Early Marcuse Manuscript Discovered in Brandeis Archives

Mike Lovett

by Laura Gardner, P’12

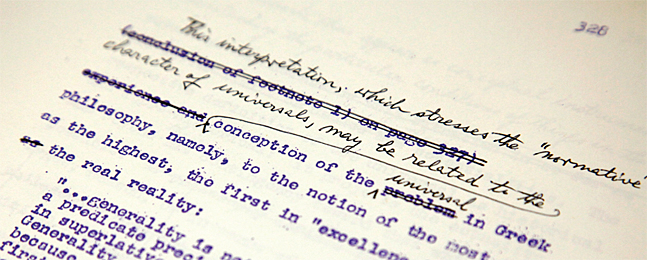

Finding a long-forgotten manuscript can be the academic equivalent of hitting the jackpot. So when an early draft of the 1964 classic “One-Dimensional Man” by legendary politics professor Herbert Marcuse was unexpectedly discovered in the Goldfarb archives last fall, librarians and scholars alike responded with giddy excitement.

Marcuse, who taught at Brandeis from 1954 to 1965, might have disdained such cheer himself. Not known for his sunny philosophical outlook, the Marxist thinker condemned capitalism and what he saw as the soul-destroying aspects of a technology-driven culture of mass entertainment and mass consumption — a phenomenon that has seemingly accelerated in the decades since “One-Dimensional Man” was published.

A dark critique of contemporary American society written in the shadow of the Cold War and the growing Vietnam conflict, “One-Dimensional Man” remains a staple of syllabuses in politics, sociology and philosophy classes. At Brandeis, sociologist Laura Miller discusses a chapter from the book in her “Culture of Consumption” class, while intellectual historian Eugene Sheppard has used sections of the book in his Near Eastern and Judaic studies class “Divided Minds.”

The early manuscript, neatly tied inside two black notebooks, was discovered by Patrick Gamsby, academic outreach librarian for the humanities, as he sifted through boxes of materials that had been stored off-site. He was in search of something Marcusian to help celebrate this year’s 50th anniversary of the publication of “One-Dimensional Man” at a Brandeis symposium planned for October — and struck gold.

“Without a doubt, this early manuscript is the best possible item I could have come across in my search for Marcuse materials here at Brandeis,” says Gamsby. “It was definitely a eureka moment for me.”

Although the manuscript’s provenance is unclear, it’s possible Marcuse gave it to Brandeis when he retired in 1965. It bears notable differences from the published work, including, according to Gamsby and others, a starker opening but a more hopeful conclusion about the future of culture.

Born and educated in Germany, Marcuse (1898-1979) fled Nazi persecution in 1934 and settled in the United States. Following stints at Columbia and Harvard, he joined Brandeis’ politics department in 1954, becoming “the most influential and widely known of the social scientists,” as founding president Abram L. Sachar wrote in “Brandeis University: A Host at Last.”

He was accused of being prolix and ponderous, offering no ready actionable remedy for social ills. Nevertheless, Marcuse deeply inspired the New Left and countless students across the country and at Brandeis, including political activist Angela Davis ’65, who became his protégée and a leading force in the radical student movement of the 1960s.

Says Sheppard, “I find it amazing that a relatively obscure Hegelian philosopher from Germany writes a book that ends up becoming a lightning rod for rebellion, student movements and the New Left, even though it’s a very dark work and advances no clear path forward.”