Turing’s theory of morphogenesis validated

Scientists from Brandeis University and the University of Pittsburgh show how identical cells differentiate

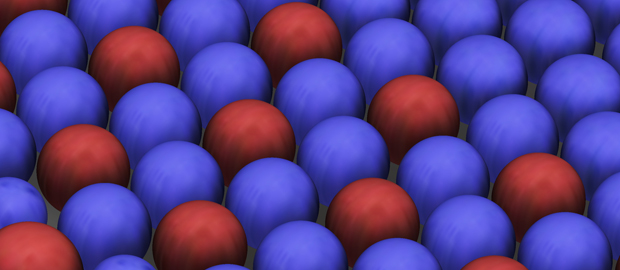

Courtesy of the Fraden Lab

Courtesy of the Fraden LabThe evolution of physical morphogenesis: cell-like structures change from all blue, to red and blue, to structures of different sizes.

Alan Turing’s accomplishments in computer science are well known, but lesser known is his impact on biology and chemistry. In his only published paper on biology, Turing proposed a theory of morphogenesis, the process by which identical cells differentiate, for example, into an organism with arms and legs, a head and tail.

Now, 60 years after Turing’s death, researchers from Brandeis University and the University of Pittsburgh have provided the first experimental evidence that validates Turing’s theory in cell-like structures.

The team published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 10.

|

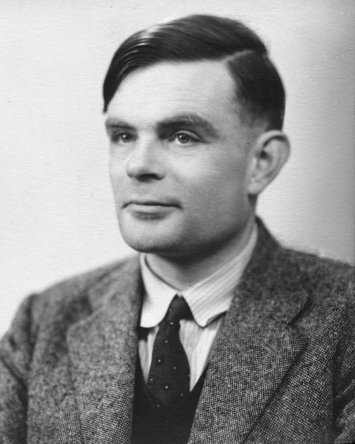

| Alan Turing |

Turing was the first to offer an explanation of morphogenesis through chemistry. He theorized that identical biological cells differentiate and change shape through a process called intercellular reaction-diffusion. In this model, a system of chemicals react with each other and diffuse across a space — say between cells in an embryo. These chemical reactions need an inhibitory agent, to suppress the reaction, and an excitatory agent, to activate the reaction. This chemical reaction, diffused across an embryo, will create patterns of chemically different cells.

Imagine a field, with grass as dry as bone, teeming with grasshoppers. A small fire starts in one patch of the field and the grasshoppers hop away to avoid it. As the bugs hop, they perspire, wetting the grass along the way. The fire jumps to another part of the field, the grasshoppers hop away, creating another island of wet grass.Now, picture an aerial view of this field — what was once a uniform plain is now spotted with patterns of burnt and unburned grass. This is Turing’s model of reaction-diffusion. The fire is the activator and the grasshoppers are the inhibitor. The reaction diffuses across a series of cells, activating some, inhibiting others and what was once identical is now different.

Turing predicted six different patterns could arise from this model.

Seth Fraden, professor of physics, and Irv Epstein, the Henry F. Fischbach Professor of Chemistry, created rings of synthetic, cell-like structures with activating and inhibiting chemical reactions to test Turing’s model. They observed all six patterns plus a seventh unpredicted by Turing.

Just as Turing theorized, the once identical structures — now chemically different — also began to change in size due to osmosis.

This research could impact not only the study of biological development, and how similar patterns emerge in nature, but materials science as well. Turing’s model could help grow soft robots with certain patterns and shapes.

More than anything, this research further validates Turing as a pioneer across many different fields, Fraden says. After cracking the German Enigma code, expediting the Allies’ victory in World War II, Turing was shamed and ostracized by the British government. He was convicted of homosexuality — a crime in 1950s England — and sentenced to chemical castration. He published “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis” shortly after his trial and killed himself less than two years later, in June 1954. He was just 41 years old.

Nathan Tompkins, Ning Li, Camille Girabawe from Brandeis University also contributed to this paper, along with G. Bard Ermentrout from the University of Pittsburgh.

The research was funded in part by from the National Science Foundation Material Research Science and Engineering Center grant DMR-0820492 and grant CHE-1012428.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology