Growing cohort of women in science calling Brandeis home

'It's a welcoming place,' says Division of Science Chair Eve Marder '68

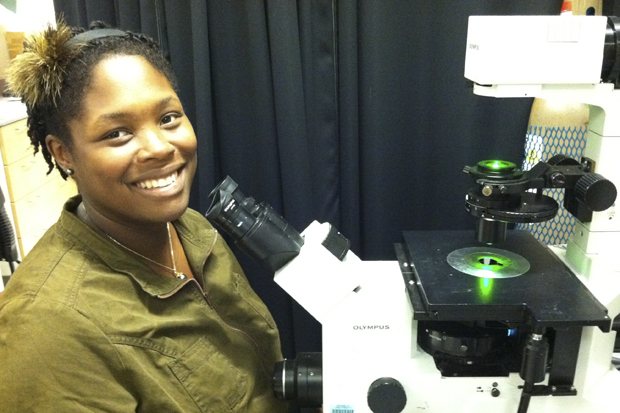

Mareshia Donald peers into a microscope in the Birren Lab, examining heart cells that have been co-cultured with neurons. She’s researching sympathetic nervous system connections, the points of communication that allow the body to perform involuntary functions like breathing, pupil dilation and, in the case of her research, the beating of the heart.

Results of her research could lead to strategies for correcting problems following pediatric cardiac surgery.

Donald is one of what administrators and senior professors say is a talented and growing cohort of women in neuroscience, biology and physics, fields in which Brandeis has an outstanding reputation and record of accomplishment. Since its founding Brandeis has made a concerted effort to recruit and maintain female faculty in the sciences. While numbers of women have been growing strongly in biology and psychology, women still lag behind their male counterparts in many other scientific fields such as physics and math.

What exactly are women in science up against nationally and on campus, and what is Brandeis doing to provide a supportive community?

“It’s a welcoming place,” says Eve Marder, chair of the Division of Science and past president of the Society for Neuroscience. Marder received her undergraduate degree from Brandeis in ‘69 and returned in ’78 as an assistant professor. Her research in the field of circuit function and the properties of neurons and their synaptic connections is world renown.

“We’re successful in attracting women not only because of the strong work that we’re doing, but because women feel comfortable when they come to interview,” says Marder. “If a young female physicist meets three young female physicists on the faculty who are thriving, it’s a natural selling point.”

Marder partially attributes the success rate to women who blazed the trail, people like Kalpana White, professor emerita of biology and neuroscience, who recently retired.

“She was very calming, balanced and grounded,” says Marder of White. “As the two of us flourished, it helped create a healthy atmosphere.”

According to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences report, published in February 2011, women have made dramatic gains in science since 1970. Today, half of all M.D. degrees and 52 percent of Ph.D.s in life sciences are awarded to women, as are 57 percent of Ph.D.s in social sciences, 71 percent of Ph.D.s to psychologists and 77 percent of D.V.M.s to veterinarians. Forty years ago, they say, women’s presence in most of these fields was dramatically lower. In 1970 only 13 percent of Ph.Ds. in life sciences went to women.

In the most math-intensive fields, the report found that growth in the number of women has been less pronounced.

“I think that there are a few reasons that account for this,” says Ruth Charney, who was one of two female professors of mathematics when she arrived at Brandeis in 2003. “One is that women seem to be attracted to things that directly affect people and less to the more abstract; it’s not a question of hard or easy, but a question of what you’re going to spend your time thinking about.”

Charney says that, considering the relatively low numbers of women applying to math programs, the fact that one-third of the graduate students in mathematics at Brandeis are women is good. But she cautions the university not to feel that things are wonderful and that extra effort is no longer needed.

“Everything isn’t all right,” says Charney, who is slated to be the next president of the Association of Women in Mathematics, an international organization that encourages careers in the mathematical sciences.

“For years most of the top 10 schools had no women, then they all had one,” says Charney. “It’s only very recently that you’re starting to see the top schools look a little more distributed, but it’s slow work.”

Another pioneer on campus is Bulbul Chakraborty, the Enid and Nate Ancell professor of physics, who came to Brandeis as an assistant professor in 1989. She, too, was the first woman in her department, which was started in the early 1960s. Chakraborty is an esteemed theorist with a focus in the area of granular materials.

“We have four women faculty out of 18, which is huge,” says Chakraborty. “The national average is less than 10 percent and Brandeis has 20 percent. That is very significant.”

Chakraborty says that although her male colleagues at Brandeis were much more welcoming of women than was her experience elsewhere, in the early years she had no women to talk to in physics.

Two years ago, at the urging of James Mandrell, chair of the Women and Gender Studies Program, Charney, Chakraborty and Mandrell founded the Women in Science Initiative, which brings together graduate students, post doctorates and faculty to share ideas, concerns and offer support in areas such as research and work-life balance.

Donald, who is an active member of the Women in Science Initiative, says that graduate and post-doctoral students have different needs than faculty members and saw the Women in Science Initiative as an opportunity not only to foster relationships, but help address issues that weren't being met. One in particular is a policy regarding parental or family leave for graduate or post-doctoral fellows.

“MIT has a policy. Harvard has a policy. We compete with these universities for students and postdoctoral fellows but we're not competing with them where policy for parental and family care leave for grad students and postdocs is concerned,” says Donald.

Other topics of concern include maternity leave and lactation space for breastfeeding. Under the new healthcare law, workplaces with more than 50 employees must provide lactation space, but graduate and post-doctoral students do not qualify as employees. While this has not been formally resolved, Donald says that a number of faculty members worked to secure two private rooms on campus in which to express breast milk.

Maternity leave for graduate students can be complicated because their compensation often comes from a mix of foundation and government sources as well at the university.

“My training at Brandeis is teaching me to think critically, broaden my scientific understanding and develop my leadership skills,” says Donald. “As long as women continue to perform their traditional roles in addition to pursue professional endeavors, we will be faced with challenges and tough choices. I think success will come by learning through these challenges and using what we've learned to become better at what we do in life and in our fields of study."

Susan Birren, dean of Brandeis' College of Arts and Sciences and a professor of biology and neuroscience, says it’s important that every women scientist be in a work situation in which they feel comfortable and valued and that they have what they need to be successful as a scientist.

“We’re interested in understanding what we’re doing well and where there’s room for improvement,” says Birren, who was hired as an assistant professor in 1994. “When I came in as an assistant professor there were many senior women faculty members who engaged in mentoring relationships and that was huge.”

A decade earlier, when Birren entered graduate school, she recalls feeling as if there were different generations of women.

“The oldest generations essentially did their science and were professors,” says Birren. “They didn’t have families and often were not married. Obviously there were exceptions to this.”

Then, she says, came a generation of women who were married, but often did not have children.

“The women of my generation are integrating many things,” says Birren. “The question that I often get from young women scientists is: How do you manage to have a family and still be a scientist?”

The answer, Birren says, is making decisions about how you’re going to spend your time.

“Brandeis prides itself on social justice and takes it seriously internally as well as externally,” says Birren. “Some of these are tough problems, but I think that as an institution the new administration is very committed to figuring out ways to make this a welcoming place for many different types of people.”

Gina Turrigiano, a professor of biology whose lab focuses on how neurons and circuits in the brain maintain stability, started at Brandeis as a post-doctoral student in Marder’s lab in 1990. She has won numerous awards including the McArthur Foundation Fellowship; the National Institutes of Health Director’s Pioneer Award

and most recently the 2012 Nakasone Award for her research on homeostatic plasticity in the nervous system.

One of the reasons that Turrigiano says she chose Brandeis was to have female mentors.

“I came from University of California, San Diego, where the number of women faculty members in neuroscience was abysmal,” says Turrigiano. “At that point there were 70 to 90 neuroscientists, of whom three or four were women.”

Turrigiano became a faculty member at Brandeis in 1994. She says that she’s gotten used the environment at Brandeis; the number of female colleagues, the degree of supportiveness in her department for junior faculty and the flexibility in dealing with kids and life problems.

“It’s surprising to me when I go to other institutions and realize that it’s still not the case,” says Turrigiano. “I see Brandeis as the future of where biology is going, but we go there faster.”

Categories: Research, Science and Technology