

[Page] 3

of insurance so purchased; whereas in ordinary life insurance the variation is in the amount of premium.

- (b) That the premium is payable weekly; whereas in ordinary life insurance the premium is payable annually, semi-annually, or quarterly.

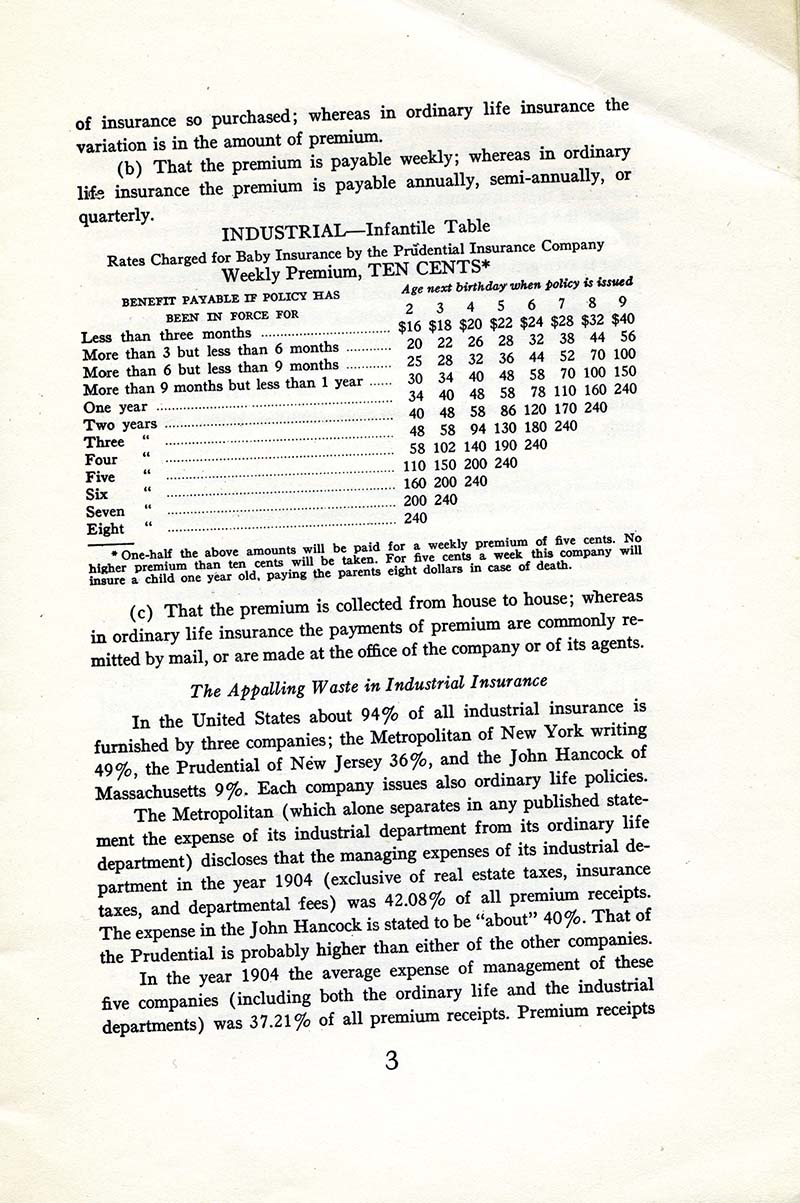

INDUSTRIAL--Infantile Table

Rates Charged for Baby Insurance by the Prudential Insurance Company

Weekly Premium, TEN CENTS

| Benefit payable if policy

has been in place for | Age next birthday when policy is issued | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Less than three months | $16 | $18 | $20 | $22 | $24 | $28 | $32 | $40 |

| More than 3 but less than 6 months | 20 | 22 | 26 | 28 | 32 | 38 | 44 | 56 |

| More than 6 but less than 9 months | 25 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 44 | 52 | 70 | 100 |

| More than 9 months but less than 1 year | 30 | 34 | 40 | 48 | 58 | 70 | 100 | 150 |

| One year | 34 | 40 | 48 | 58 | 78 | 110 | 160 | 240 |

| Two years | 40 | 48 | 58 | 86 | 120 | 170 | 240 | |

| Three years | 48 | 58 | 94 | 130 | 180 | 240 | ||

| Four years | 58 | 102 | 140 | 190 | 240 | |||

| Five years | 110 | 150 | 200 | 240 | ||||

| Six years | 160 | 200 | 240 | |||||

| Seven years | 200 | 240 | ||||||

| Eight years | 240 | |||||||

*One-half the above amounts will be paid for a weekly premium of five cents. No higher premium than ten cents will be taken. For five cents a week this company will insure a child one year old, paying the parents eight dollars in case of death.

- (c) That the premium is collected from house to house ; whereas in ordinary life insurance the payments of premium are commonly remitted by mail, or are made at the office of the company or of its agents.

The Appalling Waste in Industrial Insurance

In the United States about 94% of all industrial insurance is furnished by three companies; the Metropolitan of New York writing 49%, the Prudential of New Jersey 36%, and the John Hancock of Massachusetts 9%. Each company issues also ordinary life policies.

The Metropolitan (which alone separates in any published statement the expense of its industrial department from its industrial department in the year 1904 (exclusive of real estate taxes, insurance taxes, and departmental fees) was 42.08% of all premium receipts. The expense in the John Hancock is stated to be “about” 40%. That of the Prudential is probably higher than either of the other companies.

In the year 1904 the average expense of management of these five companies (including both the ordinary life and the industrial departments) was 37.21% of all premium receipts. Premium receipts

[Page] 11

compelled to submit to a system which requires such great and largely useless sacrifices in the supposed interest of a small minority.

The thrifty working man, like people of larger means, should have the opportunity of obtaining life insurance at more nearly its necessary cost.

The Remedy

The sacrifice incident to the present industrial insurance system can be avoided only by providing an institution for insurance which will recognize that its function is not to induce working people to take insurance regardless of whether they really want it or can afford to carry it, but rather to supply insurance upon proper terms to those who do want it and can carry it -- an institution which will recognize that the best method of increasing the demand for life insurance is not eloquent persistent persuasion, but, as in the case of other necessaries of life, is to furnish a good article at a low price.

The Savings Bank the Best Remedy

Massachusetts in its 189 savings banks, and the other states with savings banks similarly conducted, have institutions which, with a slight enlargement of their powers, can at a minimum of expense fill the great need of life insurance for working men.

The only proper elements of the industrial insurance business not common to the savings bank business are simple and can be supplied at a minimum of expense in connection with our existing savings banks. They are:

- (a) Fixing the terms on which insurance shall be given.

- (b) The initial medical examination.

- (c) Verifying the proof of death.

The last involves an inquiry similar in character to that now performed by the clerks of savings banks in the identification of depositors.

The second is the work of a physician, who is available at no greater expense to the savings bank than to the insurance company.

The first is the work of an insurance actuary, who would be equally available to the savings banks, as he is to insurance companies, if the latter undertook the insurance business. And the present cost of actuarial service can be greatly reduced--first, by limiting the forms of insurance to two or three standard forms of simple policies--uniform throughout the state--and, secondly, by providing for the appointment of a state actuary, who in connection with the insurance commissioner, shall serve all the savings insurance banks. The work of such an

[Page] 12

actuary is, indeed, now necessarily performed in large part in each state by the insurance department, as an incident of supervising life insurance companies.

The savings banks could thus enter upon the insurance business under circumstances singularly conducive to extending to the working man the blessing of safe life insurance at a low cost, because:

First: The insurance department of savings banks would be managed by experienced trustees and officers who had been trained to recognize that the business of investing the savings of persons of small means is a quasi-public trust which should be conducted as a beneficent and not as a selfish money-making institution.

Second: The insurance department of savings banks would be managed by trustees and officers who in their administration of the savings of persons of small means had already been trained to the practice of the strictest economy.

Third: The insurance business of the savings banks, although kept entirely distinct as a matter of investment and accounting, would be conducted with the same plant and the same officials, without any large -increase of clerical force or incidental expense, except such as would be required if the bank's deposits were increased. Until the insurance business attained considerable dimensions, probably the addition of even a single clerk might not be necessary. The business of life insurance could thus be established as an adjunct of a savings bank without incurring that heavy expense which has ordinarily proved such a burden in the establishment of a new insurance company.

If the individual risks were limited at first to, say, $150 on a single life, the business could be begun safely on a purely mutual basis as soon as a few hundred lives were insured, or earlier if a guaranty fund were provided. As the business increased, the limit of single risks could be correspondingly increased, but should probably not exceed $500.

Fourth: The insurance department of savings banks would open with an extensive and potent good-will, and with the most favorable conditions for teaching, at slight expense, the value of life insurance. The safety of the institution would be unquestioned. For instance, in Massachusetts, the holders of the 1,829,487 savings bank accounts, a number equal to three-fifths of the whole population of the state, would at once become potential policyholders; and a small amount of advertising would soon suffice to secure a reasonably large business without solicitors.

[Page] 13

Fifth: With an insurance clientele composed largely of thrifty savings bank depositors, house-to-house collection of premiums could be dispensed with. The more economical monthly payments of premiums could also probably be substituted for weekly payments.

Sixth: A small initiation fee could be charged, as in assessment and fraternal associations, to cover necessary initial expenses of medical examination and issue of policy. This would serve both as a deterrent to the insured against allowing policies to lapse and a protection to persisting policyholders from unjust burdens which the lapse of policies casts upon them.

Seventh: The safety of savings banks would, of course, be in no way imperiled by extending their functions to life insurance. Life insurance rests upon substantial certainty, differing in this respect radically from fire, accident, and other kinds of insurance. As Insurance Commissioner Host, of Wisconsin, said in a recent address:

“If we take a number of thousand persons of different ages, nothing is more certain in nature than that their natural deaths will occur in a series not differing very widely from that of other thousands of persons under similar circumstances.

The practical experience of this theory has given to the world the mortality tables upon which life insurance premiums are ascertained and the reserves for the future needs calculated.

No life insurance company has ever failed which complied strictly with the law governing the calculation, maintenance, and investment of the legal reserve .... ”

The causes of failure in life insurance companies since Elizur Wright established the science have been excessive expense, unsound investment, or rapacious or dishonest management. To the risk of these abuses all financial institutions are necessarily subject, but they are evils from which our savings banks have been remarkably free. This practical freedom of our savings banks from these evils affords a strong reason for utilizing them to supply the kindred service of life insurance.

The theoretical risk of a mortality loss in a single institution greater than that provided for in the insurance reserve could be absolutely guarded against, however, by providing a general guaranty fund, to which all savings insurance banks within a state would make small pro-rata contributions-a provision similar to that prevailing in other

[Page] 14

countries, where all banks of issue contribute to a common fund which guarantees all outstanding bank notes.

Eighth: In other respects, also, cooperation between the several savings insurance banks within a state would doubtless, under appropriate legislation, be adopted; for instance, by providing that each institution could act as an agent for the others to receive and forward premium payments.

Ninth: The law authorizing the establishment of an insurance department in connection with savings banks should, obviously, be permissive merely. No savings bank should be required to extend its functions to industrial insurance until a majority of its trustees are convinced of the wisdom of so doing.

The savings banks are not, however, the only existing class of financial institutions which could be utilized for the purpose of supplying, at a low expense rate, insurance in small amounts under a system requiring frequent premium payments. Cooperative banks, as operated in Massachusetts and in some other states, would under appropriate regulation, be admirably adapted to supply a part of the required service. The excellent record of these institutions in Massachusetts presents a most encouraging exhibit of the achievements of financial democracy when applied to small units, and when operating under a wise system of supervision.

Public attention having at last been directed to this subject, our working men will not long submit to the needless sacrifice of their hard-earned savings, described in the following judgment of the “Armstrong Committee” on the methods of the Metropolitan Company:

“In fine, the Industrial Department furnishes insurance at twice the normal cost to those least able to pay for it; a large proportion, if not the greater number of the insured, permitting their policies to lapse, receive no money return for their payments. Success is made possible by thorough organization on a large scale and by the employment of an army of underpaid solicitors and clerks; and from margins small in individual cases, but large in the aggregate, enormous profits have been realized upon an insignificant investment.”

If an opportunity for cheaper life insurance is afforded by means of an extension of the functions of our savings banks, the present industrial insurance companies may be permitted to pursue their efforts.at inculcating thrift in accordance with the system which seems to them

[Page] 15

wise, and their claim that the present huge waste is inevitable will be duly tested.

But, if we fail to offer to working men some opportunity for cheaper insurance through private or quasi-private institutions, the ever-ready remedy of state insurance is certain to be resorted to soon--and there is no other sphere of business now deemed private upon which the state could so easily and justifiably enter as that of life insurance.

However great the waste in present life insurance methods, our working men will not be induced to abandon life insurance. To them, as to others, life insurance has become a prime need. It must be continued. It should be encouraged. In spite of the disastrous results of this form of savings investment, the industrial insurance business has assumed enormous proportions. On December 31, 1904, the number of industrial life policies outstanding in the three great companies (Metropolitan, Prudential, and John Hancock) was 14,731,463, as against a total of only about 5,258,255 ordinary life policies outstanding in the ninety legal reserve companies. The New York Life, with its record of 957,201 policies outstanding, had only one-eighth as many policyholders as the Metropolitan, one-sixth as many as the Prudential, and three-fifths as many as the John Hancock. In the year 1904 alone the Metropolitan, Prudential, and John Hancock wrote 3,742,209 industrial policies; that is, more than three times as many as the 90 leading level premium companies wrote of ordinary life policies during that year. In Massachusetts the predominance of industrial policies is even greater than the average. With a population of 3,000,680, there were outstanding December 31, 1904, 1,080,003 industrial policies; that is,' one for every three inhabitants, counting men, women, and children, and of ordinary life policies only 257,792 were outstanding.

The demand of working men for life insurance will continue and will grow; but the yearly tribute of the working men to Prudential stockholders of dividends equivalent to 219.78% on the capital actually paid into the company, the yearly waste of millions in lapsed policies, in fruitless solicitation, and in needless collections will cease. The question is merely whether the remedy shall be applied through properly regulated private institutions, or whether the state must itself enter upon the business of life insurance.

| CREATOR | Louis D. Brandeis |

|---|---|

| DATE | Undated |

| DESCRIPTION | Cover page, Pages 3, 11, 12-13, 14-15 |

| FORMAT | Text (Book) |

| LANGUAGE | English |

| COLLECTION | Louis Dembitz Brandeis Collection |

| BOX, SERIES | 67, II.I.a.4 |

| RIGHTS | Copyright restrictions may apply. For permission to copy or use this image, contact the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University Library |