The Sonic Soul of Notre-Dame

After fire ravaged France’s beloved cathedral in 2019, acoustician Brian F.G. Katz ’90 helped preserve the building’s singular sound — and, in the process, revealed secrets from its past.

By David Levin

Brian F.G. Katz ’90

Photo Credit: Dennis Carlberg

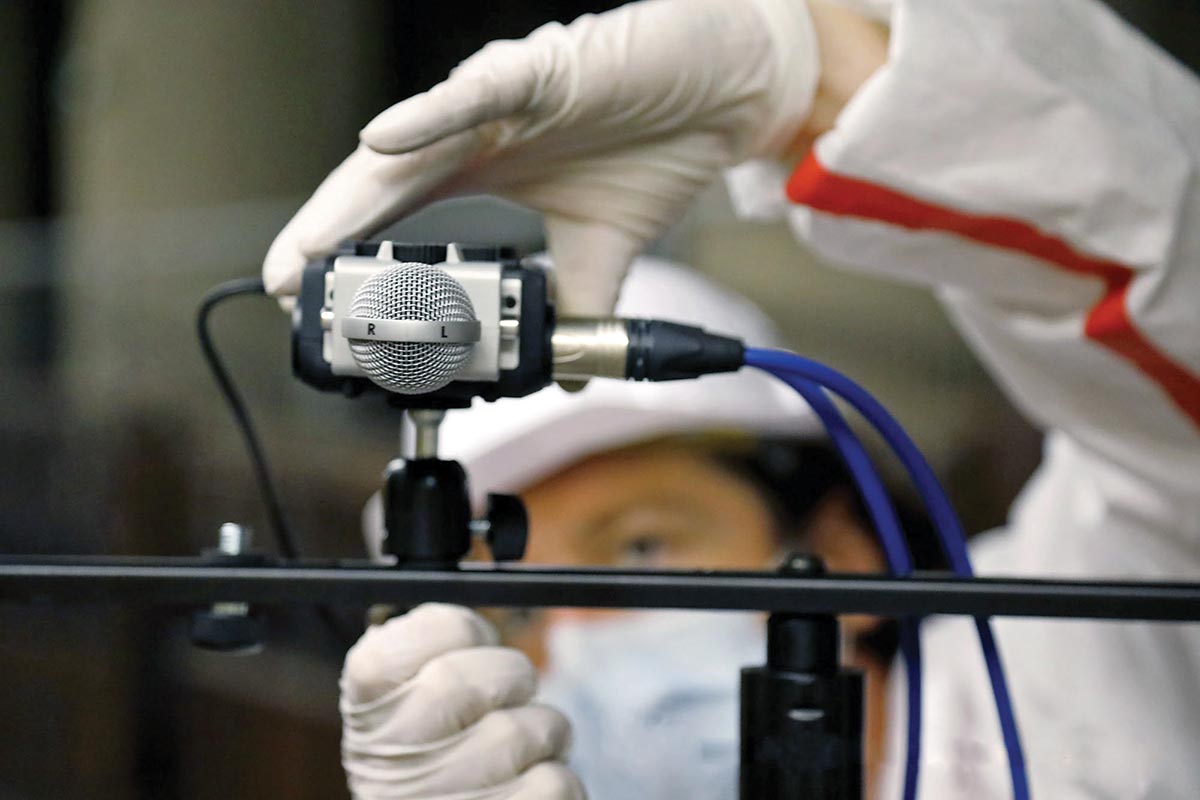

WATCH: Follow along as Katz and his team of researchers record acoustic data after the fire. Explore more videos.

At first, Brian F.G. Katz ’90 didn’t believe his eyes. Flames were towering above Paris’ centuries-old Notre-Dame Cathedral, tearing massive holes in its wood-and-lead roof. As the inferno raged against the evening sky, Parisians stood looking on in disbelief and shock, bringing the surrounding streets to a grinding halt.

Notre-Dame’s catastrophic fire threatened to erase a holy structure, an architectural marvel, a French national symbol. It also threatened the loss of something far more ephemeral: the sound of the building itself. Throughout its long history, voices inside the cathedral’s sanctuary had carried upward, echoing off walls, muddling into one another and forming a long reverberant hum that decayed into the ether.

Katz, an acoustician and research director at Sorbonne University, in Paris — where he has lived for decades — knew the reverberations of Notre-Dame intimately. “You would subconsciously notice its acoustics and immediately react to them,” he says. “You’d hear other people very well, so you’d automatically speak more softly.”

In the wake of the April 2019 fire, he feared visitors might never have that experience again.

Yet in a stroke of incredible luck, Katz found himself in a unique position to preserve the sound of Notre-Dame. In 2015, his research group had collected vast acoustic data from the cathedral, which it had used to create a detailed 3D computer model of the structure. Of all the acoustic labs in France, his alone possessed this information.

The computer model offered a valuable baseline, a measuring stick to ensure builders replicated not just the look of the pre-fire cathedral, but its unique sound as well.

An aural time machine

In the weeks following the fire, absurd and abstract proposals for rebuilding the cathedral flooded the internet. Some called for a sprawling green roof, overflowing with plants. Others, a modern spire and ceiling made entirely of glass. Each audacious recommendation, Katz feared, could obliterate Notre-Dame’s priceless sonic legacy.

To Katz’s relief, French president Emmanuel Macron soon declared the cathedral should be restored to its 2019 state as closely as possible, using identical materials and design. The decision ensured the rebuilt cathedral would have roughly the same acoustics it had before the blaze.

Katz realized his 2015 acoustic data had taken on a newfound importance. His computer model would allow the acoustics of the reconstructed building to be compared to the acoustics of the pre-fire cathedral. It could also shed light on Notre-Dame’s sonic past. Using their modeling techniques, Katz’s team could digitally re-create the cathedral as it was built and altered during the Middle Ages, giving them a way to understand how medieval visitors had experienced the building.

Their model could function, in essence, as a kind of aural time machine.

“We got really excited about how the sound of the building evolved,” Katz says. “Notre-Dame has been in a constant state of change for centuries, whether you’re talking about the architecture, the decorations or just the ways people of different eras have used it.” Within weeks, Katz began assembling a team of musicologists, art historians, architects and acousticians to gather information about the cathedral’s acoustic history.

After medieval workers laid Notre-Dame’s first foundation stones in 1163, construction teams spent another 200 years completing their work. During this time, the partially finished structure remained in constant use. With each new construction phase, the interior sound changed as well. Did those acoustic changes have any impact on medieval culture?

Katz and his team had a hunch they did. The completion of the cathedral’s interior, which approached its final form in the early 13th century, coincided with a massive development in Western musical style. A group of in-house musicians called the Notre-Dame School began to move away from Gregorian chant, a technique in which every performer sings the same notes in unison. For the first time, these musicians embraced a style called polyphony, singing different musical phrases that played off one another to form rapidly changing harmonies and rhythms.

This new style proved wildly popular. According to a contemporary account from the Bishop of Chartres, “When one hears the excessively caressing melodies of voices beginning, chiming in, carrying the air, dying away, rising again and dominating, he may well believe that it is the song of the sirens and not the sound of men’s voices.” (This was both a blessing and a curse, the bishop added: When taken in excess, polyphony was “more likely to stir lascivious sensations in the loin than devotion in the heart.”)

Solving a medieval mystery

Katz’s research offers compelling evidence that the architecture of Notre-Dame helped give birth to polyphony.

Before huge cathedrals like Notre-Dame came along, most large churches were constructed in the style of Roman basilicas — long, broad buildings with dense stone walls and relatively low ceilings. Any sound made within these interiors would have bounced around for a long time, making speech and music difficult to understand. That’s why, within these spaces, choirs favored the slow plod of Gregorian chant.

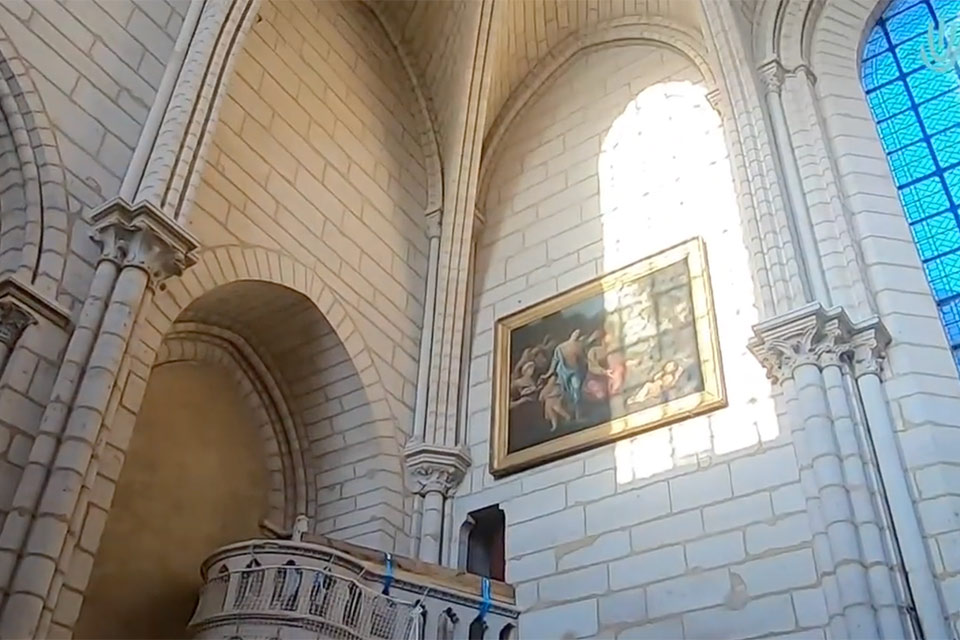

Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame, however, turned that broad, flat space on its head, creating a volume that’s narrow and tall. With interior walls situated closer to one another, acoustic reflections in the church’s choir and apse — the semicircular area at the head of the cathedral, where clergy sit — bounced back quickly, making the music sound clearer to performers. Perhaps more important, it also sounded clearer to the highranking church officials seated nearby.

In the area where the cathedral’s medieval choir would have sung, Katz’s team found low frequencies reverberated for six to eight seconds before dying out. Higher frequencies, like a tenor or a soprano voice, echoed for only about three seconds. Medieval singers would have been forced to change notes slowly when singing in bass registers to remain intelligible; singers in higher registers, however, could move nimbly and still be understood.

This pattern closely matches the style of the medieval organum, a type of early polyphonic choral music performed at Notre-Dame in the early 1200s.

Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame turned the broad, flat space of earlier churches on its head. In a narrow and tall interior, acoustic reflections in the choir and apse bounce back quickly.

Sorbonne graduate student Sarabeth Mullins used Katz’s acoustic data to create four different computer models of Notre-Dame. Three of them replicated each stage of the cathedral’s initial construction. Another re-created a basilica that once stood on the cathedral’s site.

In a recording studio specially constructed to eliminate echoes, Mullins asked a group of medieval music specialists to sing 12th-century organum into a set of microphones, then fed this signal through her virtual models and back into the singers’ headphones in real time. The performers could hear what it was like to sing the music in each space and react accordingly.

“With the click of a button, we could say, ‘Now you’re in the 13th century,’ ‘Now you’re in the 12th century,’ and have them sing the same song in four different periods,” she explains.

When changing the sound model between the different eras, Mullins took note of the singers’ body language, expressions and musical coordination. As the acoustics went further back in time, the singers seemed noticeably uncomfortable, drifting out of sync with one another and becoming increasingly disoriented. As soon as Mullins switched to the model matching the era of the Notre-Dame School, however, the group of performers seemed to gel immediately.

This, she says, hints that medieval musicians and composers likely noticed Notre-Dame’s acoustic effects and incorporated them into their work. The idea makes sense: It would have behooved composers to tailor their music to this particular venue. During the medieval era, Notre-Dame held close ties to the French monarchy and the Catholic Church, making it a nexus of political and religious power.

“Its political position carried a lot of weight,” Katz says. “If you got your music played there and it sounded great, you could probably get it performed in other churches. It was a stamp of approval. That’s why Notre-Dame was more important than a comparable cathedral with the same acoustics.”

In other words, says musicology doctoral candidate Valérie Le Page, who collaborated on the project, “medieval musicians were simply trying something new — and they found the right place to sing it.”

Echoes of cultural heritage

The sonic investigations Katz and his team engage in fall into the niche field of archaeoacoustics — the study of historic soundscapes and their impact on past cultures. By analyzing something as ephemeral as sound in a centuries-old place, Katz gains insight into the architecture of the past and the art it may have inspired.

Notre-Dame isn’t the only place he and his colleagues have attempted such a project. In 2013, he led a similar modeling effort at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, a small Romanesque chapel across the Seine from Notre-Dame, which predates the cathedral by 150 years. He has also resurrected the soundscape of former Paris landmarks like the Palais du Trocadéro, a massive 19th-century performance hall.

Rendering the sounds of centuries-old spaces provides a unique new way to understand cultural heritage, Katz says. The work has a natural allure. For fellow researchers, it provides a window into history that would otherwise be impossible to obtain. For everyone else, it’s an irresistible, emotional way to access our shared past.

With the latter goal in mind, Katz has collaborated with a team of historians and artists to create immersive walking tours of Notre-Dame. Together, they’ve re-created the soundscapes of the neighborhoods around the cathedral during a variety of historical eras. They’ve also made it possible to hear medieval music as it was originally experienced inside the cathedral, making history come alive for audiences worldwide.

Today, Notre-Dame, which reopened to the public last December, sounds more or less like the pre-fire building did. Katz’s team has already measured the restored cathedral’s acoustics to document any changes that have taken place, though it may take up to a year to analyze the hours of audio data collected.

Today’s Notre-Dame, which reopened in December, sounds much like the pre-fire building. Katz’s team is documenting the subtle changes.

Clean limestone walls reflect sound more readily than dusty ones, so the new building is likely more reverberant, Katz says, though most ears won’t hear the difference. Such subtle changes are, in their own way, a living part of the structure’s history.

“There is a tendency among modern visitors to conceptualize a cathedral as a still and constant witness to history,” Katz and Mullins wrote in a 2023 paper. Yet over centuries, every generation leaves its marks on a cathedral in one way or another.

Whether you tweak the architecture, revise floor plans or complete a renovation, Katz says, “to modify Notre-Dame is to participate in a cultural legacy of continuous change.”