Bringing spatial disorientation to the stage

By Kennedy Ryan

Photo Credit: Dan Holmes

April 26, 2024

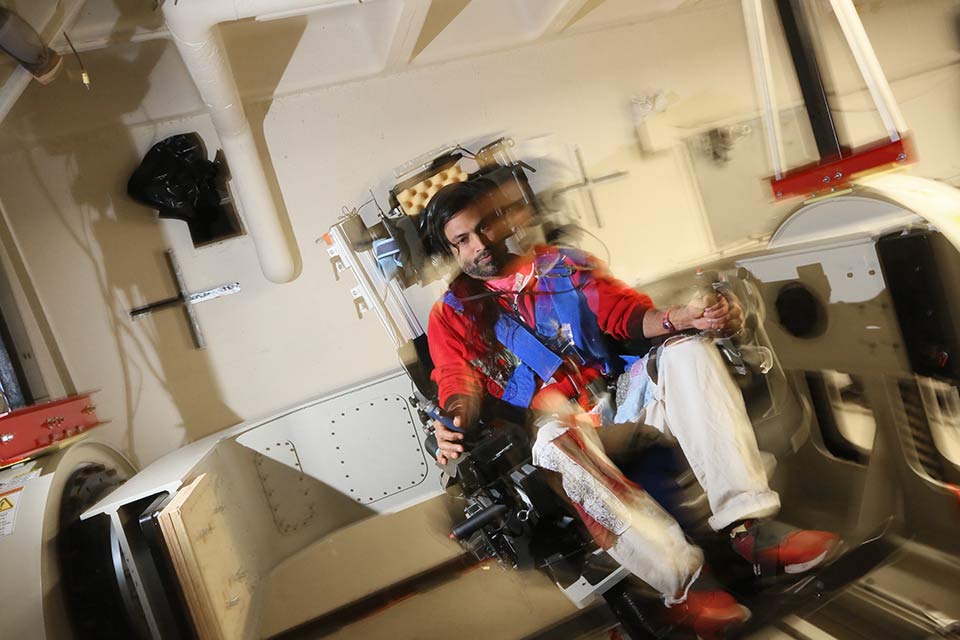

Vivekanand Vimal, GSAS PhD’17, a research scientist in the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Lab, studies the use of vibration cues as a countermeasure for spatial disorientation. In space, astronauts can become disoriented, sometimes causing fatal accidents.

With funding from the NASA Human Research Program, Vimal studies how to build a strong bond between humans and devices in disorienting spaceflight simulations with analog conditions where people cannot rely on their own biological sensors.

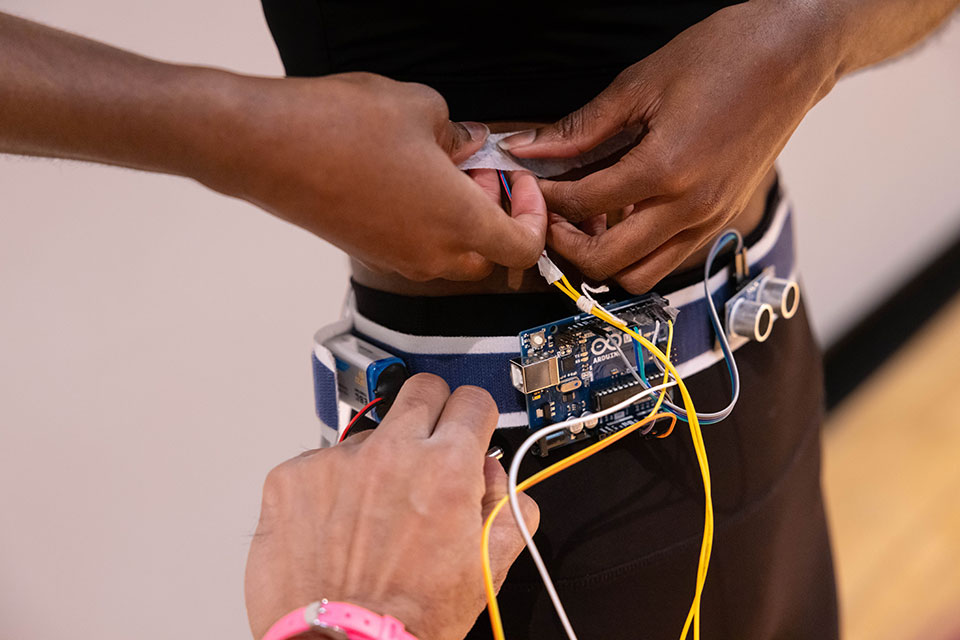

Vimal wanted to explore human augmentation through vibration cues outside of the lab in complex tasks such as dance, to deepen his understanding of the science and to also engage the larger community. To make that happen, he worked alongside a community of mostly non-academics interested in human augmentation called the Technology Research Interdisciplinary Group, which he co-founded with Brandeis undergraduate students. With the help of Marco Qin ’24, they created a homemade sensory augmentation device that converts distance into vibrations.

Vimal decided that dancers would be the ideal participants in this project. Vimal’s goal was to explore how vibrational cues could affect movement during dance, and whether dancers could achieve feelings of immersion and oneness with the device.

He connected with costume designer Brooke Stanton in the Department of Theater Arts, and the two brainstormed to explore how to incorporate this technology with fashion and dance.

“I only had an idea to use these devices to explore dance but no capability to implement it,” Vimal said. “She added lots of symbolism and depth and then everything began snowballing because she pulled together so many people.”

Stanton worked alongside a team of students to create costumes that feature circle skirts constructed from recycled business suits. The skirts, when pulled by attached strings, reveal colorful recycled silk saris underneath, which expand outward like a honeycomb to transform the dancers into planets and stars. The devices, worn around the dancers’ waists, converted the distance between dancers into vibrations. The goal was to see whether they could orbit one another through the routine.

“We found dancers who were majoring in disciplines related to science and math,” said Stanton. “As dancers, they’re so in tune with their bodies they are able to provide helpful feedback. Once they got the hang of it, the movement was very fluid.”

The routine was choreographed by Greg Roitbourd ’26, a physics and theater arts major with over 10 years of experience in ballroom dancing. He drew inspiration from folk dancing, mathematical shapes, circles, and the solar system.

“I’m very excited to see where this leads me,” said Roitbourd. “It’s opening cool doors and is a cool experience in both the arts and sciences.”

Pictures of the dress rehearsal and the concepts of the dance and vibrational cues were shared during the NASA Human Research Program conference in February 2024.

The team performed their showcase during the Leonard Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts.

Vimal is excited about new contributions this project will bring to his research inside of the lab.

“The research that I do with the vibrotactors in the lab is very controlled and very constrained,” he said. “When you put these devices on people who are doing very complex movements with dance, we can ask really deep questions. The dancers have talked about embodiment, like when you become one with the sensor. These are kind of deep ideas that the literature hasn't fully explored or understood.”