Long-forgotten recording of Bob Dylan's Brandeis folk festival performance to be released

Alum reflects on 1963 show, collector shares how tape was discovered

Bob Dylan performing in the early 1960s.

It's the record that almost wasn't.

Two weeks before the release of his 1963 sophomore album, "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan," made the musician an icon, he was scheduled to appear at Brandeis University's now gone Ullman Ampitheatre.

|

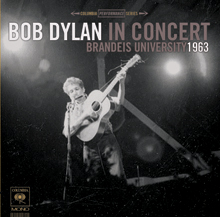

| On April 12, "Bob Dylan in Concert – Brandeis University 1963" will be released. |

Mother Nature had other plans. It was May 10, but New England's unpredictable weather brought snow to the north, while lightning storms hovered over Massachusetts. Bolts hit transformers, sparking fires and leaving at least a few areas of Greater Boston without power.

At Brandeis, the impact was apparently less severe, but organizers changed venues for the university's first folk festival. The concert was held in the gym, and unbeknownst to Dylan and generations of fans, his seven-song set was recorded.

Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings will release that recently-discovered recording, "Bob Dylan in Concert–Brandeis University 1963," on April 12. A limited edition was first made available last year with Amazon purchases of "The Bootleg Series, Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos."

The tape is significant because "most live recordings of Bob are bootlegs. We weren't familiar with this recording," says Jeff Rosen, Dylan's longtime manager.

The recording was discovered by Jeff Gold of recordmecca.com in Ralph Gleason's massive basement collection of music and related memorabilia. Gleason was the first fulltime jazz and pop critic at an American newspaper, and was co-founder of Rolling Stone magazine. He was early to recognize the significance of Dylan, Lenny Bruce and Miles Davis, and was close to many of the musicians of the 1960s and 1970s.

After his death in 1975, his family preserved what Gold describes on his blog as "a vast archive of records, magazines, newspapers, posters, press materials and all kinds of ephemera," much of which his son, Toby, eventually sold.

Among many others, a tape with a lightly penciled "Dylan Brandeis" label, which took some time for him to decipher, caught Gold's attention. Toby Gleason allowed him to take it home and rent equipment to listen and digitalize the recording to determine whether it was a known bootleg. It wasn't.

"It took me only 30 seconds to realize that this was something big. It was obviously professionally recorded, in stereo, and the performance and sound were both excellent," Gold says, guessing perhaps a Brandeis-sanctioned recording was given to Dylan's management that night and eventually passed on to Gleason. "I think part of what makes it special is that Dylan is not yet a star; he's a promising young folksinger with a new batch of songs, none released at that point, playing a slot in a low-profile college folk festival."

Despite potentially higher bidders, Gold called Rosen and they and Gleason quickly struck a deal for the folk festival recording.

Arnie Reisman '64 was a junior back then, and co-editor in chief of the student newspaper The Justice, which was a sponsor of the event. That meant he had a hand in planning the weeklong festival.

Reisman recalls sitting that night in The Justice – housed in the basement of Mailman Hall, which was on the current site of the Office of Admissions – when someone brought the 21-year-old Dylan in for a quick meeting before soundcheck.

"He was a piece of work then, a bit of a crab," says Reisman, who added that Dylan was concerned that the equipment be appropriately set up. After all these years, it's the technology that Reisman remembers best.

"There was a tape being done by the university. From what I recall, there was only one tape recorder that was patched into the microphone," he says. "There could have been someone in the audience recording it, but it would have sounded hollow and a million miles away."

The audio technician had momentarily walked away just prior to Dylan's performance, so Ralph Norman, The Justice's photographer, was asked to step in.

"Ralph was there pushing the button," Reisman says, wondering how the tape wound up in the record company's hands. He has some theories.

To book Dylan for the show, Reisman and his classmates had worked with Manny Greenhill of Folklore Productions, which then had an office in Boston. Greenhill was a "folk, blues music entrepreneur, impresario, booker of everybody, agent of everybody" whom, current Folklore staff confirms, generally kept archived tapes of all his musicians' performances. Several acts he represented were on the bill that week, including Pete Seeger, Jesse Fuller, and Jean Redpath.

"[Dylan] was considered a local hero since he played all the clubs in Cambridge, [Mass.]. Everybody was aware that [we] were a little head of the curve," Reisman says. "He was at the cusp of turning a lot of people around to listen to his type of music."

Though Dylan was well-known to Boston-area students, he wasn't difficult to secure for the festival. He again played at Brandeis during the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue tour.

"He's clearly enjoying himself, bantering with the crowd, and while he's at the top of his game, he doesn't seem to be feeling any pressure," Gold says of Dylan's festival performance. "But it's the calm before the storm - his career is about to take off in a way no one could possibly have anticipated. He's about to become BOB DYLAN."

The recording includes: "Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance" (incomplete), "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues," "The Ballad of Hollis Brown," "Masters of War," "Talkin' World War Three Blues," "Bob Dylan's Dream," and "Talkin' Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues."

Categories: Arts, Student Life