The Eyes (and Ears) Have It

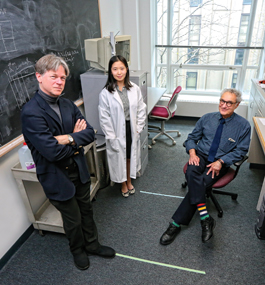

Tim Hickey ’77; Yile Sun, PhD’17; and Bob Sekuler ’60

by Lawrence Goodman

The next time you launch your favorite video game, consider this: Video games are more than what you see. What you hear matters a lot, too.

That’s the conclusion of recent research conducted by Robert Sekuler ’60, the Louis and Frances Salvage Professor of Psychology and a professor of neuroscience; Tim Hickey ’77, professor of computer science; and Yile Sun, PhD’17.

Sekuler studies how the human senses, especially sight and hearing, work with and compete with one another. “We live in a multisensory world,” he says. “How does the brain combine information from different senses? How does it decide when stimuli should and shouldn’t be combined?”

To help answer these questions, Sekuler, Hickey and Sun created a video game they call “Fish Police!!” A boat’s bow peeks out from the bottom of the screen. Above it, fish swim horizontally against a watery turquoise background. Players are shown examples of two kinds of fish. One is a “good” fish. As it swims across the screen, it changes size, or oscillates, slowly. Then a “bad” fish swims past, oscillating more rapidly.

Over the course of the five-minute game, good and bad fish appear randomly, one after the other. Players must press one button on the joystick whenever they see a good fish and another button whenever they spot a bad fish. They earn a point every time they respond correctly within two seconds.

The game also has an auditory element. While a fish swims, a tone is emitted that fluctuates in loudness, either slowly or rapidly.

Players performed best when the rate at which a fish fluctuated in size matched the rate at which the sound fluctuated in loudness.

When the cues were mismatched — if the sound’s loudness changed rapidly but the fish’s size changed slowly, for example — players performed less well. And when the game was mute, players fared even worse than they did when their eyes and ears were both engaged.

The research suggests humans perform best when multiple senses are involved and sensory inputs agree with one another. “Any time you have multiple sources of information and they’re correlated, performance improves,” Sekuler says.

Want to win at your favorite video game? Keep the sound on.