Remembering Shimon Peres’ legacy for Israel and the world

Brandeis professor Yehudah Mirsky discusses the legacy of a controversial, yet respected, Israeli political figure

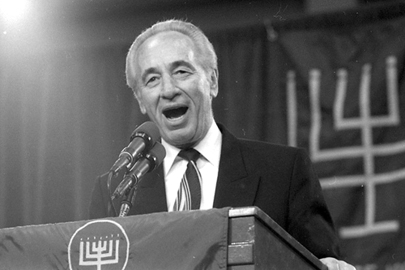

Photo/Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department

Photo/Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections DepartmentFormer Israel Prime Minister Shimon Peres, H’97, died on September 28 in Tel Aviv at age 93. The last member of Israel’s founding generation to serve in public office, Peres’ was a complex figure who achieved the status of elder statesman at a time when most of his contemporaries and opponents had long since left the political stage.

Peres was a key figure in Israel’s nuclear armament, and was also a leader of Israel’s efforts towards peace with its Arab neighbors. Along with Yitzak Rabin and Yasser Arafat, Peres was a chief architect of the 1993 Oslo Accords in which Israel and the PLO agreed to mutual recognition. Peres visited the Brandeis campus in 1994, the same year he, Rabin and Arafat received the Nobel Peace Price. In 1997, Brandeis awarded him an Honorary Degree. Peres served as Israel’s Prime Minister twice and as its President and head of its Defense Ministry.

BrandeisNOW spoke with Yehudah Mirsky, Associate Professor of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies, member of the faculty of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies, and a former official of the US State Department, about Peres’ significance to Israel and the world.

BrandeisNOW: What is Peres’ legacy to Israel?

Yehudah Mirsky: Peres’ legacy is large and certainly complicated, and it will be remembered and contested over time. On the one hand, he is a figure that has been lodged at the center of Israeli policy for decades. He never served in the Israeli army but headed its Defense Ministry, one of a number of ways in which he was central to Israeli society while at the same time running along side of it.

He did sometimes – deservedly – have a reputation of being cynical and manipulative. He was a controversial figure in Israel for much of his career. He never had electoral success as Prime Minister – when he took the office it was largely because of coalition building agreements, and of course, the assassination of the previous Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin.

What’s extraordinary with Peres, though, was his final act of his very dramatic life, when he became President. Though it’s a ceremonial position, he held it with dignity and, in his last years, managed to achieve stature as a dignified national statesman. As a political figure, that reputation had eluded him for many years.

BNOW: How did Peres establish himself as a leader in the international community?

YM: He is universally adored in America and among American Jewry, even though he was a controversial figure inside Israel. This is yet another example of how the real-life Israel regularly differs from the Israel of American-Jewish imaginations.

I saw first hand his leadership in 2008 when I served on the organizing committee of a massive international conference Peres hosted in Jerusalem to honor the 60th anniversary of the state of Israel. He had a whole raft of people in Jerusalem celebrating the creation of the state, from Sergei Brin and Henry Kissinger and Elie Wiesel, to leading rabbis, scholars, businessmen and an amazing cross-section of Israeli society, Jewish and non-Jewish alike. Only Peres could have pulled that off. He was truly a man of the world whose cosmopolitanism and commitments to Zionism and Israel went hand in hand.

BNOW: Peres led Israel’s Defense Department and created their nuclear program while simultaneously advocating for peace between Israel and the rest of the Arab world. How could he reconcile two mentalities of seemingly opposite poles?

YM: For Peres, there was no contradiction between the two. Both were about securing Israel’s long-term existence and security. To that end, nuclear weapons were a necessary last resort.

Keep in mind that, at the time, in the 1950s and 1960s, Jordan occupied the West Bank and Gaza, Syria had the Golan Heights, Egypt had the Sinai, all the Arab states were pledged to Israel’s destruction and were by and large aligned with the Soviet Union, a nuclear power.

That was the context in which Peres understood that Israel needed [nuclear] capability. At the same time, he came to see that another dimension of Israel’s long-term existence and viability was its political and moral security, and that meant working to end a politically and morally unsustainable occupation of another people. The way he did this was via the Oslo Accords with Yasir Arafat in 1993, which he presented to Rabin as a fait accompli. This was, and remains controversial and history will judge whether it was indeed the best way to move forward. At this point, the evidence is deeply mixed to say the least.

BNOW: Peres was often described as forward-thinking. Would you agree with this?

YM: Peres focused on tomorrow, which was thrilling, but utopian. He had a way of not factoring into his thinking the tragic dimensions of things and the long shadow of history into his diplomatic and political work. Sometimes that tendency got in the way of what he was trying to accomplish.

He had a very forward-looking belief in technology, and his success with Israel’s nuclear program was just one example. He was always reading work on the cutting edge of things like nanotechnology, biotech and more. Another great achievement was his breaking the back of inflation in the 1980s and laying the groundwork for Israel’s embrace of free market, notwithstanding his roots in Socialism and early career as assistant to the founder of the State and lifelong Socialist, David Ben-Gurion. He played a key role in establishing Israel’s current economic success. That cannot be underestimated.

Most amazing was the closing act of his dramatic life, when he restored dignity to the office of the Presidency of Israel and became in this last, largely ceremonial position, the kind of conciliatory and unifying national figure he'd never been able to be in politics.

But he was always at his best, even in his 80s and 90s, while speaking to young people. He extended his vision, optimism and belief in the future in an inspiring way. He spoke in such a way that motivated young people to think about how they could bring out the best in themselves to make the world better than it is. This was extraordinary.

His greatest gift, certainly in these last years, was his optimism. We will debate his legacy for sure. For now, though, we who are here, and responsible in the present, can mark this moment in history when one of the last who was present at the creation has passed.

Categories: General, International Affairs