Resistance and Survival Under Nazi Rule

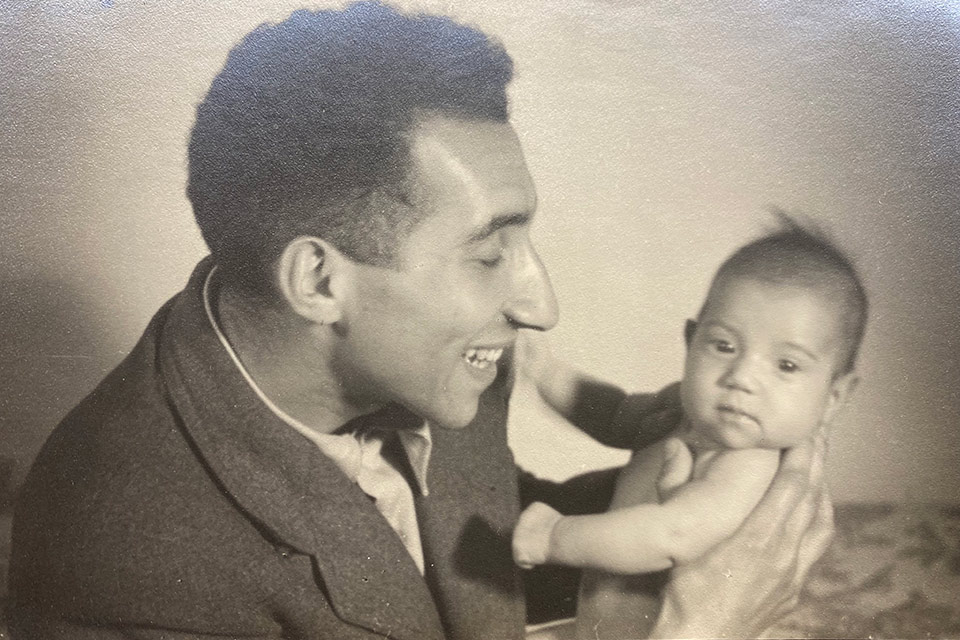

Photo: Courtesy Shulamit Reinharz

Shulamit Reinharz

Last January, the Jewish Book Council named Shulamit Reinharz, GSAS MA’69, PhD’77, the Jacob Potofsky Professor of Sociology, Emerita, one of two finalists for the National Jewish Book Award in the Holocaust Memoir category. Her book “Hiding in Holland: A Resistance Memoir” (Amsterdam Publishers, 2024) tells a Holocaust survivor story in two voices: that of Reinharz’s father, Max M. Rothschild, and Reinharz’s own.

Born in the small, intensely antisemitic town of Gunzenhausen, Germany, in 1921, Rothschild became an avid Zionist as a teenager in Munich. On Kristallnacht, in November 1938, he was deported to Buchenwald, one of the largest Nazi concentration camps in Germany, where he was held for a month before a Zionist organization brokered his release. Soon thereafter, he and Reinharz’s mother, Ilse Strauss, also a German Jew, obtained temporary visas to go to the Netherlands, where they worked as farmhands.

After Germany invaded Holland in May 1940, Rothschild went into hiding in the farming town of Almelo, then moved to Rotterdam, risking his life to be with Ilse. Reinharz was born in Amsterdam in 1946, the year after Holland was liberated from Nazi rule. In 1947, she came to America with her parents.

At age 21, Reinharz discovered a treasure trove of documents in her parents’ suburban New Jersey basement, documents that detailed their lives before their arrival in America. Focused on earning a PhD, initiating an academic career and starting a family, Reinharz transferred the documents into binders she carefully labeled and stored them at her home — without reading their contents.

Forty-five years later — with her elderly parents’ permission — she returned to the binders with the goal of writing a book that integrated the documents, her own experiences with her father and historical research. “It was my good fortune that Dad had written his memoirs in 1980,” Reinharz says. “When I retired from teaching at Brandeis in 2017, I did what I had planned — I sat down with history books, his memoirs and the precious documents to begin to write.” She also spent a summer in Holland, and visited archives and places her father wrote about.

Reinharz says she had several motivations in writing “Hiding in Holland,” including “urging us to remember and learn about the 3.5 million Jews who had survived, just as we remember the 6 million who were murdered.” Exposing the shameful behavior of the Dutch, many of whom collaborated with the Nazis, was another objective, as was exploring the meaning of “resistance.”

Here are three short excerpts from “Hiding in Holland.” The italicized sections represent Reinharz’s father’s voice; the sections in roman type, Reinharz’s voice.

What did imprisonment in Buchenwald teach me? First, to expect violence from Nazis that could easily lead to death. To always expect sadism. That I should stay away from the Germans at any cost and get out of the country as soon as possible. To expect help from relatives working behind the scenes. To expect some generosity but also theft from fellow inmates. But finally, to recognize that I was on my own. I had to make decisions by myself. All of these “Buchenwald lessons” contributed to my survival in the Netherlands.

Dad did not describe everything that occurred in Buchenwald. Instead, he focused on topics he cared about: the humiliation of the Jewish prisoners, the stupidity of the Nazis, the irony of their actions, the disorganization of the camp and the beauty of friendship under these harsh conditions. For example, he described in exquisite detail studying the Bible with a friend on the top slabs of their filthy sleeping structure.

All my life, I struggled with the question of why my friends died while I survived. I struggled with many unanswerable questions concerning my hiding experience, but the only guilt I experienced stemmed from two events in Buchenwald: When I held on to my sweater [an old, sick man was trying to steal it from me while I slept], and when I stood idly by [as ordered] while a fellow Jewish inmate was whipped mercilessly.

There is a difference between asking these questions and suffering from survivor guilt, which, according to psychologists, afflicts people who believe they have done something wrong by surviving a tragic event that others did not survive. Although Dad didn’t suffer survivor guilt, he probably suffered something that could be called “survivor anger” or even “survivor rage.”

I was angry that while I had to hide, my Dutch non-Jewish neighbors went about their business as usual, many of them carrying out the Germans’ murderous plans, such as transporting 75% of Dutch Jews to the Westerbork [concentration] camp in central Holland.

Writing “Hiding in Holland” corrected my view of the Dutch people, a people of enormous contradictions. On the one hand, the Netherlands was the country with the second-highest number of individuals who saved Jews — 5,778. On the other hand, the Netherlands was the Western country with the greatest percentage of Jews murdered during the Holocaust — 75%-85%. Neighboring Belgium’s rate was 45%, and France’s was 25%. My parents hid for three years, protected by a long list of Righteous Gentiles, and pursued by countless Dutch and Germans Nazis.

I am now writing a book about my mother, who, I’m learning, experienced the same events differently.