Rooms of Their Own

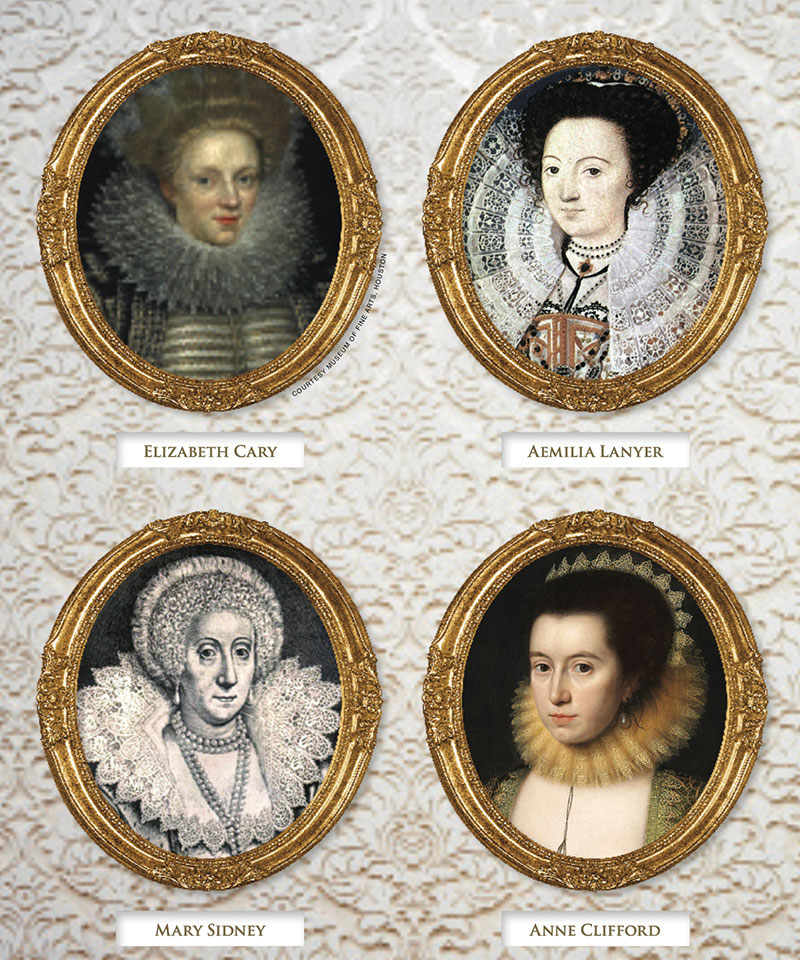

English professor Ramie Targoff casts light on four overlooked female writers of the Renaissance.

By Sarah C. Baldwin

In the late 1590s, Elizabeth Cary, a member of the English bourgeoisie, wanted to give her well-traveled great-uncle a present. So she set about translating the nearly 100 French texts that supplemented the maps in the world’s first modern atlas, published in 1570, writing her translations out in calligraphy. She was 13 years old.

Elizabeth, who could read at 4, began teaching herself French, Italian, Spanish, and Latin as a child. When she gave her great-uncle her French-to-English translations, she had already translated Seneca’s “Epistles” from the original Latin.

Before she turned 30, she wrote “The Tragedy of Mariam,” a dramatic retelling of Herod’s murder of his innocent wife. It was the first original play by a woman published in England.

When Ramie Targoff, the Jehuda Reinharz Professor of the Humanities, was a student delving deeply into Renaissance literature, she was never introduced to Elizabeth Cary’s “Mariam” — or, for that matter, to any text written by a woman.

Our historical conception of the Renaissance — including the women of the Renaissance — has been shaped solely by “the male understanding of the world,” Targoff says.

In her latest book, “Shakespeare’s Sisters: How Women Wrote the Renaissance” (Knopf, 2024), Targoff, a professor of English and the co-chair of Italian studies at Brandeis, sets out to enlarge this conception. Against the backdrop of Elizabethan England — think smallpox and bubonic plague, banishments and beheadings, conspiracies and kidnappings, and the staggering extravagance of royal weddings and funerals — she weaves together the lives and literary accomplishments of Elizabeth Cary and three other talented Renaissance women, for whom writing was not just a life force but a lifeline.

In her latest book, “Shakespeare’s Sisters: How Women Wrote the Renaissance” (Knopf, 2024), Targoff, a professor of English and the co-chair of Italian studies at Brandeis, sets out to enlarge this conception. Against the backdrop of Elizabethan England — think smallpox and bubonic plague, banishments and beheadings, conspiracies and kidnappings, and the staggering extravagance of royal weddings and funerals — she weaves together the lives and literary accomplishments of Elizabeth Cary and three other talented Renaissance women, for whom writing was not just a life force but a lifeline.

In doing so, Targoff offers a convincing refutation of the claim Virginia Woolf makes in her essay “A Room of One’s Own”: “It would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare.”

Not that Woolf was wrong to be dubious. The cards were stacked against Renaissance women. The rate of literacy among women in London hovered around 10%. Girls were not sent to school. If they were educated, it was usually at home, where they were more likely to learn music and dance than Greek and Latin.

Within the higher echelons of society, girls were often, in Targoff’s words, “picked to breed” — married off by their parents to produce a male heir and cement strategic alliances that would enrich their families. Wives became the property of their husbands, who also gained possession of any property their wife owned. Women couldn’t sign contracts or make wills. They couldn’t vote, much less hold political office, or act onstage. In this era of austere Protestantism, an Englishwoman’s most prized virtue was her silence.

And yet Targoff introduces us to four Renaissance women who were educated, erudite polyglots (not unlike their queen, Elizabeth I) for whom self-expression was a vital creative and emotional outlet.

Despite lives restricted by the obligations of womanhood, wifehood, and motherhood, each found ways to make important contributions to English poetry, drama, memoir, and history.

Challenges to the patriarchy

Ramie Targoff (Photo Credit: Judith Clark)

Ramie Targoff (Photo Credit: Judith Clark)

Take Mary Sidney, another Renaissance woman Targoff spotlights. Her marriage, at 15, endowed her with a new title (Countess of Pembroke), a sumptuous home, 200 servants, and an unappealing 38-year-old husband.

Mary’s first foray into the literary world was to edit and publish the works of her beloved brother Philip, a writer who was killed in battle fighting the Spanish. She started writing her own poetry and translations, doing what few (if any) aristocratic women before her had done: She published her work under her own name.

Then “Mary secured a hallowed place for herself in the annals of literary history,” Targoff writes, by becoming the first person to transform the entire Book of Psalms from prose into a work of sophisticated English poetry. One of her contemporaries, the metaphysical poet John Donne, praised the poems, claiming they “teach us how to sing.”

Targoff calls Mary’s work “dazzling.” More radical still, she says, Mary “brought to the supremely patriarchal texts a distinctly female voice.”

A decade later, Mary proved a source of inspiration for another aspiring devotional poet, Aemilia Lanyer. The daughter of an Italian recorder player in Queen Elizabeth’s court, Aemilia was a middle-class girl whose poetic awakening was fueled by the time she spent, first as a ward and later as a tutor, in two different households run by educated women. Aemilia’s ambitions were temporarily thwarted when she became pregnant by her secret lover, the chief of the royal household, who arranged her marriage to a court musician.

But at age 42, in 1611, the year the King James Bible was printed, Aemilia became the first woman of her century to publish a book of her own poetry. Her long poem “Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum” (“Hail, God, King of the Jews”) — more than 1,800 lines of iambic pentameter — was more than a literary feat. It was a feminist retelling of Christ’s Passion as well as an appeal for women’s rights. It was a challenge to the patriarchy.

Targoff’s fourth subject, Anne Clifford (another Countess of Pembroke) is the one she finds most fascinating, though, she admits, might be the most challenging of the four, too. Unlike her “sisters,” Anne was no poet — she was a diarist, memoirist, and historian.

A fierce, driven, and indefatigable woman, Anne, after being disinherited at 15 from her father’s vast property, devoted the next 40 years to fighting to regain her rights. When she finally prevailed, she spent her remaining years creating an almshouse, and crisscrossing the north of England to inspect and maintain her many castles.

Putting pen to parchment, she also wrote her autobiography, jauntily titled “The Life of Me.” In addition, she produced a complete genealogy of her family, which reached back to the Norman Conquest; handwritten, illustrated, and 1,000 elephant folio-size pages long, “The Great Books of Record” is today one of the most valued treasures in the Cumbria Archive Centre, in Kendal, England. Not surprisingly, the author figures in it prominently.

“Anne decided that her life and story mattered,” Targoff says.

An Elizabethan women’s network

The product of years of intense research, “Shakespeare’s Sisters” is a work of serious scholarship. Yet, like Targoff’s previous book, “Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna,” it was written with the public, not the academy, in mind. Targoff wants her research to reach as many readers as possible.

Toward this end, “Shakespeare’s Sisters” offers a trove of vivid, intimate details — from the astrologers the women consulted to the ribbons they used to seal their letters — that bring its subjects to life. Targoff spent hours handling original documents in the United Kingdom’s National Archives; she also visited every manor, castle, church, and tomb mentioned in the book, and even slept in what is said to be Anne Clifford’s bed.

Targoff’s book offers intimate details — from the astrologers the women consulted to the ribbons they used to seal their letters — that bring its subjects to life.

“We read statistics about widowhood, miscarriages, and infant mortality, but we don’t experience them from the position of the people who actually had to go through it,” Targoff says. “Only women could’ve written these things. They’re writing about what it means to be a woman.”

Works by Renaissance women remained mostly out of print (or incorrectly attributed) for nearly 400 years, Targoff says, because “certain figures get pushed forward and reproduced,” depending on “who we think counts.” Feminist scholars in the 1990s helped bring female Renaissance writers back into the public sphere, all in the space of a decade.

“It wasn’t a question of lost and found,” says Targoff. “It was a question of neglected and found.”

Rather than covering her subjects in four discrete sections, Targoff moves in and out of their stories, grounding each chapter in a particular day in one of the women’s lives, creating what she calls a “chronological domino effect” that moves the narrative forward. The fact that the women make appearances in one another’s chapters shows they moved in the same orbit and influenced one another’s lives.

“I thought of this as a kind of Bloomsbury story for women’s networks in this period,” Targoff says. “I wanted to get at the sense that women were connected to one another, indirectly making one another’s careers possible. Look at what it meant for Aemilia Lanyer to have Mary Sidney before her.”

When Aemilia includes Mary among her dedicatees for “Salve Deus,” implying she is Mary’s literary heir, Aemilia “aims to create the idea of a female legacy — a mantle that could be passed from one woman to the next,” Targoff writes. “In the absence of a female canon, Aemilia sought to invent one.”

Sarah C. Baldwin is a freelance writer living in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.