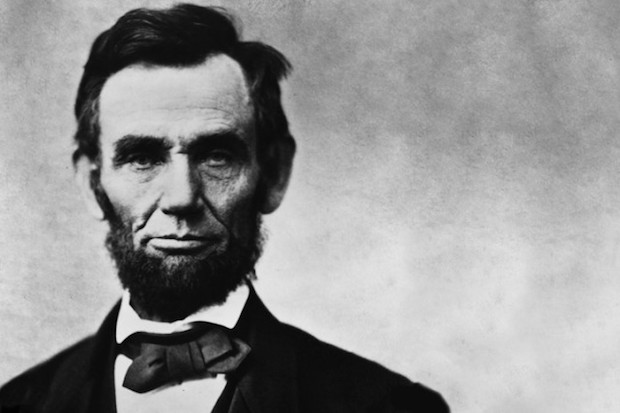

‘The party of Lincoln,’ 200 years later

photo/public domain

photo/public domainBrandeisNOW caught up with Brandeis Professor of English John Burt, author of “Lincoln's Tragic Pragmatism: Lincoln, Douglas, and Moral Conflict,” to talk about Lincoln and how he relates to the modern GOP.

Are there remnants of Lincoln’s values in the current Republican Party? Is it still ‘the party of Lincoln?’

Everybody has to claim Lincoln - nobody wants to restore slavery, no one wants to get rid of the 13th amendment - and everybody claims they understand Lincoln. At the same time, I would say the Republican Party of today is dominated by people who would have been Democrats until the 1940s.

Republicans had adopted a very racially progressive agenda during the 1950s - under Eisenhower they got 40 percent of the black vote. Southern Democrats, meanwhile, controlled the south and were rooted in a form of populism that emerged at the turn of the century with the rise of racist demagogues like Tom Watson and Ben Tillman. These Democrats represented white small farmers and small businessmen; they stood against black voters and strongly supported states’ rights and white supremacy. There were many racial progressives in the Democratic Party, but they had to act cautiously because their party depended upon support from these southern populists.

Republicans had adopted a very racially progressive agenda during the 1950s - under Eisenhower they got 40 percent of the black vote. Southern Democrats, meanwhile, controlled the south and were rooted in a form of populism that emerged at the turn of the century with the rise of racist demagogues like Tom Watson and Ben Tillman. These Democrats represented white small farmers and small businessmen; they stood against black voters and strongly supported states’ rights and white supremacy. There were many racial progressives in the Democratic Party, but they had to act cautiously because their party depended upon support from these southern populists.By the late 40s Democrats began to divide along racial lines. Truman and LBJ realized that the future of the party could not stand with white supremacists, first because of their own convictions, second because the political tide within the United States was turning against segregation, and third because segregation was an embarrassment internationally in the era of decolonization. Truman desegregated the army with an executive order in 1948. As the senate majority leader in the 1950s, Johnson is able to get the first civil rights bill through congress in 1957, and as president, under pressure from Martin Luther King, passes voting rights acts in 1964 and 1965.

This is when Barry Goldwater saw a chance to steal the Deep South from the Democrats by changing the party's stripes over civil rights to appeal to white southern Democrats - what Richard Nixon would later call the southern strategy, which sought, without embracing segregation directly, to capitalize on white resentment about racial integration by campaigning about racially coded issues such as a federalism, crime, and welfare.

After this, there are still some descendants of the progressive Republican tradition inaugurated by Theodore Roosevelt and embodied by New Englanders such as Prescott Bush and Francis Sargent, but by 1994 that movement was pretty much destroyed outside of New England. A good deal of the energy of the party since then is perhaps not driven by flat-out racism but by a burning resentment of things like affirmative action. Beginning in the Nixon administration, but especially the Reagan administration, there is a catering to working class white voters who believe Democrats are advancing black people at their expense. I think that is a driving force in Trump's electorate now.

So are there ways the modern GOP connects with ideals reminiscent of Lincoln’s?

Lincoln was a very business-friendly politician; you can make the case that his business-friendly politics are Republican politics now. Lincoln grew up in the Whig Party, a pro-business party that favored protective tariffs, industrial development, public improvements, higher education, and scientific agriculture. As a lawyer, he represented some major business clients like the Illinois Central Railroad. As president, he expected to bring about an economic transformation through public-private partnerships, such as the transcontinental railroad. But at the same time, the Whig Party, unlike the post-Civil War Republican Party, wasn't a free trade or laissez-faire party. Those were considered anti-capitalist positions, which is very different from today.

You mentioned that everybody claims they understand Lincoln. How do liberal and conservative scholars approach their understanding of Lincoln differently?

There is a lot of ferment on the right on the subject of Lincoln. If you look at scholarship now, liberal and conservative scholars of Lincoln fight about very different issues. Liberals fight about his development on views of race, how he grew from being a somewhat racist politician to becoming a champion of emancipation and possibly a champion of social and political equality of the races at his death. Liberals fight about that progress - exactly where he was when it started and where he was when he died. To what extent did he progress at all, and where would he have arrived had he not died when he did?

On the right, there are people who hate Lincoln because he was a centralizer. They see Lincoln as the creator of a powerful state – as America’s Bismarck – and they take strong exception to what they see as his redefinition of the American republic as well as to such things as his suppression of opposition newspapers and his suspension of habeas corpus. But there are also those on the right, Straussian theorists, who think of Lincoln's championship of the equality of man as a central instance of their attack on moral relativism. They see his opposition to slavery as an embrace of the individual’s ability to better his condition through free enterprise rather than an embrace of equality as itself a fundamental value. I think right of center you see fights between states’ rights conservatives and Straussians and they use Lincoln to club each other. The quarrels about Lincoln that go on the right and those that go on the left take place in almost complete isolation from each other.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences