What's the future of American Judaism?

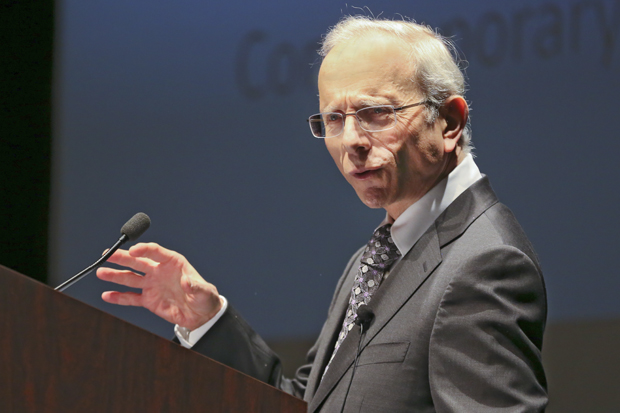

When it was published in 2004, historian Jonathan Sarna’s “American Judaism” quickly became the authoritative textbook on the subject. It won five awards, including the Jewish Book of the Year award from the Jewish Book Council, and was praised as “the single best description of American Judaism during its 350 years on American soil.”

Earlier this year, Yale University Press released the second edition of the book with a new introduction, conclusion, chronology

It brings the story of American Judaism up to the present, analyzing the latest demographic and societal trends and offering new insights concerning present-day and future developments.

“Jews witness two contradictory trends operating in their community: assimilation and revitalization,” Sarna writes in the book’s conclusion. “Which will predominate, and what the future holds, nobody knows. That will be determined day by day, community by community, Jew by Jew.”

BrandesNOW asked Sarna, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History and University Professor, about the new edition.

What prompted you to update the book now?

The world of American Judaism has changed a lot since I handed in my manuscript in 2002. I had a sense that it needed to be brought up to date, that there were themes that were not there, that there were developments that needed to be explained.

That whole movement in Jewish life has advanced with astonishing speed, perhaps not fast enough for those who live it, but

I tell the story of how AIDS really affected Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, which was New York’s first gay synagogue. In the 1980s, half of the congregation's males perished. And they wrote a prayer, an amazing prayer in 1984: “Our community is afflicted, and we know not why.”

I also obtained a picture of the first Jewish AIDS quilt, created by Beit Simchat Torah as part of its Names Project. Surrounding the names of those who died is the text of the Mourner’s Kaddish.

You also discuss the growing numbers of Jews of color.

In one generation, the idea that someone “looks Jewish” essentially disappears. There are a variety of reasons for that — conversion, adoption, intermarriage, the coming of Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews from Israel, and more.

Adoption plays a much larger role than most people realize. It used to be that adoptions most often took place within the Jewish community because the operative principle was that children and parents should “match.”

That idea disappeared in the 1980s and cross-cultural adoptions became more and more normative. One study suggests that 70 percent of all adoptions by Jews are now transracial. Those kids are growing up, so we are now seeing more and more Asian, African and Latin American children within a Jewish setting.

You point out another big trend — the decline of the Conservative movement. Membership has dropped by about 50 percent since 1970.

All over the United States, we see the decline of the broad middle in American religion. Mainline Protestantism has also declined. When you have a culture that's riven between right and left, the hardest place to be

Meanwhile, there’s been huge growth in the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

Chabad has risen in part, I think, because they offered an entirely new and disruptive model, welcoming everybody in and not asking for membership dues. In many

What can you tell us about American Jews’ changing views of Israel?

We have a younger generation that doesn't remember when Israel became independent in 1948, doesn't remember the Six Day War of 1967, and doesn't remember the great fear that accompanied the Yom Kippur War.

Instead, they only know a very strong Israel. They've heard story after story of how Israel is a dominant military power while several million Palestinian Arabs live as second-class citizens chafing under Israeli control. And if you're a member of a Jewish community that has long sympathized with the persecuted and the downtrodden, that new calculus proves unsettling.

Thanks to the internet and a lot of English language periodicals that represent a wide spectrum of views, American Jews are now much better acquainted with internal Israeli politics. Whereas before, they were simply mobilized in support of the Israeli government’s policies, today they mirror the range of opinions found within Israel itself. American Jews, however, are much more liberal politically than their Israeli counterparts. Forty-nine percent of American Jews characterize themselves as liberal but only 8 percent of Israelis do.

Is there a growing rift between Israeli and American Jews?

There are three different views on this question.

The first argues that, indeed, there is a growing rift. This “distancing hypothesis” is probably the consensus view among scholars and there's plenty of evidence to support it. The most worrisome evidence is a recent poll which asked young Jews whether it would be a great tragedy if the State of Israel were destroyed, and only about half of them said yes.

A second view is that nothing has really changed. There have always been opponents of Israel. Meanwhile, more and more Jews have gone on Birthright Israel trips and have a positive view of Israel, whether or not they support its current government. The so-called “distancing hypothesis,” according to this view, has been manufactured for political purposes.

The third argument is that young Jews are indeed more critical of Israel than older ones, but that is nothing new. Remember Mark Twain who once observed that his father was a remarkable man — “The older I get, the smarter he gets.” So it is with Israel, according to this view. The older we get, the smarter Israel gets.

I suspect that all three of these explanations are partially true. They’re not necessarily incompatible.

Of course, what everyone wants to know is will American Judaism survive?

I have tended to view American Judaism as cyclical, much like so many other religions in America. We are currently experiencing a national religious recession — many a synagogue and church is in decline — but remember that every past religious recession has been followed by a surprising religious revival, as young people rediscover religion’s power and benefits.

Someday, I expect, journalists will discover a surprising new interest on the part of young people in synagogues and religious life, and then the cycle will begin again.

That, of course, does not mean that the new synagogues will be identical with the old ones. We see lots of fascinating Jewish religious start-ups today — emergent congregations, partnership services, independent minyanim, and the like. Many of these start-ups will not survive, I suspect, but some of them will make it very, very big. They will reshape American Judaism in the decades to come.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences