Imprint

A page from a story about Leo Frank in the August 1915 issue of Watson’s Magazine, a copy of which is in the Leo Frank Trial Collection. The magazine played a prominent role in inflaming public opinion against Frank.

Digitizing Materials From the Leo Frank Case, a Still-Relevant ‘Story of Hysteria’

On Aug. 17, 1915, armed vigilantes entered a Georgia prison farm, abducted a Jewish man named Leo Frank, drove him 150 miles to the town of Marietta and — near the home of the teenage girl Frank had been convicted of murdering — hanged him from an oak tree. The next morning, 3,000 people gathered to view the dead man’s body, still dangling from a noose.

A century later, the notorious case of Leo Frank still reverberates. “It hits all the buttons,” says Thomas Doherty, professor of American studies at Brandeis. “Class, region, race, religion and sex — it’s got it all.”

The Leo Frank Trial Collection, which includes letters Frank sent his family from prison, is among the holdings in Brandeis’ Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections that have been selected for digitization. The Brandeis National Committee’s Honoring Our History campaign is seeking to raise $500,000 to make these unique collections, which focus on such themes as the Jewish experience, immigration, feminism and resistance to persecution, available electronically to scholars around the world.

Leo Frank was a Northerner who worked as a superintendent at an Atlanta pencil factory. In 1913, he was convicted of the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, whose body was found at the factory. The trial sparked a sensation marked by a strong current of antisemitism. When Georgia’s Gov. John Slaton, who had doubts about Frank’s conviction, commuted his death sentence, Frank was abducted from jail and lynched. Most present-day historians believe Frank was wrongly convicted. In 1986, the state of Georgia granted him a posthumous pardon.

“The trial and subsequent lynching of Leo Frank has been called a Dreyfus Affair in Georgia,” says Stephen Whitfield, PhD’72, the Max Richter Professor Emeritus of American Civilization, and the events “undermined the confidence of many Southern Jews that they were safe.” Just months later, many of those who made up the lynch mob took part in the Stone Mountain ceremony that established the modern Ku Klux Klan.

Notoriety aside, the case remains relevant, scholars believe. “It’s a story of hysteria,” Doherty says. “When the fever breaks, you look back on it and ask, ‘How could we have been so crazy and irrational?’ That might be one of the lessons today. We do seem to be in this moment of cultural hysteria.”

Brandeis’ Leo Frank Trial Collection consists chiefly of correspondence written by Frank and his wife, Lucille. It also includes correspondence to and from Slaton and others, as well as miscellaneous articles, pamphlets and legal documents.

The collection was donated to the university in 1961 by Harold and Maxine Marcus, who received the papers from Lucille Frank, who was Harold’s aunt. The Marcuses were generous donors to Brandeis during the university’s early years, and Maxine was a founding member of the Atlanta Chapter of what was then called the Brandeis University National Women’s Committee.

The Frank papers, particularly his letters, are a significant scholarly resource, says Doherty: “It’s wonderful Brandeis has them. The final letters are so eloquent when he’s writing to his wife. You really get a sense of his courage.”

Merle Eisman Carrus, P’12

Meet the New BNC President

On July 1, Merle Eisman Carrus, P’12, succeeded Madalyn Friedberg in the role of Brandeis National Committee president.

An inveterate bibliophile (who blogs at Bite of the Bookworm), Carrus has been a BNC vice president, a leader of the Greater Boston Chapter and the New England Region president.

Here is an edited portion of an interview she did in June with the Brandeis Alumni Association.

What does Brandeis mean to the Carrus family?

We have a strong family connection with Brandeis. My mother-in-law, Jean Carrus, G’12, sat on the BNC’s national board and was a Western Region president. My daughter, Danielle ’12, MAT’14, has great memories of her campus experience. We are all life members of the BNC.

Does the Honoring Our History campaign take on new relevance during the pandemic, when activities like using the library are often done remotely?

For me, one of the BNC’s most attractive qualities is its connection to the library. I am passionate about reading and books. And having worked in a role that required me to do quite a bit of research before the advent of the personal computer, I can really appreciate the ease of this amazing world of digitization. During a pandemic, it is incredibly valuable to have digitized archives that researchers can access.

The Honoring Our History campaign is so important to the continued history of the BNC. We have filled the library’s physical shelves with books. Now we are helping to preserve the library’s archives for the future.

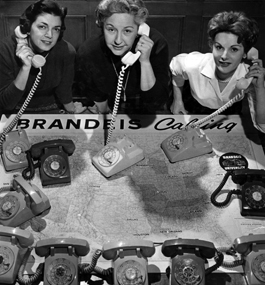

Brandeis Calling

In 1959, members of the Brandeis University National Women’s Committee hosted a nationwide telethon to raise money for library books for the decade-old university. More than 60 years later, the Brandeis National Committee is still sharing its message far and wide. After the COVID-19 pandemic halted in-person chapter events, the BNC began hosting fundraising events via Zoom to unify members across the country around its founding mission: supporting Brandeis and its libraries. Learn more about upcoming events and the BNC’s Honoring Our History campaign by visiting the newly redesigned website at www.brandeis.edu/bnc.