Brandeis on the Air

In the internet age, college radio stations still offer students an electrifying mode of self-expression.

By David Levin

Photography by Dan Holmes. Archival images courtesy Robert D. Farber Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis

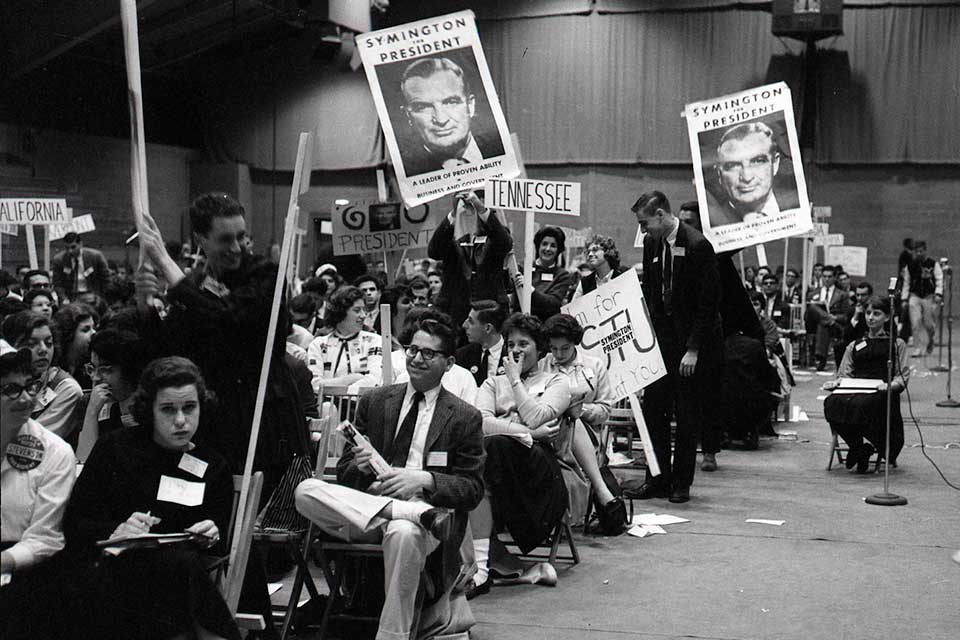

Looking back, the pre-internet media landscape seems almost quaint. Late into the information age, mobile phones were unwieldy plastic bricks, video rental stores were a booming business, and broadcast TV and radio ruled supreme. The halls of mainstream mass media remained closed to all but a handful of professionals.

On the margins, though, a small but effective backdoor offered admittance to outsiders.

For decades, college radio stations like Brandeis’ WBRS 100.1 FM have thrived on campuses nationwide. From its first transmission in 1968, WBRS offered something students found nowhere else: free and independent access to the airwaves. Even if its signal barely reached past Waltham and its surroundings, the station has given generations of students and community members a way to have their voices heard. For many DJs who passed through its studio, this power was intoxicating.

Today, broadcast media aren’t nearly as rareified. With a few taps on a smartphone, students can access countless sources of news, music, and other new media anytime. Tuning in to a single radio station at a predetermined time to do the same feels hopelessly out of date.

Not that this is stopping anyone at WBRS. Although many of the station’s current DJs say radio is “dying,” “antiquated,” or “won’t be around for long,” they also, paradoxically, express a lasting devotion to it as a medium.

Their interest in the magic and serendipity of live broadcast is as strong as ever.

‘The freedom was a rush’

Working in the WBRS studio allows students to physically immerse themselves in a campus tradition that generations of students have built and maintained.

“The freedom we had on-air was a rush,” remembers former DJ and WBRS news anchor Lisa Stein Fybush ’91. “Everybody on staff developed this really deep passion for the station. Some people were so devoted to it, they would stay at Brandeis over vacations — even through the summer — just to make sure it stayed on the air. We were that protective of it.”

For Stein Fybush, being involved with WBRS was life-changing. In addition to providing her first on-air experience, the station is where she met her future husband, Scott Fybush ’92, who was then its news director.

To this day, the pair are still involved in radio, in Rochester, New York. Fybush is a part-time host on WXXI 105.9 FM, the city’s NPR station and, with his wife, publishes a weekly newsletter devoted to radio news and history in the Northeast and Canada. Stein Fybush hosts “The Tragical History Tour,” a Beatles-themed show on Rochester’s community-run station, WRFZ 106.3 FM, which she syndicates to other independent stations nationwide.

During my own stint on college radio in the late 1990s, taking command of the airwaves became almost a religious experience. Being on the air felt visceral, transcendent, and deeply personal.

Like WBRS, my college station was a valuable voice for our community. Independent radio was an essential clearinghouse for new ideas, music, and art; maintaining that service carried considerable weight.

Stopping our broadcast, those of us who worked there reasoned, would rob the region of a fundamental public service, almost akin to torching the public library. So for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, someone from our small band sat behind an old mixing board in a dingy studio, dutifully keeping the eternal flame of broadcast burning.

Moving past boundaries

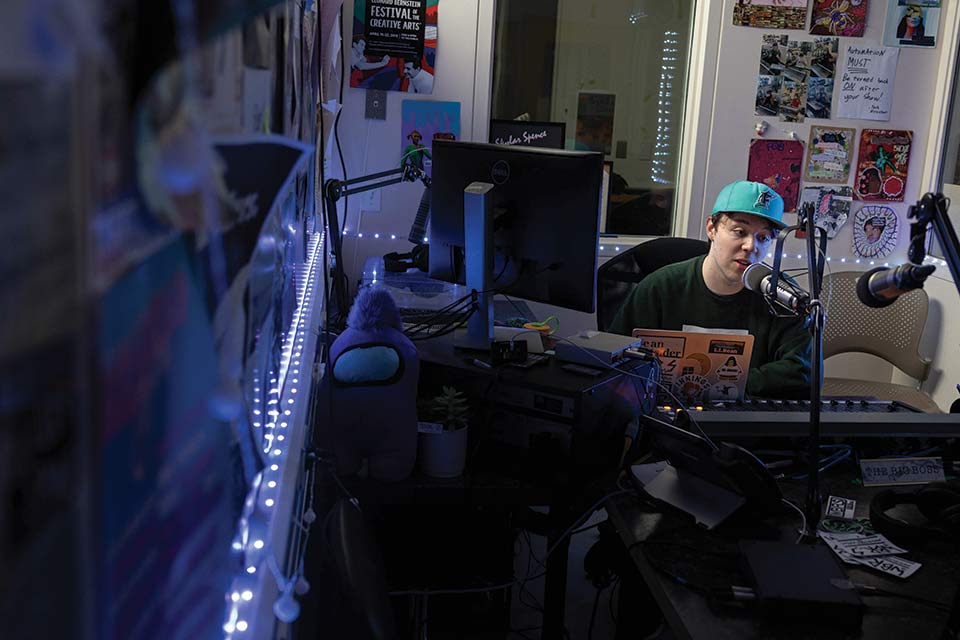

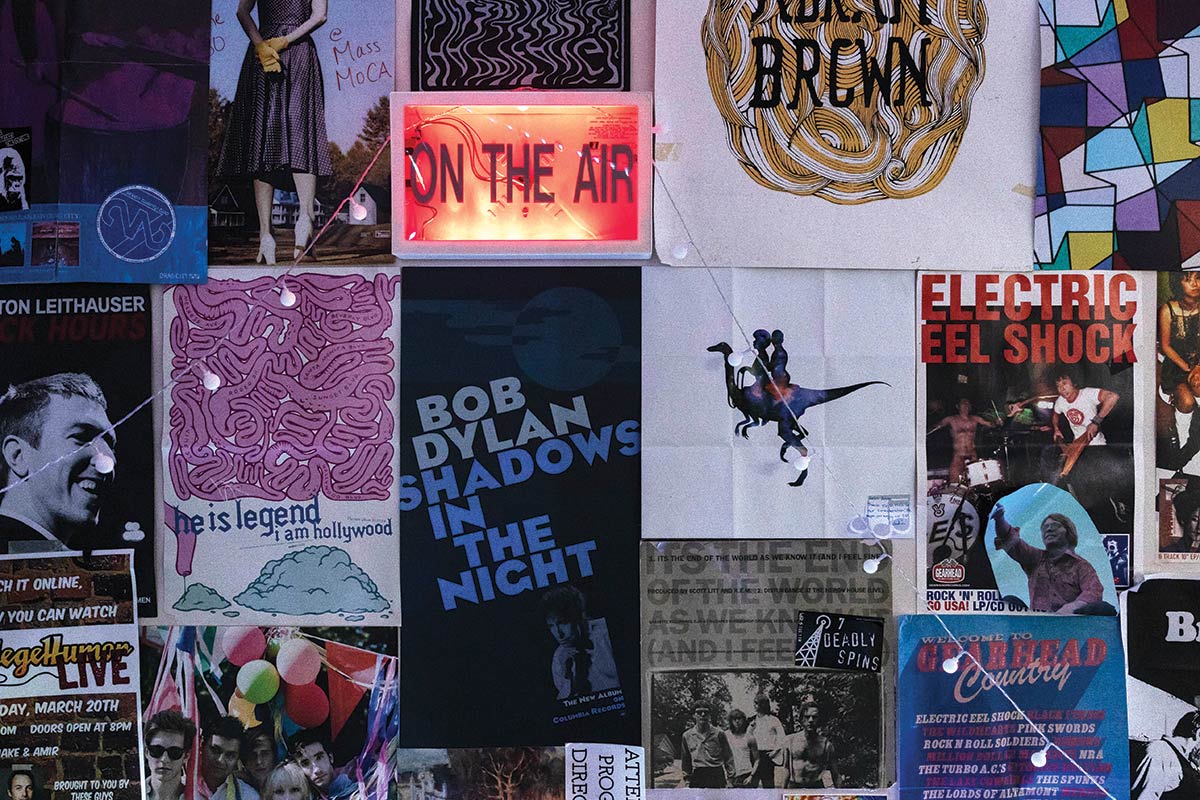

At Brandeis, WBRS’ lived-in vibe creates a safe space for experimentation. In a corner suite on the third floor of the Shapiro Campus Center, the station’s eclectic nature is on full display. Walls are almost entirely covered in posters from obscure bands and record labels. Racks of CDs, vintage vinyl, and promotional tchotchkes line the corridors. Ancient couches are jammed into a makeshift lounge. Inside jokes from past DJs are scrawled in marker on the windows that separate the studio’s five rooms.

It’s exactly what you’d expect a college station to look like.

Like the students who pass through the station’s doors, WBRS shows are distinctive, bold, and sometimes fantastically eccentric. Well-worn favorites like classic rock and sports talk are part of the rotation. But DJs also play vintage Japanese funk, live electronic music, Bollywood soundtracks, Celtic folk, and spoken-word poetry. From one hour to the next, there’s no telling what you’ll hear.

This suits programming director Willow Bosworth ’25 just fine. “I hate genre. The whole concept of it is just really limiting,” Bosworth says. “Genre titles are just a lot of meaningless words that get thrown around — at the end of the day, the focus should be about what the artist puts into their music.”

Bosworth (who uses they/them pronouns) puts this philosophy into practice during their genre-agnostic show, “Willowcore,” which centers around music that resonates with them emotionally, regardless of its origins. An hourlong show might meander from folk-adjacent singer-songwriters to experimental noise.

Having this kind of carte blanche at the mixing board is a major draw for the station’s business manager, Sophie Kaye ’26. “When you walk into the station, it has a different energy than other places on campus,” she says. “There are no barriers to being creative here. If you wanted to have a show that was just an hour of cat sounds, there wouldn’t be any objections.”

As Bosworth and Kaye note, there’s a certain liberation in removing boundaries. It clears the path for unencumbered expression of a DJ’s own artistic vision.

Emilia Brandimarte ’25 created her show, “I Am the Arm,” as an homage to filmmaker David Lynch. In high school, Brandimarte says, she crafted mixtapes of music that appeared on Lynch’s soundtracks, interspersing the songs with obscure dialogue from his films. As a first-year, she realized those playlists would make the perfect basis for a radio show, which she now hosts weekly from midnight to 1 a.m.

“When you walk into the station, it has a different energy than other places on campus. There are no barriers to being creative here.”

Sophie Kaye ’26

The scheduling is no accident. “Being a late-night thing helps keep it kind of strange and eerie, especially if people are just stumbling onto it with no context,” she says. “You’re never really sure who’s out there. I love the idea that people could find my show unexpectedly late at night while driving down I-90.”

Broadcast’s ephemeral nature is part of its allure. In an age where much of our lives is documented on social media, hosting a live show is almost a meditative act; it forces DJs to live entirely in the moment.

“I always approach my show with the mentality of ‘no one’s listening,’” says Joshua Hertz ’25, the station’s co-general manager. “I mean, I’m sure there are some people listening, but I have no way of knowing who is or isn’t unless I get a text message from a friend or my parents. When I’m on the air, I just try to have fun and live in the present.”

Evocative overtones

The idea that WBRS is, at its core, a platform for self-expression seems to be a near-universal sentiment among its staff. It doesn’t matter which niche interest each of them brings to the table. They all feel an irrepressible urge to share these passions with others.

This common thread holds the station’s community together, both on and off the air. The current batch of DJs, Hertz says, frequently appear on one another’s shows and hang out at the station even when they’re not working.

“A few years ago,” says WBRS co-general manager Ariella Weiss ’24, “we had a stationwide zine night, where people got together and made their own collage out of old magazines. We compiled all the collages into a book, printed it, and distributed it around campus. That really represented the spirit of the station. People just want an outlet to create, and the station provides that in so many different ways.”

In a sense, making paper collages for a zine — a retro act in a digital world — is a fitting metaphor for the station. Each time they go on the air, these students have a chance to craft a one-of-a-kind program that is uniquely theirs, delivering it to the world at 100.1 MHz.

And, like a zine, the station’s shows are produced with a nostalgic overtone. Their creators have seen mass media change wildly over the short span of their lives. At a time when smartphones incessantly demand our attention, WBRS DJs express a love for “antiquated technology” and the way things “used to be done,” as if doing radio were an act of historic preservation.

There’s a kernel of truth there. Doing radio is a way to be part of a continuum that, with any luck, will exist long after the DJs have graduated. In the present moment, it offers a powerful way to spread joy through raw creativity.

“People like us love WBRS because it makes people happy,” says Weiss. “There’s no better justification for doing it than that. If you give a freshman the ability to put their music on-air, that’s really impactful — it encourages them to continue pursuing an interest they are drawn to.

“I’ve loved being able to help make that a reality.”