Brandeis Nobel winners donate fruit fly sleep monitor to museum

Once a wall ornament at the entrance to Rosbash's lab, the monitor is now preserved in Stockholm for posterity

One of the Nobel Museum’s latest acquisitions? A contraption that measures the sleeping habits of fruit flies.

Professors Michael Rosbash and Jeff Hall donated the device, which was hand built at Brandeis, as part of a decade-old tradition of Nobel laureates bestowing an item of their choosing to the museum’s permanent exhibit. This week it took its place at Stockholm’s Nobel Museum beside Harvard economist Amartya Sen’s bicycle, Pakistani peace activist Malala’s headscarf and a silver platter from the movie, “The Remains of the Day.

The two scientists, in Sweden this week to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, used the apparatus in the 1980s when they undertook much of their groundbreaking research into the molecular mechanisms controlling circadian rhythms in fruit flies.

It remained in Hall’s office until the late 2000s when Brandeis demolished the building. Rosbash spotted it amidst the wreckage and hung it on a wall outside his lab in the Carl J. Shapiro Science Center. It will share display space at the Nobel Museum with the silver platter, a gift from this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature winner Kazuo Ishiguro, whose novel “The Remains of the Day” was the basis for the movie.

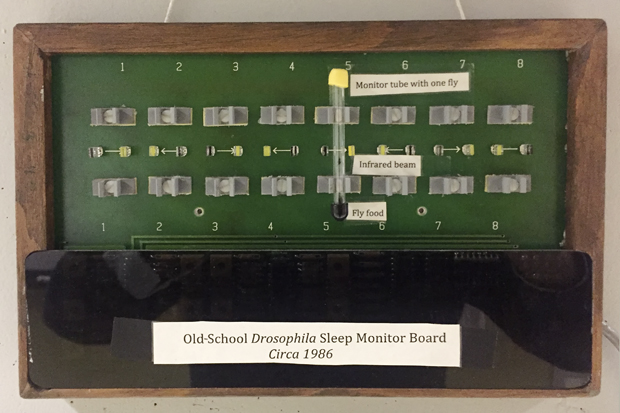

The fruit fly activity monitor enabled Rosbash and Hall to track the insects’ sleeping habits. They placed a fly inside a test tube and hitched it to the machine’s backing using brackets. An infrared red light shone across the middle of the test tube.

When the fly was awake, it flew around and broke the beam. When the insect was at rest, the infrared light remained undisturbed. The machine recorded the state of the beam for the duration of the experiment.

Rosbash and Hall compared the sleep schedule of normal and genetically mutated flies. If the schedule was irregular, it meant the gene they’d mutated was implicated in the timing of the fly’s rest and wakeful periods. Circadian rhythms drive the timing of sleep so the gene was clearly behind this larger set of physiological processes as well.

Much of Hall and Rosbash’s research focused on what was going on inside the cells of mutant flies with irregular circadian rhythms. By the mid-1990s, they’d identified many of the key molecular processes that determined the timing and duration of the fly’s physiological functions. They couldn’t have done it with the fruit fly activity monitor.

Categories: