Turning Points

Driving Mrs. Roosevelt

Alyssa Carvara

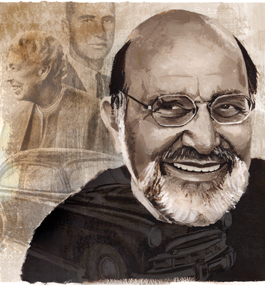

by Allen Secher ’56

For five days in 1955, I was in the driver’s seat. And former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt sat by my side.

This unlikely pairing was due to Brandeis, of course. One of my student jobs was working as a campus guide in the public relations department. During graduation week, my responsibilities expanded to serving as a chauffeur for visiting dignitaries. A member of the university’s Board of Trustees, Mrs. R would be coming to campus for the Commencement festivities and a board meeting.

As graduation approached, I begged, pleaded with and cajoled the PR director to let me be the one to drive her. With some hesitancy, he gave in.

Day one arrived. I went to the fancy Beacon Hill townhouse where Mrs. R was staying to pick her up. Beyond nervous, I pressed the call button. “We’ll be right down,” a voice said. The elevator opened, and out she strode with her hostess. She extended her hand and said, “How do you do? I’m Anna Eleanor Roosevelt.”

As if I didn’t know.

I escorted Mrs. R and her hostess to my beat-up 1949 Chevy. “Mrs. Roosevelt,” I said, “you are about to ride in the only car about which a song has been written.”

“How so?”

“‘Shake, Rattle and Roll,’” I said.

She chuckled.

Unsure of the protocol, I opened both the front door and the back door. Mrs. R slid into the front seat. Her friend sat in back.

On every trip we made — there would be at least 10 of them — Mrs. R sat next to me. She never treated me as the chauffeur. I was the driver, and I was always, even when others were present, included in the conversation. When we were alone, we talked as two acquaintances, comfortably sharing thoughts and opinions. I never felt demeaned or patronized. My youthful thoughts were accorded a welcoming ear.

Students were banned from driving on campus during graduation week. Once when I was trying to get Mrs. R conveniently close to a campus event, university photographer Ralph Norman stepped in front of my car, and started yelling and cursing at me for defying the ban. As surreptitiously as I could, I pointed at Mrs. R. Ralph turned all shades of red, apologized profusely and waved us through.

In addition to my duties with Mrs. R, I was also asked to drive another VIP and his spouse to campus. As soon as the two of them arranged themselves in my back seat, the wife began complaining loudly. “How could they have sent such an inappropriate, beat-up car?” she said.

The bellyaching lasted four or five blocks. When I couldn’t take it any longer, I pulled over to the side of the road and turned to face my passengers. “Look,” I said, “for the past three days, Eleanor Roosevelt has been riding beside me in this beat-up car. If it’s good enough for Eleanor Roosevelt, it should be good enough for you.”

When we got to campus, I requested a new driver for them.

Perhaps the best example of Mrs. R’s fellow feeling happened during an evening arts performance at the outdoor Ullman Amphitheatre. When we arrived, rain was threatening. I suggested that if it rained and she wished to leave, she should just stand up and I’d race for the car. The rain came. I ran to get the car. When she and a male companion got in, the conversation went like this:

“Allen, you’re soaked. We’re not going anywhere until you go home and change clothes.”

“But Mrs. Roosevelt, I live on Moody Street in a walk-up above a brothel and a gin mill in the scuzziest part of town.”

“Doesn’t matter. We’re going.”

So while she and her guest sat in my parked car in front of the bar, I made a record leap up three flights, changed clothes and rushed back down to the driver’s seat.

A week or so later, when I returned home to Pennsylvania, a personal letter from Mrs. R awaited me, thanking me for my service. I cherish the letter. In fact, I still bask in the glow of my time with her.

Mrs. R was an example of grace personified. In a self-involved world, where the rich and famous live in an alternative universe, I learned a powerful lesson from her: Position and wealth don’t matter.

What matters is a sense of shared humanity, which allows everyone to sit in the front seat of life.

Allen Secher is a rabbi and a civil- and human-rights activist living in Whitefish, Montana.