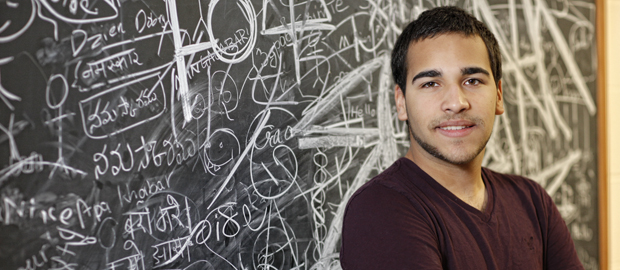

Jose Vargas ’15 brings astrophysics down to Earth

Photo/Mike Lovett

Photo/Mike LovettJose Vargas ’15

Jose Vargas ’15 couldn’t see much of the night sky from his apartment in Brooklyn, N.Y., but that didn’t dampen his curiosity. When most kids his age turned on the TV after school, Vargas opened up encyclopedias in his public library, exploring the universe from its worn pages.

After four years at Brandeis, Vargas has seen further into the night sky than most people on Earth but he hasn’t forgotten what it was like to be an 8-year-old in Brooklyn, straining to see a few stars. When he graduates in May, Vargas will take his physics degree back to New York City and teach high school physics through Teach for America.

“I want to help kids discover what they are passionate about,” Vargas says. “I’ve had so many teachers support and inspire me, in high school and at Brandeis. I want to do the same.”

Astrophysics professor John Wardle is one of those mentors.

Vargas came to Brandeis as a member of the Brandeis Science Posse, a scholarship and mentoring program that identifies and supports students in STEM fields. The highly competitive program chooses 10 students from hundreds of applicants in New York City and, in the year before college, helps them build a support system — their posse — and prepare them for college life.

Posse members spend the summer before freshman year in an intensive science boot camp that places them in campus labs and gives them their first taste of college research.

During his boot camp, Vargas spent time in biology and chemistry labs but Wardle’s astrophysics lab made him starry eyed.

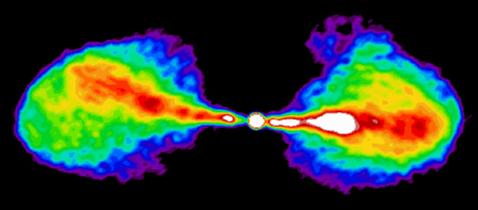

The Wardle lab studies quasars, the brightest and most remote objects in the universe, 10 to 12 billion light-years away, using the world’s most powerful radio telescopes.

Quasars form when supermassive black holes — billions of times the mass of the sun — feed on nearby material. The matter forms an accretion disk around the black hole, heating up to millions of degrees and blasting out radiation and powerful jets of particles, which travel at nearly light speed. Astrophysicists believe that quasars may be an important step in the birth of galaxies.

|

|

The quasar's jets are clearly seen in this image, compiled by the Very Large Array telescope. |

Vargas joined the lab after his sophomore year and began working with Wardle to collect data from the telescopes in order to study how quasars evolve. Because the quasars are so far away, Vargas was not only looking across space, he was looking back in time.

“It’s just so cool,” he says, emphasizing each word. “I’ve loved every second in the lab because the work is so interesting and professor Wardle is so passionate about what he does.”

Under Wardle’s guidance, Vargas is working on his first publishable academic paper on the project.

Vargas says he will miss research when he trades the college lab for the high school classroom in September, but he says he will never stop being curious.

“I’m still going to keep track of all the new developments in physics, and I hope to get my students as excited about it as I am,” he says.

ReAction, the Brandeis University Science and Research Blog, asked Vargas to describe what it’s like to see into the past. Visit ReAction to see his answer.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology, Student Life