Dr. Angela Brodie receives 2010 Gabbay Award

Cancer research pioneer credited with saving lives

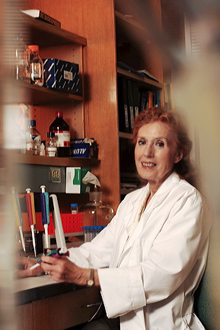

Dr. Angela Brodie

An award ceremony was held Tuesday evening, October 12, for the woman who pioneered a new class of drugs for women with breast cancer.

Professor Angela H. Brodie is the recipient of the 2010 Jacob Heskel Gabbay Award in Biotechnology and Medicine.

She was honored for her groundbreaking research in the development of aromatase inhibitors, which combat the return of cancer in postmenopausal women by reducing the level of estrogen produced by the body, since estrogen is a major stimulus of breast cancer.

Brodie is professor of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center.

Before the dinner, Brodie delivered a lecture on “Aromatase Inhibitors and Breast Cancer: Concept to Clinic” to about 100 people. That evening, Brodie was guest of honor at the award dinner at the Faculty Club, where she was presented with the $15,000 prize and a medal.

At the dinner, Myrna Gabbay, whose family foundation supports the Gabbay Award, spoke of her own battle with breast cancer and how Dr. Brodie’s work, bringing laboratory breakthroughs, “from bench to bedside”, has helped save her life and the lives of and thousands of other women.

After-dinner remarks were presented by Dr. Robert A. Weinberg of MIT, one of the nation’s foremost cancer researchers. He spoke about the on-going problems encountered in the war against cancer, and concluded with his own appreciation of the life-saving work that has been carried out by Dr. Brodie and her team.

Brodie’s discovery of aromatase inhibitors, now widely used to combat cancer, came after decades of research that began in Massachusetts when she came from her native United Kingdom to the Worcester Foundation on a one-year postdoctorate sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. It was the 1970s, and the Worcester Foundation was in the midst of developing the oral contraceptive pill.

“It was a very exciting time,” says Brodie. “From my work at the cancer hospital in Britain, I got very interested in breast cancer.” Brodie stayed on beyond the fellowship, married, and worked side by side in the lab with her husband, an organic chemist, who helped in the early stages of research before he took a post with the National Institutes of Health.

In 1979 Brodie moved to the University of Maryland with a lot of data that looked like it had potential. “Drug companies were not interested then,” she said, but that changed after she conducted clinical trials, collaborating with oncologists, in around 1982. “Then we were able to get companies involved.”

Since then, she says, “quite a lot of drug companies got into making compounds similar to ours. Since they’ve been using them…it’s become evident that they are effective. They have been the first line treatment for decades.”

Brodie says she hears from women whose lives have been saved, including a piano teacher of one of her students, and colleagues on campus.

Brodie is not resting on her laurels, though. While her discovery has saved countless lives, she is haunted by the fact that some breast cancer tumors are resistant to the treatment she pioneered. “There are still patients that do not respond, and we’ve been doing some current research to try to improve treatments for those patients. We’re trying to figure out the resistance, so we can try to develop new drugs to block the resistant pathways.”

Her lab is now looking ahead at two main problems: tumors that have become resistant to treatment, and tumors that lack receptors altogether. Animal studies show promise and she hopes to replicate results in human trials now open in Chicago and in Maryland. “With patients who have taken first line aromatase and have become unresponsive and the disease progresses, we can give them a cocktail of combined treatments,” she says. One drug aims to block the resistant pathways, so the second drug, her aromatase inhibitor, can do its work.

The Gabbay Award ceremony Tuesday was far from the first time Brodie’s contributions to cancer research have been recognized. In 2005 she was the first woman to receive the prestigious Charles F. Kettering Prize for cancer research, one of three granted annually, which came with a $250,000 reward, and in 2006 was awarded the Dorothy P. Landon-AACR Prize for Translational Cancer Research.

The Gabbay Award at Brandeis was established in 1998. It recognizes outstanding strides in basic and applied biomedical sciences. Its administrators note that “most scientific revolutions are sparked by advances in practical areas such as instrumentation and techniques.”

The Gabbay Foundation’s association with Brandeis began in the 1990s, according to Biochemistry Professor Dagmar Ringe. She says that she, colleague Gregory Petsko, professor of biochemistry and chemistry and Kenneth Gabbay, professor of Pediatrics and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Pediatrics, Molecular Diabetes and Metabolism at Baylor College of Medicine, conducted research together while Gabbay was visiting Brandeis on a one-year sabbatical. Back then, according to Ringe, Gabbay was asked to serve on a campus committee that promoted “tech transfer”, finding practical applications for academic technology. Gabbay’s interest in tech transfer, according to Ringe, prompted his family’s foundation to fund the Gabbay Award and to ask Brandeis’ Rosenstiel Basic Medical Sciences Research Center, where Ringe and Petsko currently work, to administer it.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology