Ancient cities destroyed by modern madness

Professor Tzvi Abusch discusses the Islamic State’s rampage in Northern Iraq

A meeting hall in the Shrine of Hatra, destroyed by ISIS

Tzvi Abusch, the Rose B. and Joseph Cohen Professor of Assyriology and Ancient Near Eastern Religion, has spent his career studying ancient Assyrian and Babylonian texts, precious relics of a civilization whose sites are now being systematically destroyed by the so-called Islamic State, known as ISIS.

The destruction is part of the Islamic State’s propaganda campaign to erase all pre-Islamic history from the region and, likely, fund the organization through black market antiquity sales.

To date, militants in Northern Iraq have bulldozed the ancient cities of Nimrud and Hatra, a UNESCO World Heritage site; blown up the Tomb of Jonah outside Mosul, and ransacked the Mosul Museum, destroying or looting hundreds of artifacts. Now, they’re threatening to destroy Nineveh, the site of one of the greatest libraries of antiquity, and some reports suggest militants have already succeeded in bringing down parts of its ancient walls.

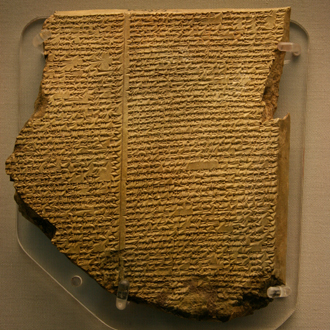

Nineveh has been occupied since 7,000 B.C.E. and contains thousands of clay tablets, including the Epic of Gilgamesh. Abusch has spent much of his life researching, translating and writing about these tablets.

|

| Part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, found in Nineveh |

BN: This isn’t the first time these cities have been attacked in their long histories. How does ISIS’ campaign compare to earlier invasions and pillages?

TA: In the ancient world, looting was part of conquest. Conquerors would often take statues from the conquered city, and the conquered perceived this as the abandonment of their gods and as the loss of their divine protection. When the Elamites sacked Babylonia, they took the stele containing Hammurabi’s Code, one of the most important legal and ideological writings from the ancient world, back to their capital, Susa. They erased a section of the stele but didn’t destroy it. Certainly there was symbolic destruction as a cultural phenomenon in the ancient world.

BN: Many of these sites have been excavated continually since the 1800s. In one sense, are we lucky that the sites being destroyed are so well studied?

|

| Portal guardians mark the entrance to what once was the Northwest palace in Nimrud |

TA: There is so much more work to be done. Archaeologists of the 19th and 20th centuries were preoccupied with the monumental architecture and the acropolises in the center of cities, and, as a result, we still don’t know a lot about how ordinary Mesopotamians lived. There are still tablets to be found. Every tablet lost could hold the next Epic of Gilgamesh.

BN: Why should the average person care about the destruction of archaeological sites?

TA: These are the oldest cultures, the oldest cities on Earth. They are older than ancient Egypt. We know more about Mesopotamia than we know about ancient Europe before 1700 B.C.E. As humans, much of our identity lies in our past. To destroy this culture is to destroy our past.

BN: What about you? You’ve been studying this ancient culture your entire career. What is it like to watch it being destroyed?

TA: These texts populate my world — in many ways, they’re my friends. It’s a great, great loss.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences, International Affairs