The True Story of ‘the Moses of Her People’

On the bicentennial of Harriet Tubman’s birth, separating fact from fiction.

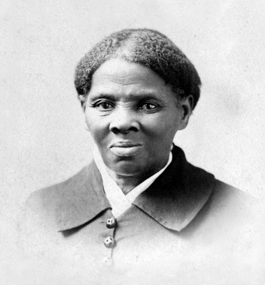

Harriet Tubman

by Kate Clifford Larson

This year marks the 200th birthday of one of America’s most daring freedom fighters.

Harriet Tubman — who was named Araminta “Minty” Ross when she was born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the late winter of 1822 — learned at age 27 that her widowed enslaver, Eliza Brodess, intended to sell her to pay mounting debts. Desperate to avoid an unknown future in the cotton fields of the Deep South, Tubman determined she would have her liberty or death.

With the aid of sympathetic helpers along a network known as the Underground Railroad, she escaped to the free city of Philadelphia. Once there, she realized she could never be completely free while her loved ones remained enslaved. Over the next 11 years, she repeatedly returned to Maryland to liberate family members and friends, earning national prominence and the nickname “the Moses of her people.”

I have been researching and writing about Tubman for more than 25 years, after she captured my imagination when I was a graduate student in the 1990s. By then, she had been famous for almost 150 years. Library shelves were filled with scores of mostly fictionalized works about her life written for young readers. But I was surprised to discover only three Tubman biographies aimed at adults: two brief 19th-century accounts, published while she was still alive, and a book published in 1943.

One stumbling block for would-be biographers was that Tubman, denied a formal education, had never learned to read or write, so she left behind no collection of personal papers for scholars like me to mine.

However, I discovered that New England archives were treasure troves of Tubman information. Many prominent New England families had been deeply committed to the abolition cause. Some of the most important of them befriended Tubman after she liberated herself. Inspired by her courage, intellect and moral certainty, they documented their conversations with her, wrote correspondence for her, and recorded their own memories and impressions of her.

In these New Englanders’ papers, I found accounts of Tubman’s activities as an Underground Railroad conductor, Civil War spy, soldier, nurse, woman suffragist, civil rights activist and humanitarian. They expressed profound admiration and respect for the power of the petite, 5-foot-tall Black woman who refused to give up. They loved her, sincerely and genuinely.

Researching Tubman’s life as an enslaved person proved more difficult — but not impossible. In Maryland, I found court records, tax documents, bills of sale, and other private and public records that documented her family and her community’s history. I learned about the people who helped raise, protect and educate her, and who helped her secure freedom for herself and others. I explored the physical landscape of the Eastern Shore. I learned how she survived and escaped the hostile world of enslavement.

I found a number of truths that had long been obscured by the fakelore, exaggeration and hagiography surrounding Tubman. Some examples:

• Although Tubman was illiterate — she could not read or write text — she had many skills I would describe as “literacies.” Growing up in a maritime community alongside the Chesapeake Bay, she knew how to read the night sky, rivers, streams, marshes, woods and fields. She knew how to read the character of the people she met. Bright and confident, she used her knowledge to navigate undetected through dangerous physical and human landscapes, and bring people to freedom.

• As a young teen, she suffered a traumatic brain injury that nearly killed her. For the rest of her life, she endured epileptic seizures. Early biographers called them “sleeping spells.” In truth, her epilepsy was a profound disability that challenged her health and safety every day.

• Sarah Bradford, an early Tubman biographer, wrote that Tubman had rescued 300 people over the course of 19 trips during the 1850s. This was a complete fabrication. Tubman actually freed about 70 enslaved family and friends in 13 rescue missions — still a remarkable achievement.

Susan Wilson

Kate Clifford Larson

page 2 of 2

• Many myths have grown up about secret signals — quilt codes, lawn jockeys, the song “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” to name a few — that were used along the Underground Railroad. Most of these stories are fakelore, manufactured in the mid- to late 20th century. However, Tubman did mimic the hoot of an owl to communicate to her followers. She would also sing two Christian spirituals — “Go Down, Moses” and “Bound for the Promised Land” — to signal whether it was safe to come out of hiding.

• Few people know that, during the Civil War, Tubman became the first American woman to lead an armed military raid, guiding Col. James Montgomery and his 2nd South Carolina Black regiment around mines planted in South Carolina’s Combahee River as they attempted to rout out Confederate forces. After the regiment’s raid liberated more than 750 enslaved people, newspaper headlines credited the “Black she-Moses” for the successful military expedition. At her funeral in 1913, Tubman received semi-military honors. In 2021, the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame inducted her into its ranks as a full member, for her service to her country.

• When Tubman escaped slavery in 1849, her enslaver posted in local newspapers a notice of a $100 reward for her capture and return, at the time a typical amount given for the apprehension of a freedom seeker. Twenty years later, anti-slavery activist Sallie Holley asserted the reward amount for Tubman had been $40,000, a fabricated figure still quoted today. Consider that $40,000 in 1849 would be equivalent to several million dollars today. For that amount, Tubman almost certainly would have been captured.

After risking her life again and again to claim freedom for herself and others, Tubman in spring 1859 purchased a small farm on the outskirts of Auburn, New York, from William Henry Seward, President Abraham Lincoln’s future secretary of state, and his wife, Frances. Tubman spent her last 50 years living there in freedom.

During those years, she fought for civil rights and woman suffrage, campaigned for housing and medical care for aged and disabled African Americans and poor whites, and advocated for measures that addressed food insecurity. When she died in 1913 at age 91, The New York Times included her in its list of the world’s most important people to die that year.

Tubman’s history deserves truthful depiction, rooted in her own words and well-documented deeds. We can celebrate her more fully and respectfully without the myths and inaccuracies that have obscured her story for so long.

In the U.S., her name has been given to two new national parks, a Maryland state park, and a National Scenic Byway and All-American Road. Her story has inspired public memorials and books, a documentary, and a feature-length film. Perhaps most fittingly, the U.S. Treasury is redesigning the $20 bill to put her portrait on the front, for release in 2030.

Why does Harriet Tubman matter so much? Because she represents ideals that Americans hold dear, ideals that many people all over the world yearn for — freedom, equality, justice and self-determination.

Kate Clifford Larson is a visiting scholar at Brandeis’ Women’s Studies Research Center. Her books include “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” (Oxford University Press, 2021) and “Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero” (One World/Ballantine, 2004).