Ha Jin, PhD'93, reflects on his new beginning at Brandeis

The acclaimed author talks, and writes, about the barriers and advantages of starting over in America

Ha Jin, PhD'93, on campus for a 2004 'Meet the Author' event

Over the last two decades, Ha Jin has become one of America’s most celebrated writers. His stories and novels have received the PEN/Hemingway Prize, the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, the National Book Award, the Pushcart Prize, and his work has been selected for the annual series “The Best American Short Stories.” He also joins Philip Roth, John Edgar Wideman and E.L. Doctorow as the only two-time winners of the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Jin’s long list of literary accomplishments is even more impressive, though, when you consider that the language he’s writing in- English- is not his native tongue.

“The most difficult part in writing in this language is uncertainty,” Jin told BrandeisNOW during a recent interview. “I am not sure how far I can go, and I might fail at any moment. But uncertainty is human condition, which I have learned to accept.”

Jin faced such uncertainty 20 years ago, while he was at Brandeis studying for his doctorate in English and American Literature. When he arrived on campus in 1985, it was Jin’s first time in America, and he planned to return home to China after earning his degree; he even had a teaching job lined up at Shandong University. But things changed when the Tiananmen Square protests erupted in 1989, and television screens around the world were filled with images of violent clashes between students and Chinese troops.

“At the time, all the schools and universities were owned by the state in China. I just couldn’t do it. I wouldn’t serve a state like that,” Jin said. “And also, a few weeks later, my son arrived. I realized that he would become an American.”

Just as his life in America was beginning at Brandeis, so too, was Jin’s writing career. While he had written some poetry back in China, Jin was unpublished before he came to campus. His dissertation advisers, the poets Allen Grossman and Frank Bidart, saw his potential, and encouraged him to seriously pursue writing outside of his academic work.

“Allen Grossman always said to me, for you, writing must come first,” Jin remembered. “That was very, very unusual for a scholar to say that.”

With Grossman and Bidart’s guidance, Jin began to find success in literary journals. In an introduction to some of his early poems that were published in the Boston Review, Grossman wrote: “We hear in these poems the living and the dead- vulnerable, passionate, rational, unforgiving, heartbroken, relentless, gay- speaking of the interests which constitute their humanity in an uncanny language in which English is carried up into a region of pure human authenticity- the language of no nation but the nation of the person who speaks willingly or unwillingly the truth.”

Jin's decision to write exclusively in English was not an easy one, as he explained in a May 2009 New York Times op-ed: “It took me almost a year to decide to follow the road of Conrad and Nabokov and write in a language that was not my own," he reflected. "Yet if I wrote in Chinese, my audience would be in China and I would therefore have to publish there and be at the mercy of its censorship. To preserve the integrity of my work, I had no choice but to write in English.”

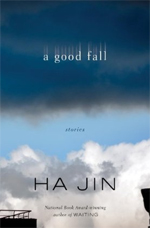

Language, and the barriers presented by it, plays a role in many of the stories from Jin’s latest collection, “A Good Fall.” It focuses on Chinese immigrants, living in Flushing, N.Y., who are separated on multiple levels from their homeland; this gap is opened, in part, by language. In the title story, a former Buddhist monk, struggling to find work because he can’t speak English, tries to kill himself by jumping off a building. In “Children as Enemies,” a grandfather becomes deeply upset when his grandchildren want to change their names to sound more “American.” Jin’s characters are caught in a cultural transition, and their speech, often interlaced with cumbersome English phrases that are derived from Chinese sayings, reflects it.

Language, and the barriers presented by it, plays a role in many of the stories from Jin’s latest collection, “A Good Fall.” It focuses on Chinese immigrants, living in Flushing, N.Y., who are separated on multiple levels from their homeland; this gap is opened, in part, by language. In the title story, a former Buddhist monk, struggling to find work because he can’t speak English, tries to kill himself by jumping off a building. In “Children as Enemies,” a grandfather becomes deeply upset when his grandchildren want to change their names to sound more “American.” Jin’s characters are caught in a cultural transition, and their speech, often interlaced with cumbersome English phrases that are derived from Chinese sayings, reflects it.

“I want the language to be slightly foreign, but absolutely accessible,” Jin explained. “In other words, not be bookish. On one hand it is kind of a big problem. On the other hand, it’s an opportunity as well, because there is kind of a space between two languages in which a writer can use for creative purposes.”

This sticky melding of cultures also forms the plot of one of Jin’s most acclaimed earlier stories, “After Cowboy Chicken Came to Town,” which centers on workers at an American fast food franchise that has recently opened in a small Chinese town. Some of the restaurant’s policies- specifically the burning of uneaten chicken at the end of the day- ruffles many of the employees’ feathers.

The story was conceived, Jin says, when he was a student at Brandeis and read in a Chinese newspaper that an American fast-food franchise in Beijing would burn its daily leftovers. The characters in “Cowboy Chicken” stage a protest, but the move backfires. When the story closes, though, the fight is far from over. As Jin’s narrator says, “This was just the beginning.”

For an author who’s own new beginning began at Brandeis 20 years ago, Ha Jin’s American story has turned out to be a good one.