Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

The Inexorable Sense of Life’s Possibilities

A forward-thinking Black Indian Brandeisian excavates his past and comes full circle, back to the Rose Art Museum.

Photo Credit: Mike Lovett

James “Ari” Montford ’74 is a man of many identities. He is a Black Indian, an interdisciplinary artist, a cultural practitioner, a maker, a teacher, a lifelong learner and a cyborg. He is also reevaluating.

After 45 years of educating, curating and creating in more than two dozen arts and academic institutions, exhibiting his work in over 100 shows, earning more than 30 awards and three degrees, Montford is reexamining what it means to have a sense of agency and identity in a tumultuous world. His big thinking, bold intellect and sensitive heart are reflected in his work.

He has described his art—which ranges from painting and collage to installation and performance, all reflecting his dual heritage and its traumatic histories—as an exploration of transculturalism, the essence of relational aesthetics and a way to learn what it means to be “Black Indian.” Through his work, Montford, whose father was Black and whose mother was a member of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, examines false socio-cultural constructs such as racism and stereotyped images. He seeks to deconstruct and better understand the scourge of oppression and subjugation of all Holocausts—including the Jewish Holocaust, the Pan-African Holocaust and the Native American Holocaust—around the globe. Each piece is expansive yet personal, wrestling with the human condition from both macro and micro perspectives.

This duality was manifest during an in-depth Zoom conversation I recently had with Montford – one of the most open, candid discussions with an artist that this longtime art writer has ever experienced. He sits in his studio, surrounded by various materials that suggest an ever-active, perpetually creative mind.

It turns out that I’ve caught Montford at what is a raw, revelatory moment. He is at a point of earnest reflection, having just gone through one of life’s most common yet often existentially impactful experiences: the loss of a parent. Specifically, he is wondering how he made it through nearly five decades as an artist—that is, an extraordinarily hard-working, highly acclaimed and wildly accomplished artist—yet only just recently discovered that his father, who passed away in November 2021 at age 90, had secretly always wanted to be an artist, too.

“When I was going through his personal effects, I came upon a box in his closet,” Montford shares. “At 16 years old, he had taken a correspondence course in art, and he’d kept all his books from it. I also found a letter from his superior officer—he was one of the first group of people in integrated services—giving him permission to use his GI bill to study art. He’d wanted to do it all his life. And back then, it would have been his way of getting out of the segregated south. He’d been carrying around this box his whole life, and nobody knew about it.”

When I suggest that the box sounds like a time capsule, Montford concurs. “Yes, I would agree with that entirely,” he says, adding that he hadn’t yet been able to go through everything, as it is too overwhelming. Named after his father, who did not encourage Montord in his creative pursuits, he is only now realizing that he has lived out his dad’s dream. At the beginning, however, Montford’s path toward art was not intentional.

His life as an artist began at Brandeis, after first coming to campus for decidedly different reasons. “I hadn’t applied—I knew nothing about higher ed at all—but my father said ‘You’re going to be 18, time to get out of the house.’ I was a fairly decent track runner and, at my last track meet, Brandeis coach Norm Levine was there and saw me run. He came up to me after and said, ‘You know, I don’t think I want you on my team, but Brandeis is starting this program called Upward Bound. If you give me your name and address, I’ll pass it to them.’”

He came to Brandeis that summer for Upward Bound, which helps motivate and prepare low-income high school students to explore their potential to become first-generation college students. Recalling that portentous summer with both wonder and defiance in his voice, Montford attests, “They didn't let me go”—he stayed on campus for four years. The rest, however, is not the history one might expect.

Rigor, redirection and the Rose

Montford was admitted into Brandeis but due to the scholarly rigor, he found himself on academic probation by the end of his first year. “My initial experience was one of abject failure, academically,” he says. “It was like going to Mars, and I thought that if I never went back to finish, I could at least say I’d gone to college.”

He did return for his sophomore year and, after being asked to declare a major, he chose art since it was closest to the design and architecture classes that had piqued his interest. By his junior year, he had also decided to minor in education to help make art more saleable. As a senior, he was invited to be in the honors program, which meant 24-hour access to a studio. His world as a creative person was expanding, and, eventually, this trajectory was propelled yet further when he was encouraged to apply to graduate school.

In terms of how this unexpected direction impacted his sense of identity, Montford is characteristically candid and humble. “I was unsure I could be an artist,” he says. “I had no grounding for it at all. It didn’t make sense that you could have a career in that.”

Montford is the first Black Native American graduate of the studio art program at Brandeis, and this notion still seems to spark a sense of amazement in him. “It’s a place where people think you must be smart if you’re there,” he says. “I’m the eldest of four, the first-generation college student in my family and the only one of us to earn a degree. At that time, Brandeis was trying to find ways to be more inclusive and it was a good and bad thing being the only person of color in the art program. I was there, several years after the Department of African and African American Studies was established and there was still just a handful of African American students on campus.”

While at Brandeis, Montford’s learning expanded far beyond art. “I took a course on the Harlem Renaissance in the English department,” he recalls, “and it was a wake-up call, big time. The instructor, Arlene Clift, saved my life. She recognized me as someone who could benefit from what she could offer. I was in awe of her, and she made the difference between me failing and succeeding at Brandeis. She taught me how to write about my culture and allowed me to bring any of my writing to her.

“I had no idea the Harlem Renaissance existed—all I’d known about Harlem was not to go there. Certainly, by the time I finished at Brandeis, I knew about all the reasons I had to go to Harlem, like the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.”

At the end of his senior year, as part of the honors art program, Montford’s work was exhibited in a group show at the Rose Art Museum. “It was fabulous,” he says. “Since it was right around graduation time, I was already overwhelmed but I recall going to the Rose and looking at the work, and it was a gratifying, intense feeling.”

After earning his BA with honors in fine art from Brandeis, Montford went on to earn his masters in art and education at Columbia and an MFA at the Hoffberger School of Painting, which is part of the Maryland Institute College of Art. At Hoffberger, he studied with painter Grace Hartigan, whose vibrant, large-scale abstractions had distinguished her within the New York School of the 1950s and 60s. Her invigorating teaching style greatly impacted his sense of purpose as an artist. “She provided a supportive atelier environment where her students could work and think and explore,” he says. “She believed that creative possibilities are connected to understanding one’s history.”

Over the years, he also studied at Harvard, Yale, the Whitney Museum and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. In addition, he worked with Paolo Soleri, an Italian-born architect who built Arcosanti, a visionary, experimental town in the high desert of Arizona. This immersive experience inspired Montford to consider the concept of futurism, as well as new ways to propel his creative growth forward.

The following two decades took him to cities and educational institutions up and down the East Coast and immersed him in the arts at every level. From exhibiting at Columbia University in New York City, teaching art at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts and coordinating a public art symposium in Connecticut to completing several mural commissions and visiting artist courses in Maryland and lecturing on art history at the Rhode Island School of Design, Montford was in constant motion—geographically, intellectually, professionally and creatively.

Pain, courage and a pivotal moment

In the early 1990s, he began conversations with the leadership then in place at the Rose Art Museum regarding his idea for an exhibit of African American art. The project gelled and, in 1992, he was asked to help coordinate the exhibit in partnership with the museum team. During the process of helping organize the show, Montford realized he wished to submit one of his own works for consideration by the curatorial panel. Much to his disappointment, his piece—an installation—was not accepted, largely due to concern about what was described as its “confrontational aspect.”

Most importantly for Montford, that painful moment in his career heralded a seismic creative shift, one that reverberates still. “By then, I was accomplished enough to be part of this group that was helping the museum put this show together but my own work was rejected, so I decided to stop making art for a time. I was a single parent and depressed and needed to regroup.”

After about a year, Montford found his power once again—and then some. “I applied for a major grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation (named for power-art-couple Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner) and got it,” he says. That, as well as a National Endowment for the Arts grant, helped fund and fuel a newfound creative energy. By then, he had childcare in place so he could focus on artmaking and he became a painting teacher at the Columbia graduate school.

And what happened to his relationship with Brandeis? To be sure, it was a distant one for many years, and his return to the Brandeis art community took time. Ultimately, Montford’s process of reconsideration and reconnection was ignited by a deep intellectual, socio-political and creative kismet that emerged at a campus event centered on honoring the diverse histories and cultures of the BIPOC community.

It began in the fall of 2015, when Montford attended an artist talk organized by Gannit Ankori, a professor of art history and theory, that was part of a series she had put together titled “Art|Race|Activism.” The series was funded by the Brandeis Arts Council and was sponsored by the Departments of Fine Arts and African and African American Studies in partnership with the Rose Art Museum. When Gannit entered the classroom, where the lecture was taking place, she saw a man who had arrived early and introduced herself. It was Montford, and the conversation that began that night continues to this day.

When the event concluded, Gannit asked Montford if he would like to meet some of the students who were occupying the Bernstein-Marcus Administration Center. These student activists, part of the national movement calling for racial justice, named their protest “Ford Hall 2015” and were demanding that administrators work to make the campus more diverse, equitable and inclusive. After introducing Montford to the student protesters, Ankori stayed in touch with Montford, inviting him to have lunch with faculty and students and to be a guest speaker, both in her class and as part of the Art|Race|Activism series.

Ankori was struck by the symbiotic connection between Montford’s art, his core identity and his eloquence. “Ari’s experiences as a Black-Native American artist were reflected in his provocative and bold artworks,” she shared recently via email. “I went to see his work at the Yezerski Gallery in Boston, where he’s represented, and felt his was an extremely important voice that was rarely given prominence in the U.S. I wanted my students to hear him speak about his art and his life.”

Over the years, Ankori kept in touch with Montford, inviting him to events at the Rose and on campus, re-introducing him to the community and following the trajectory of his art.

In 2020, Ankori was named the Henry and Lois Foster Director and Chief Curator of the Rose Art Museum, and she anchored her vision for the museum in a commitment to make it an inclusive and dynamic nexus for art, communities and justice. At the time of her appointment, Ankori said, “We are transforming the Rose into an antiracist, anticolonial institution. We are exploring new inclusive and more equitable ways of being a cutting-edge and inspiring museum that harnesses the power of art and ideas to create social change.”

Generosity, community and an eye on the future

This new chapter for the museum is transformative, and Montford has been part of the transformation. “We are thrilled to be exhibiting Ari’s work as part of our collections exhibition, and to show it alongside renowned artists who have inspired him in his evolution, like Robert Colescott and Grace Hartigan,” Ankori said in a recent Zoom conversation. “Beyond that, we are excited that he is an integral part of the Rose family. He participates in our events and virtual programs and is a valued member of our community.”

Ankori hasn’t been Montford’s only champion in this remarkable story. As his classmates began learning that he was in conversation with the Rose, they decided they wanted to help ensure that his work (selected by the museum’s curatorial team) would become a permanent part of the Rose Art Museum’s collection, which contains more than 9,000 objects, including works by Betye Saar, Andy Warhol, Robert Colescott, Yayoi Kusama, Wilem de Kooning, Yoko Ono, Marisol, and Roy Lichtenstein.

Montford’s classmates had three motivations: They not only wished to support their fellow Brandeisian, they also wanted to help honor the Rose Art Museum’s 60th anniversary, which took place in 2021 and is still being celebrated, and to support the museum’s focus on acquiring more works by BIPOC; women; and gender non-conforming, international and underrepresented artists.

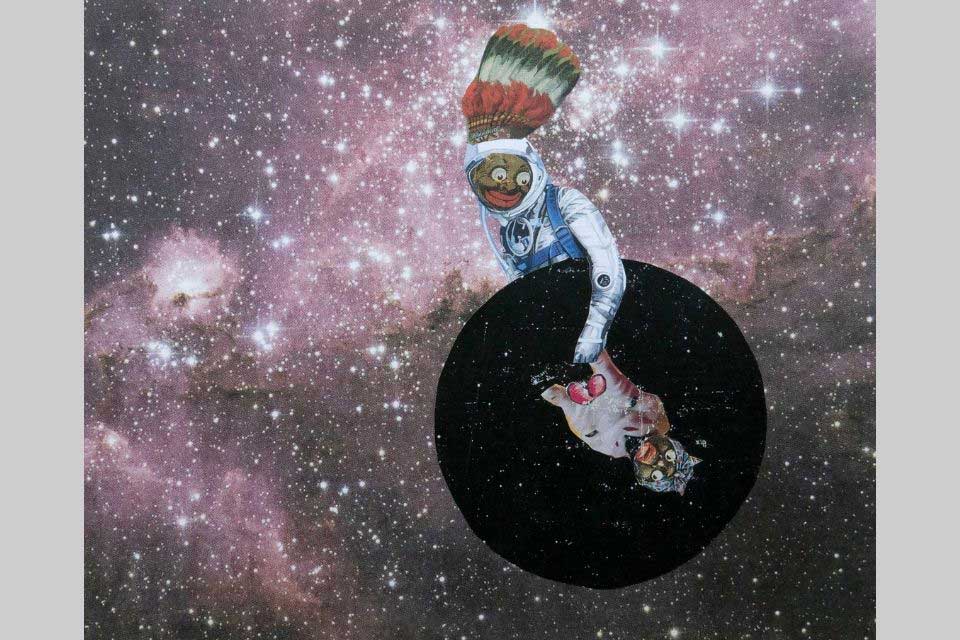

A total of 16 alumni from the Classes of 1973 and 1974 came together to support the purchase of two of the four Montford pieces that are now in the Rose’s collection: “Black Indian in Space: The Goddess,” from 2016, and “The Annunciation,” from 2015, both mixed media collage with oil crayon and paper. Two other Montford collages were gifted to the Rose as well, one by the Yezerski Gallery and the other by a private donor, the latter in honor of the “Ford Hall 2015” student-activists.

The class donation effort was led by Rebecca Pepkowitz-Gilstrop ’73, Dan Klein ’73 and Rose board member Betsy Pfau ’74, and Montford is profoundly moved by the gesture. “I’m really blessed by this gift and that it was spearheaded by a group of people who meant so much to me when we were on campus. This whole experience over the last couple of years…it’s brought a level of community I didn’t experience for 30 years. Looking back on where we were then, I can hardly believe that what has happened is real.”

For Ankori and everyone at the Rose Art Museum, the acquisition of Montford’s work is doubly meaningful. The collages not only embody the foundational social justice mission of the museum, they are also part of a total of 86 works that were donated to the Rose in honor of its 60th anniversary. Ankori, her team and the museum board are immensely grateful to have these important Montford works deepening the collection, as well as advancing its commitment to offer educational programming on diverse histories and cultures.

In all four works donated to the Rose, Montford expresses his expansive, inclusive vision for humanity, a desire for dialogue, questions about the future and a remarkable inner mettle. “The Black Indian in space pieces address the issue of identity,” Montford explains, “and my search for a place I could go to that was separate and apart from the experience here.”

Part of Montford’s interest in space comes from having a pacemaker that relies on satellites to function. A self-described cyborg, Montford says, “In my work, I am addressing the idea of black futurism, living in this black body, still alive because I’m connected to satellites and asking what it would be like to be in space. Will earth become a service world for future Mars inhabitation and will Black people be included in that?”

The iconography and collage media Montford used in the space series come from events, imagery and emotional landscapes he has experienced at various points throughout his life. In the 1980s, he attended a klan rally with fellow artist Barkley Hendricks, and was struck by the truth that racism is endemic and that PTSD, which he defines as Post-Traumatic Slavery Disorder, is ever-present for all African Americans.

“After that klan rally,” he says, “my work became more introspective, with the notion of putting things on black canvases. At that time, I also had a mammy doll and got books that dealt with these caricatures and they started finding their way into the work.”

His inclusion of the stereotypical Native American headdress also comes from inherited ancestral trauma. “Black Indian identity is important to me, and my children also express themselves as Indigenous. Our lineage bloodline is Mashantucket Pequot but our specific clan—the Simonds clan—is not officially recognized by tribal sovereignty. My eldest son Daniel is negotiating with the tribe to bring us in—to bring us home.

“The Indian headdress speaks to me and my experience,” he continues. “I’m living and breathing the stress of being a Black Indian. This is all part of my exploration of transculturalism in the diaspora. The work is the essence of relational aesthetics—it is a relational conversation.”

Montford, whose work is on view in “re: collections, Six Decades at the Rose Art Museum” through 2024, brings our conversation to a thoughtful close. “I’m an artist who is dealing with his issues in his life now out of a process that was laid out for me, to some degree, by my father and his sense of wanting to achieve but being unable to. He was discouraged by the culture of the time. He didn’t achieve it.”

He concludes with a wistful tone yet a glint of determination in his bright eyes. “So, I’m processing all of this…and going for my third Pollock-Krasner grant.”

By making a gift to the Rose Art Museum, you'll join a group of people like you who value our engaging, dynamic – and free – approach to the visual arts. Become a part of the Rose today, and help sustain the full range of our exhibitions, educational programming, operations, and acquisitions. Join today.

About the Author

Annie is senior development writer in advancement communications. Before joining Brandeis in January 2022, she was a writer at Dartmouth College. As a longtime freelance journalist and radio commentator, she has covered art, culture, travel, and education for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, Art in America, Art New England, NPR, and many other outlets. She is the lucky mom of two great kids.