Henry Grossman '58: Behind the lens with the Beatles

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Fab Four's arrival in the U.S.

Henry Grossman '58 photographed them all. From Eleanor Roosevelt to John F. Kennedy, Marc Chagall to E.E. Cummings, David Ben-Gurion to Henry Kissinger.

And that was just as a theater arts student at Brandeis.

By the time Grossman graduated, he had a portfolio good enough to land him an assignment that would be the envy of music fans the world over: Shooting the Beatles’ first performance in America.

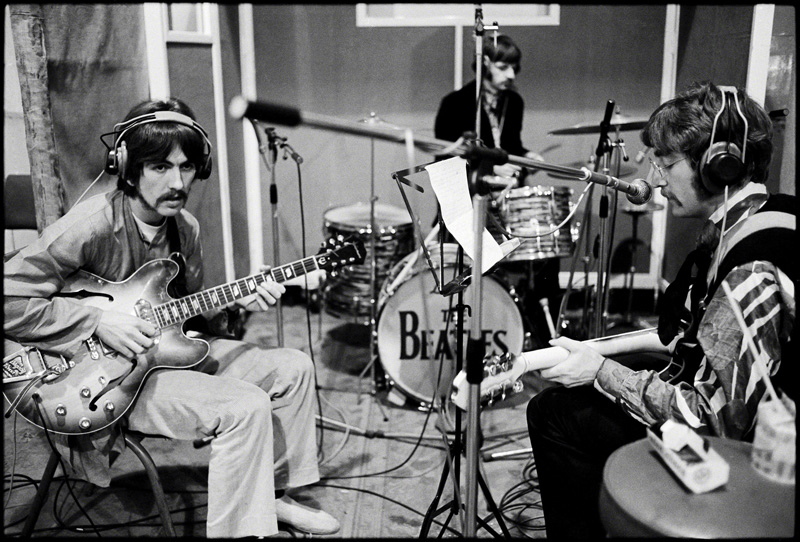

Grossman went on to take more than 6,000 photographs of the Beatles between 1964 and 1968, including on locations for the film “Help!” In late 2012, Curvebender Publishing released the limited-edition “Places I Remember,” a 526-page coffee-table book composed of Grossman’s photos. Some of his photos will also appear in New York’s Gallery 151’s exhibit celebrating the enduring impact of Beatles’ appearance on the “Ed Sullivan Show” half a century ago.

Grossman recently spoke with BrandeisNow about his experience working the Beatles and seeing them from behind the lens as well being with them behind the scenes.

You first met The Beatles 50 years ago on Feb. 9, 1964. What do you recall of that day?

I was at the “Ed Sullivan Show” for Time magazine. I photographed them and the screaming kids, and afterwards they posed for some pictures.

A couple of weeks later the English newspapers saw the pictures in Time magazine, and sent me to Atlantic City to work with them. I had spent the afternoon with them there, playing Monopoly and cards, and at one point I said to Ringo, “How are you enjoying the American tour?” He took me to by the arm, led me to the window, and pointed a block away. There was a brick wall, a building in between the brick wall and a parking lot. He looked at me and said, “This is all we’re seeing of America.” They couldn’t go out.

Were you already familiar with their music?

I didn’t listen to their music. I didn’t care for their music. When I met them and I got to know them, I really liked them.

Did you consider it an exciting assignment at the time?

It was an assignment. I was very happy – always happy to have one.

I was amazed at some of the girls, who had tears on their faces. Incredible. I had never seen that before. And when I went to Atlantic City for the concert, I had a picture of policemen standing next to the stage with his hands covering his ears, not because of the music but because the screaming was so loud. You know, jarring.

I really got to know them better in Austria and the Bahamas. While they didn’t have a college education, they were very sophisticated in terms of having more points of reference. I got to know them the next year when they went to Nassau. At one point George asked me what’s another word for such and such, and I didn’t know what the word was. I said let’s look it up in the Roget’s Thesaurus and he said, “What’s that?” So I went out and bought him one. Sometime later, a year or two later, there was an article where he said “A friend brought me a thesaurus so I can find all the words I need.” My education fed their education, and they fed me.

What was it like to spend time with them?

I’ve been asked, “Was I around when all the girls were throwing themselves at the Beatles? And what about the drugs, did I enjoy some of that?” But I never saw any of that. When I was photographing them, they were at home with their families and wives, or they were working. I never saw, I was not involved in any of that.

At one point I said to Ringo, “I wish I had the guts to wear a tie like that,” and he came over and fingered my tie – it was a paisley tie from Liberty of London – and he just looked me in the eye and said, “Well, you could wear a tie like this and you’d still be Henry, with a bright tie.” That had never occurred to me. They weren’t wearing costumes, those were their clothes.

I remember when I went over to George’s house for the first time. He asked me to come and take some pictures of him and Pattie. There was an instrument on the wall. He was showing me around and I looked at it and said, “What is that?” He reached up and took it down, which meant that it wasn’t just a decoration. He started trying to tune it and he said, “It’s a sitar, but I can’t find anybody to teach me.” I looked at him, and I said, “George, you make a lot of money.” He smiled, and I said, “You could probably afford to find the best sitar teacher in India and bring him over here to work with you.” That year he went to India. I didn’t say go to India… You know, so the education went both ways: realizing what they could do and what world was open to them.

Did the music ever grow on you?

At that time I was a fan of the people, but now I love all the early music, the early songs. I still listen to pop rock and stuff like that. “Strawberry Fields,” “Eleanor Rigby,” that kind of stuff - the melodic stuff.

Did you think their fame and fortune would last?

I was in George’s house once, and we were talking, and he said, “Who knows how much longer this is going to last?” Well, now we see it’s lasted 50 years, and it changed the world of music in a major way.

I was with Bobby Kennedy on an airplane about a month before he was killed. I was assigned by his company to get posters on the tour for the campaign, and I remember sitting three feet away from him and looking at him and thinking, “Oh, my God, this man is going to be president of the United States.” I never thought that kind of thing – “My God, these Beatles are going to be even more famous than they are now.” They were world famous, they couldn’t even go out.

That’s one of the reasons I did not bother John when he was in New York, and we lived only within 10 blocks or five blocks of each other. I didn’t because I knew how much they hated the press always coming at them, and the fans. I’m sorry now that I didn’t.

You photographed them quite a bit between 1964 and 1968. Did you keep in touch after that?

I stayed in touch with George. In 1974, People magazine sent me to photograph him for a cover in San Francisco. He was going to do a world U.S. tour with Ravi Shankar, and by the end of the evening, it was like meeting an old friend again. It was like we were brothers. It was terrific, and he asked me to be the photographer on the tour for six months.

It’s often commented that your pictures of the Beatles back in 1964 were especially interesting because they weren’t all close-ups of the band, but they captured the whole scene, including all the other journalists.

Ben-Gurion came to Brandeis, spent a week at Brandeis, I got to know him and his staff. He came, then went to New York and I rushed to New York to bring some of his pictures that I had shot at Brandeis to Time and Newsweek, etc. His security people knew me and that I was good. Time magazine took one of my portraits, and I brought the pictures to Life magazine, and Life said, “No, Henry, if you want to work for us, you have to take five less good but more storytelling pictures,” and that was the beginning.

How did that influence your future work?

I was a reporter. I wanted to capture the surroundings – what was going on, who was around, where they were, how they did this or whatever. That became rather important – not to stand and pose for a souvenir of the four guys together. I wish now I had more pictures of the guys together. But at that time it didn’t occur to me to pose them. There were others getting those kind of pictures, I was getting the more personal shots.

When you look back at those photos, do you think of the time or of the shot?

I think of the time. I’m glad that you point that out, it’s a very important thing. I’m not thinking of that photo, I’m remembering the event and the time. That’s what it should be. It’s a souvenir of the time. I started taking pictures for myself. Souvenirs. To remember. People that I liked or knew. That kind of stuff. That’s what my photography has been really for me.

For more on Grossman, check out the Brandeis Magazine profile.

Categories: Arts