The winter of 1933: when the world turned back toward war

Photo/public domain

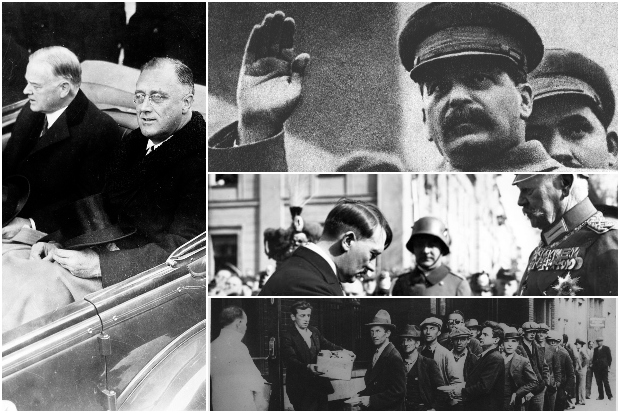

Photo/public domainLeft: FDR at his 1933 inauguration. Top right: Joseph Stalin, 1933. Center right: Adolf Hitler, 1933. Bottom right: Food line in New York City, 1932.

The political winds were shifting in the winter of 1933. Nations began to turn inward, toward nationalism and isolationism. And the world edged closer to war again.

Professor Paul Jankowski’s new book, “All Against All: The Long Winter of 1933 and the Origins of the Second World War” (HarperCollins, 2020), chronicles this critical time in world history.

Jankowski, the Raymond Ginger Professor of History, discussed “All Against All” with BrandeisNow.

Why did you focus on this one winter?

Jankowski: This particular time in history was a critical moment. The world was fragmenting, countries were turning away from one another, and against the whole idea of a world order and international cooperation.

What were some of the key events in 1932-33 that began to bring the world closer to war?

Jankowski: A number of things happened that probably did not seem to bear much relation to one another at the time. But in hindsight, they most obviously did. In the 1920s, there was an attempt at a new world order based on the League of Nations and collective security, and free trade and supposedly national self-determination. All of that began to fall apart by the early 1930s.

Hitler came to power in January 1933, and Japan left the League of Nations that winter. Both of these were significant, intensely nationalistic events, full of “go it alone” sentiment.

The Italians continued to develop earlier plans to invade Abyssinia, now Ethiopia. The Soviet Union’s five year plan — forced industrialization involving enormous sacrifice and suffering — was proceeding apace.

In the United States, the election and inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt played a part in these developments. Like his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, FDR did not want the U.S. to become entangled in any kind of world order. He certainly wasn't going to risk his domestic recovery program on commitments abroad.

What role did the Great Depression play?

Jankowski: It did play a part, but it was far from the sole factor. The idea of American isolationism didn't wait for a world economic depression to announce itself; it was already ascendant in the 1920s even if it wasn’t acted out on the world stage.

In Germany, long before the 1929 stock market crash, a large swath of the population believed their nation had long been a victim of the world order, and that it had nothing more to expect from the rest of the world.

The global economic depression had a very powerful effect in accentuating nationalist sentiment in various countries, but it wasn't responsible for it. This mentality, in my view, can lie dormant. It's there, it's latent, and it can spring to life depending on the circumstances.

How did the outcome of the First World War influence the rise of nationalism and isolationism?

Jankowski: The First World War bred nothing but unhappiness. It yielded embitterment and discontent among the victors, not to mention the losers.

Both the individuals who fought and the nations that were involved believed their victories had been thrown away, or that they had somehow been swindled, or had suffered in some other way.

I call it the nationalization of resentment. It ennobles the suffering of individuals. It's a very, very tempting message for leaders and demagogues to convey. During the winter of 1932-33, in the midst of a world economic depression and lingering dissatisfaction with the outcome of the First World War, no leader wanted to preach internationalism; it was too dangerous a message.

Was this ‘nationalization of resentment’ exploited by specific leaders or countries?

Jankowski: It's not necessarily a right wing or a fascist message, and it's conveyed in many different ways.

Hitler always presented himself as the victim — an ordinary German soldier, a victim of the First World War. But there are many ways of nationalizing resentment.

After Hoover’s initial reaction to the 1929 stock market crash, which was actually quite vigorous, he took to blaming the country’s economic problems on the world at large, arguing that the world depression that developed was really beyond his power — it wasn't his fault. The nationalization of resentment enabled people to identify their individual plight with that of their country and to recognize the speaker as a kindred spirit.

When he justified the five year plans, Stalin presented them in the context that Russia had always been victimized by more advanced countries, and would be again if they were not ready for war.

Roosevelt in the 1932 election said nothing about foreign affairs at a time when the Nazi Party had reached its peak in Germany. He knew it was not what his listeners and prospective voters wanted to hear about. He knew that he needed their support for his domestic recovery program.

How does nationalism in the early 1930s compare to earlier such movements?

Jankowski: In the 19th century, most nationalism was directed against another country. The Polish against the Russians, or the Irish against the English, and so on. The kind of nationalism we saw in the early 1930s basically regarded the world as hostile, and it assumed the form of isolationism or expansionism, among other forms.

In 1933, Germany, Italy, Russia, Japan, the U.S. and other countries began following their own way, guided by different national myths and national postures, but there was a kind of nationalism abroad here, which I think is distinctive.

Are there apt comparisons between what happened in 1932-33 and today?

Jankowski: This belief that the world is a hostile place and that the nation is a sanctuary against the rest of the world bears some resemblance to today, and the turning away from an attempted world order, I think, is a valid parallel.

In our own day, there was a post-Cold War attempt at a new U.S.-led world order based on free trade, globalization and human rights. In recent years we've seen that effort fall apart, and prove about as elusive and short-lived as the new world order that was supposed to follow the First World War.

The perception of the world as hostile has certainly turned up in various ways in the past 10 years. It is obvious in the Brexit movement in Britain and in other movements all over Europe, even though they've met resistance. It's been obvious as well in some of the developments in East Asia. And it is very obvious to me, in the kind of chaotic, impulsive approach to foreign policy that President Trump betrays.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences, Research