Could the Jewish vote decide the election?

These are the places Jewish voters could swing the election

Courtesy/Steinhardt Social Research Institute

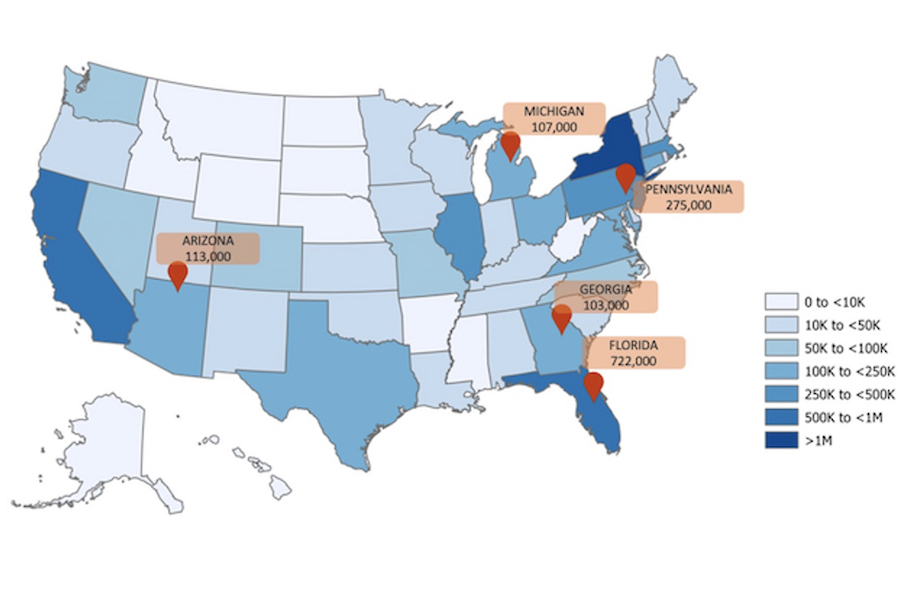

Courtesy/Steinhardt Social Research Institute A map showing the distribution of the Jewish electorate across the country. (A Jewish voter is defined as an adult 18 or older who identifies their religion as Judaism or considers themselves Jewish in some other way, such as ethnically or culturally.)

In the run-up to the presidential election, BrandeisNOW asked faculty to provide analysis and insight into some of the most pressing issues facing the country. This story is part of the series.

If the 2020 presidential election is anything like 2016, it will be decided by a relatively small number of voters in a handful of battleground states. American Jews, who comprise less than 2.5% of the population, are small in number. Nevertheless, as the political upset in 2016 has made clear, every vote matters.

Historically, Jewish adults vote at rates higher than the national average, with some estimates putting the rate between 80 to 85%.

Because of their concentration in a few states and their relative homogeneity in political outlook, Jewish voters are an important part of the electoral math, especially in states or districts that are considered competitive.

In our research, we use Bayesian Multilevel Regression with Poststratification to synthesize data from hundreds of national surveys to develop profiles of the US Jewish population that include their geographic and demographic distributions. Our most recent work was a synthesis that included data from over 1.3 million US adults to provide Jewish population estimates within US congressional districts.

Fifteen states are each home to 100,000 or more Jewish adults (see map above). Jews are concentrated in the coastal states, with New York and California alone having more than 2 million Jewish adults. Both of these states are Democratic strongholds and rated as “solid Democrat” in the presidential race.

Nearly 1.5 million Jewish adults, however, live in a handful of states that are critical to the electoral college vote and/or senatorial contests. These states include Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. In these competitive states, higher rates of voter turnout or greater support for the Democratic Party could make a critical difference in the outcome.

In Michigan, for example, which is home to an estimated 107,000 Jewish adults, President Trump won the state’s 16 electoral college votes in 2016 by with fewer than 11,000 votes.

In Florida, where fewer than 600 votes separated Bush and Gore in the 2000 US presidential election, there are 722,000 Jewish adults (over 4% of the state’s adult population). And in Pennsylvania, where Trump won in 2016 by a margin of less than 45,000 votes (out of more than 6,000,000), there are nearly 275,000 Jewish adults (nearly 3% of the population).

In other states, in particular Arizona and Georgia, which may determine control of the Senate, enthusiastic Jewish voters turning out at historically high rates could have a similar potential to change the electoral outcome.

This presidential election, perhaps more than any other in modern history, has the potential to influence not just the direction of US domestic and foreign policy, but the very foundation on which the country was built. Efforts to mobilize voters in battleground states, alongside targeted strategies by both parties to motivate voters in key demographic groups, have the potential to change the electoral outcome. As campaigns and parties strive to engage with Jewish voters in meaningful ways that extend beyond their turnout numbers, they have an opportunity to understand the diverse range of issues that are important to them.

Leonard Saxe is the Klutznick Professor of Contemporary Jewish Studies and director of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies and Steinhardt Social Research Institute, Daniel Parmer is an associate research scientist and Elizabeth Tighe is a research scientist. Support for this research was provided by the non-partisan Jewish Electorate Institute.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences, Research