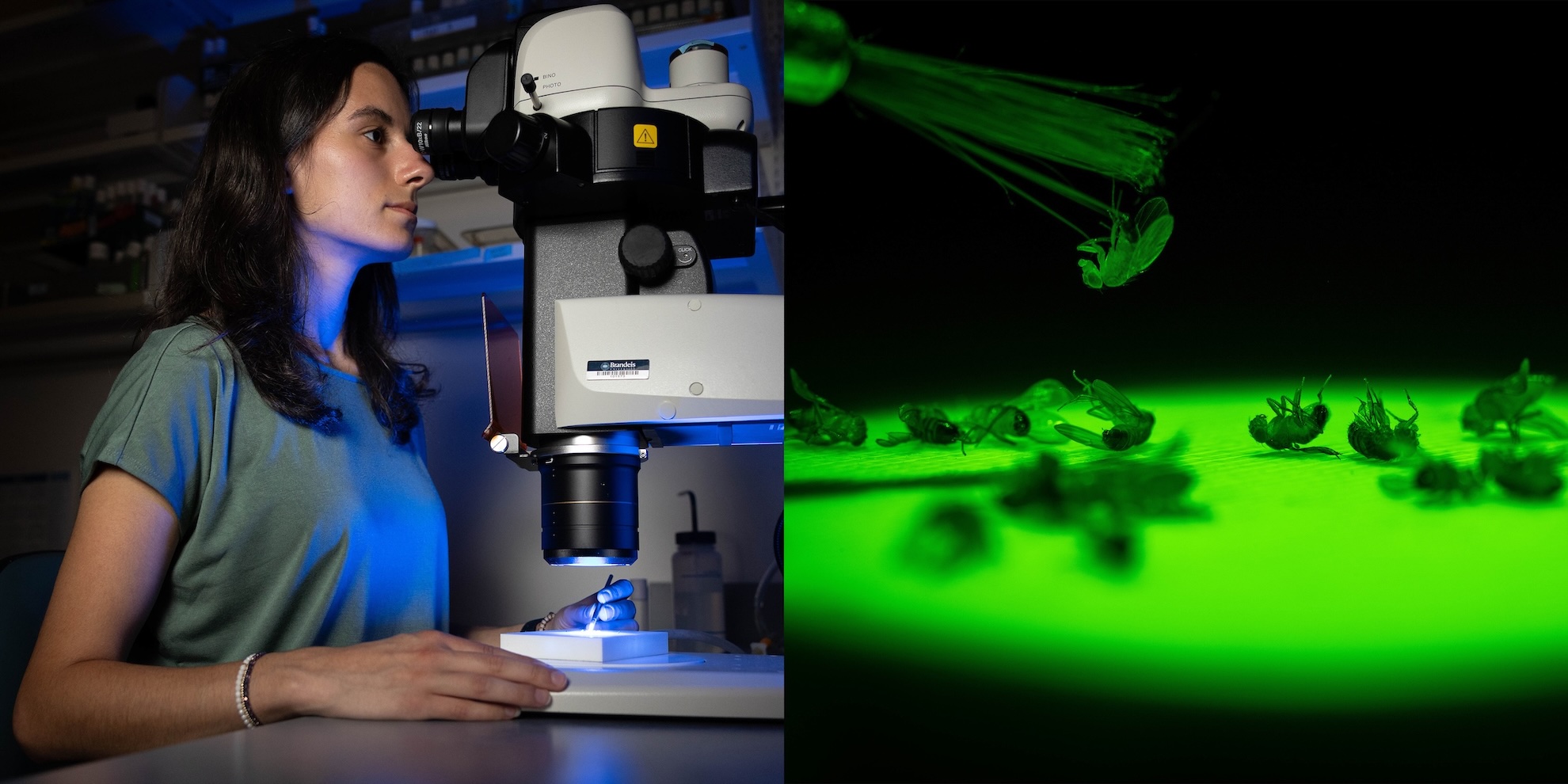

The fly whisperer

Photo Credit: Gaelen Morse

By David Levin

January 28, 2025

When Ava Towle ’26 started at Brandeis, she never expected to spend her time breeding and dissecting fruit flies. Yet her first experience as “fly flipper” — a lab assistant that keeps fly stocks alive — helped spark a lasting passion for hands-on research

“When I started working in the lab my freshman year, I didn't entirely know what I was getting myself into, but I fell in love with it really quickly.”

Today, as an undergraduate researcher in biologist Paul Garrity’s lab, Towle studies the intricate cell biology that lets insects feel changes in temperature. Each fly’s antennae, she says, hold neurons that can sense heating or cooling. Exactly how they do that isn’t yet clear, however. Towle thinks a class of proteins called GPCRs may be involved.

Towle says it’s not yet clear if they’re a linchpin in the cells’ ability to sense their surroundings, but she’s chipping away at the question. Using the gene editing tool CRISPR, she’s able to breed designer flies that lack different kinds of GPCRs in their neurons, and then test the insects to see if their behavior changes as a result.

“The flies are introduced into a space that’s room temperature on one side, and relatively cool on the other side. Normally, you would expect them to spend all of their time on the room- temperature side, because that's their preferred temperature,” she says.

Flies without certain GPCRs, however, seem to spend equal amounts of time on both sides, meaning that they can’t sense the difference in temperature. By repeating this experiment with different genetically modified flies, Towle is revealing whether specific GPCRs are critical for sensing changes in temperature. Her findings could have real-world applications — many disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes are attracted to body heat, and blocking their ability to sense temperature could be an effective way to keep them from biting and infecting humans.

That end goal isn’t what drives Towle, however. For her, being able to do independent research as an undergraduate — and answer fundamental questions about how cells work — is itself empowering.

“I’ll do an experiment, and then I’ll go home and I can't stop thinking about it,” she says. “It’s really cool. I feel so lucky to be able to experience that; to be able to take ownership of my own project, and to be around other people in our lab who are passionate about their work. It’s an opportunity that I probably wouldn’t have at any other school.”