On Composing

↑Lazarof was interviewed many times throughout his life about his thoughts on music and his approach to composition. Newsclippings, selections from several radio interviews, as well as a public lecture he gave on the subject, can be found below. The full radio interviews can be heard on the Brandeis Distinctive Collections page.

Newsclippings

Article about Lazarof discussing his composing style

“Composer Discusses Musical Experimentation”

UCLA DAILY BRUIN

February 21,1966

By Stephana Roth

DB Staff Writer

Transcript

“The experimental aspect of music is an organic part of any description of style,” according to Henri Lazarof, assistant professor of music. “One must differentiate between works whose only experimentation occurs during the composition and those which allow experimentation on stage.”

“My works fall into the first group; they are rigidly controlled,” he said, “as far as possible, that is.”

Five of his major works will be performed by nine guest artists in a faculty recital at 8:30 p. m. Wednesday in Schoenberg Aud.

All five works have been composed since 1962 when Lazarof joined the Music Dept. here. His most recent composition, “Entr'acte,” is being performed publicly for the first time.

“Some of the artists who will appear were integrally involved with the works they will play,” Lazarof said. “Inventions for Viola and Piano” was composed expressly for Milton Thomas and Georgia Akst, and violist Maxine Johnson commissioned him to write “Tempi Concerti” which Lazarof will conduct at the recital.

Lazarof was born in Bulgaria. He studied there, in Israel and Italy and came to the United States in 1957 on a scholarship from Brandeis University. He received his MA there and joined the faculty here in 1959 as a member of the French Dept. He speaks eight languages fluently.

The young composer places himself calendar-wise as part of the 20th century, but he is not preoccupied with labels. “Adjectives do not matter much. 'Free' is the most important word,” he explained.

But in the sense that his works are controlled, he admits to being a traditionalist. “Just as long as one composes, that’s all that matters” “I have no mental block, no preconceived ideas, when l sit down to compose,” Lazarof commented. He uses a piano if he needs it, but many works are composed at the desk in his office in Schoenberg Hall.

A former student of Italy’s Goffredo Petrassi, Lazarof is himself happiest when he is teaching good students, no matter what course. He teaches composition, orchestration and counterpoint among others.

“A 'good' student does not necessarily mean a talented one; rather a dedicated one,” he said. “Good musical education should be part of a university. Music is not an isolated aspect of culture. Performance is important, of course, for both student and faculty.” Lazarof has taught since his early teens, and says that he won't give it up.

“It is part of creative work. I believe in it. It is a perpetuation and extension of writing,” he concluded.

Article in which Lazarof discusses contemporary composing

“Contemporary Music: Necessary”

Avant Garde Composer

Rocky Mountain Review April 9

Transcript

Contemporary music is a necessary part of the environment of the 20th Century and whether it’s ‘liked’ or not it is of secondary importance, says composer Henri Lazarof of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mr Lazarof is on the University of Utah campus to hear his composition, “Odes for Orchestra,” performed by the Utah Symphony Orchestra. The orchestra is in residence at the Unlversity under a Rockefeller Foundation grant and is playing compositions of five young American composers. All music is contemporary and has never before been performed by full orchestra.

Mr. Lazarof, a native of Bulgaria, is probably the most avant garde of the five.

Basically, he believes contemporary music is the “natural thing for contemporary composers.”

“We should not use the great masters as a mattress to sleep on,” he says. “The great masters will always exist, but we must write music to reflect our present culture.”

The matter of musical composition is the same today as it was in the time of Bach, Haydn or Beethoven. In those days there was the bad as well as the good, as is the case today, says Mr. Lazarof.

He says if the masters were composing in the 20th century, they would be writing the same kind of music as is being written today.

Contemporary music now sounds, in some cases odd to listeners who are dedicated to the works of the masters. This probably was the case at the time that music was written, he says.

Contemporary music cannot be generalized. Jazz, both here and abroad, has had considerable influence on classical now being composed, but there are other influences. The arts and sciences are making their impact.

The most important thing, says Mr. Lazarof, is that the artists of today face reality.

“We are living in the most exciting time in history,” he says.

“Only the Renaissance can compare with it in impact. It has already resulted in a very important revolution in music. The only way is forward. The way is wide open.”

Mr. Lazarof’s composition is described by himself as “a delicate, transparent work.” It spontaneously gives birth to perpetual changes. It can be performed with a full or chamber orchestra.

“It is pure music--sound verse, and as abstract as it can be,” he says.

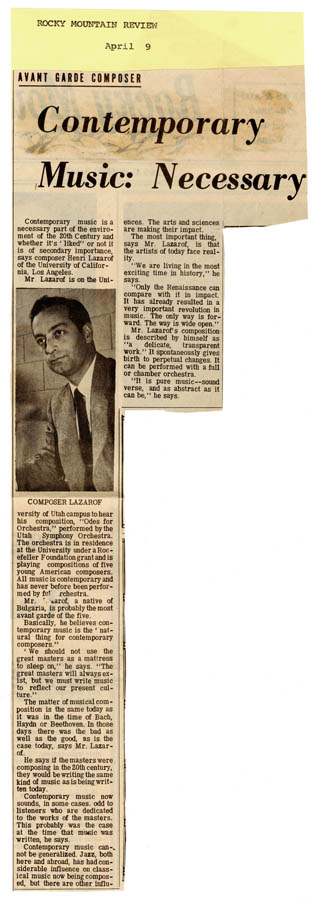

“Sounds from a Composer’s World”

Flyer announcing Lazarof’s lecture “Sounds from a Composer’s World”

Transcript

UCLA Committee on Fine Arts Productions and Public Lectures presents

HENRI LAZAROF

Composer

Appointee, University of California Institute for Creative Arts (1963)

In a Public Lecture

“Sounds from a Composer’s World”

Tuesday, February 25, 1964, 8:00 pm

Economics Building 147

No Admission Charge

You Are Cordially Invited

In Connection with the Third Concert in the Series

Music of the 20th Century

Saturday, February 29, Schoenberg Hall, 8:30 p.m.

Compositions by Outstanding American and European Contemporaries:

Pierre Boulez

Niccolo Castiglioni

Andrew Imbrie (UC, Berkeley)

Richard Swift (UC David)

And by Two Masters of the Older Generation:

BELA BARTOK: Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion

ANTON WEBERN - Quartet with Saxophone, Op 22

General Admission: $2.75

Students: $1.00

Tickets for the Concert on sale at the

UCLA CONCERT TICKET OFFICE,

10851 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles 24,

Monday - Friday, 9:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M.,

Saturdays from 9:00 A.M. to 12:00 Noon.

Phone GRanite 8-7578 for information.

UCLA 50¢ Student Tickets on sale at ASUCLA Ticket Office, Kerchkoff Hall 200.

“Sounds From a Composer’s World”

A Lecture by Henri Lazarof

Full scan of the annotated, typewritten document. PDF

Transcript

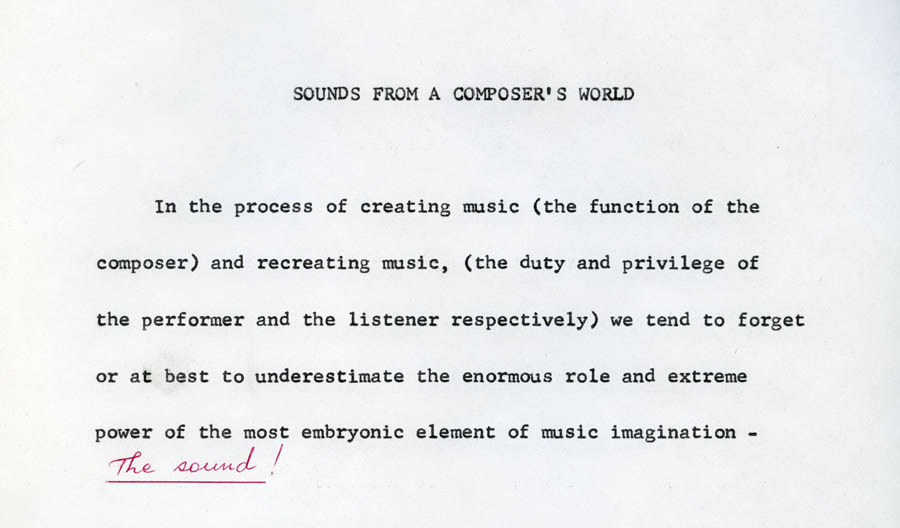

In the process of creating music (the function of the composer) and recreating music, (the duty and privilege of the performer and the listener respectively) we tend to forget or at best to underestimate the enormous role and extreme power of the most embryonic element of music imagination - [ Handwritten by Lazarof: The sound!]

Overwhelming in its total output of sounds, a musical composition tends to dissipate this most basic element and ultimately to destroy it. By destruction I mean pulverizing its individual existence, its independence. Far from condemning or criticizing any of the existing approaches to musical composition I would only like to draw your attention to the enigma of the sound.

I believe that a sound should be conceived as a small universe of itself and by itself, a universe with specific shape, qualities and direction. In the field of physical acoustics, the question that is primarily of interest to the psychology of music is what physical processes must take place in order to produce a sensation of sound. Here I quote a well known scholar in the field:

“Sound production can best be demonstrated with the aid of a catgut string. If we pluck a string that is firmly fixed at both ends, we can see with the naked eye that it is set into rapid vibration. This vibration is then communicated to the sounding board , and through this to the surrounding air particles, which in turn set up vibrations in the tympanic membrane. This motion is propagated in the inner ear to the auditory centre located in the brain, where certain still unknown physiological processes produce the sensation of sound.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Unquote]

As you can see, there is nothing better that a composer would like to avoid than this kind of scientific approach to the world of the sound - cold, mechanically organic, unpoetic, unartistically descriptive. Perhaps a more imaginative, carefully controlled explanation could be substituted.

The life of a sound has a multitude of stages before reaching its final goal - namely its projection to the listener and the listener’s reaction to it. Some of the different stages, the way I see them are:

- The basic conception or primary realization

- The creation itself in its inaudible form = notation

- The reproduction - or the audible form and

- The most important stage = the countra-sound or the reaction of the sound to itself.

The basic conception of a sound (or its primary realization) begins in a moment conditioned by a series of chemical reactions according to a given mental and physical state of a human being.

I have oversimplified my definition by saying that the conception of a sound begins in a certain moment instead of saying that a change of zone occurs in its existence. By change of zone, of plateau or sphere, I mean that the continuous existence of the sound is temporarily interrupted during which time its vital components take shape. Thus, pitch, density and its [ Lazarof crossed out vibration and handwrote in derivation] timbre - begin their important role.

If I may illustrate this with an analogous example: imagine a moving string or a tape with no beginning and no end. If you are to splice this tape in 2 places, and then retape the 2 remaining parts, you will obtain a separate piece of tape while the original one continues its “life.” Thus a unit of sound is being separated from its continuous rotation and begins orbiting around itself. The place of the separation will be guided by our intuition, instinct, inner ear, will, or by our creative imagination.

So far, very little has been needed from us - just awareness of the continuous existence of the sound, awareness of being constantly surrounded by it, the awareness of the sonorous world!

PERHAPS IT WILL BE INTERESTING TO MENTION the fact that there are certain persons who automatically associate sounds and sound qualities with distincts colors. Their identification of isolated sounds is due not to the primary acoustic impression, but to the optical or intuitive image associated with it. The painter Kandinsky claimed that he sensed a similarity between “tone color” and “color tone”. He felt a constant relationship for example, between:

- light blue and the sounds of the flute

- dark " " " " " " cello

- green and the sounds of the violin

- red and the flourish of trumpets

- vermilion and the ruffle of drums

- orange and the church bells

- violet and the horn and bassoon.

For the professional musician, the word timbre has not quite the same connotation, though very often we hear the expression of “beautiful colors” in relation to a certain musical phrase, meaning a specific sound texture of this phrase.

One of the aspects of music that contemporary composers have tried to restore, in many cases successfully, is exactly the timbre, which fortifies even more the independence and the expressive power of the sound as a unit.

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: 1.- Schoenberg - “5 Pieces for Orchestra” ep. 16, 1909,]

2.- Castiglioni - “Tropi”, 1959 4’ 20”

(#3 “Morning by the Lake” - [ unintelligible] 3’ 50”]

A second very important aspect of music and organically related to ‘timbre’ is the question of direction given to sound. What is the meaning of this? → If one is to adopt the approach to sound as a complete unit, a universe by itself, this is to assume that the sound has a life of its own with the necessary movements. Movement implies direction, or, in other words - in music - a distance and a connection between sounds.

To cover this distance the sound has to travel, abandoning its rotation around itself. From here on, the sound acquires a split or dual embodiment: that of actual vibration and the one of visionary resonance or silence. In plain words, this is called rest and its use in music goes back to prehistoric times. Up to modern times, rests have always been used in a passive way - for example, to allow the singers to catch their breath or, with the appearance of polyphonic music, to indicate the temporary cessation of a voice while a second one makes its appearance. To the best of my knowledge, the use of silence in an active way began in recent times. The basic idea behind it is that: in the process of moving, the sound changes altitudes; in reaching a certain plateau, it activates itself, generating a certain amount of tension (commonly known as expression) which is used either to create a second actual sound or a multitude of physically nonexisting ones, but emotionally always present, at least for the concentrated listener, regardless of his musical sophistication.

We are, after all, dealing here with a most intangible element - the artistic phenomenae of the reproduction itself. In this way, silence becomes creative and it poses its demands upon the listener - namely to procreate it. Thus the continuity of the sound, and ultimately of music, is secured!

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Castiglioni -- “Tropi”, 1959 3’32”]

Without doubt, a thesis of this sort will encounter countless objections, among which the most tempestuously prominent will be the one of the delineation between the role of the composer and that of the listener. Have no fear: the demarcation line will establish itself without delay, for the most creative type of listener will never be able to follow the mind of the real creator, but nevertheless this procedure will sharpen his ear and mind with the hope that the gap between him and the a new work of art will be somewhat narrowed.

And so, following the metamorphosis of the word “direction” through movement, distance and connection, we see that it all boils down to a relation: that of a sound to a sound in space. The moment a relation is mentioned, the ground is prepared for the human mind to spread its tendency for generalization and to immediately organize a canon of set rules and regulations. Thus, for centuries the relation between sounds, as components of melodies and harmonies; has been regulated by principles most frequently established by rather mediocre creative people. Very seldom will we find a masterwork which did not break the established rules of its time. So in modern times, too, rules replaced previous rules, principles based on democracy replaced those founded on tonal despotism and perhaps the destiny of all sonorous phenomenae will always have to be limited by restrictions. However, in the past 50 years, extraordinary changes have occured in the musical thinking of contemporary composers which, fortunately, have brought about an enormous liberalization in the matter of sound relation. Distances presumed totally unearthly have been narrowed down to being easily conceived, applied, and sometimes even accepted by the public.

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Weber -- 5 Mvt. for String Quartet (I + III), 1909 3’53”]

Thus we see how color and direction are vitally important to the countra-sound, to the reaction of the sound to itself or, in other words, to the continuous flow of sounds. No doubt music is expression; technically speaking, expression is based upon change, contrast, which pushed to extremes sometimes is bound to produce exhilarating results. Granted, that color has expression per se, but for a limited time - the necessity for change becomes evident very soon - therefore the change to a different color which does not necessarily have to be associated with the previous one. Here we approach more disputable grounds! The question of content emerges out of tradition and with it its product- form! Contemporary music has many times been reproached its lack of content and as a result its lack of form. After the performance of a new work one can very often hear the questions: “Where is the idea?” or- “What is the idea behind it?”

No doubt these questions stem out of the extraordinarily rich tradition of musical culture - from Bach to Mozart, Beethoven Brahms- ( I will stop right here!)

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: What do we call “idea” in traditional music?]

Is it a phrase of a few bars long, a theme, a short motif of a few notes, a simple or more complex chord - or is it what gives in many instances the only clue to the music critic for the understanding - or misunderstanding of a composition?

Can we call the 4 notes based on the name of Bach (B-A-C-H), or the beginning of Beethoven’s 5th Symphonie (4 notes again) can we call them “ideas” or do we need the lengthy “4 notes” of the opening of the Magnificent 4th Symphonie of Brahms in order to determine the meaning of the word “idea”? A very knowledgeable and prominent composer whose work is deeply rooted in tradition has defined “musical idea” as the starting point in the work of a composer. - This is already a more flexible non-definition. - How many times in the past have the “ideas” of a specific work become clearer, if not apparent for the first time, only with the help of the development? Development suggests form, and when form becomes a predominant criteria the result will be inevitably sterile, if not disastrous.

There is a story about Maurice Ravel who, when asked about the progress of his most recent work, replied that he had it all finished except the themes!

Following this process of musical investigation, we should undoubtedly reach the conclusion that any kind of musical material can constitute a musical idea. And, as we have seen previously, the basic unit of music being sound, which by its continuous existence provides an infinity of supply, there is an unlimited possibility of works to be produced, regardless of the gigantic amount of works written in the past. I believe that this kind of optimistically constructive approach is necessary for the young artist tormented by the multiplying pressures and possibilities of modern times and incessantly haunted by the accomplishments of the Masters.

MUSICAL COMPOSITION

Basically, musical composition deals with relations: obtaining the best possible balance between these relations will establish the permanent position of a work in the vast catalogue of human culture.

One of the relations of the composer to his work will be the matter of technique, which on the lowest level constitutes merely craftsmanship, but on a higher level identifies itself with the composers thoughts. Seen under such light, his technique becomes a transmitter of aesthetic values. Accepting the fact that a musical composition is not only a work of genius and training, but also a product of environmental and cultural stimuli, one should easily understand the recent development of pure electronic music and of music in the electronic field in general. This is a historical necessity, regardless of our liking or disliking it. We know from experience that when the appeal is to universal suffrage, unanimity is not to be hoped for, but on the other hand we also know that any form of society which resists the capacity of man for progressive creative transformation is doomed. I am by no means a fanatic propagator or electronic music, but by the same token I do not accept any stubbornly rejecting opinions of people, for the most part based either upon ignorance or total disinterest in enlarging their vision of new possibilities of sound production and interpretation. Just think of the centuries needed for traditional music to develop and of the few years during which some experiments have been ma.de in electronic music. - Because every creative act overpasses the established order in some way and in some degree, it is likely at first to appear eccentric to most men. Let us not forget that it takes courage to face the unfamiliar, to associate oneself with the different - courage to fight one’s own prejudices no less than those of others. No doubt Freud was right in saying that men are strong so long as they represent a strong idea and that they become powerless when they oppose it!

In my opinion, electronic music should not be viewed as an eventual replacer of traditionally written music. On the contrary, they should be seen as two parallel blocks, between which co-existence should be perfectly possible. Let us not forget the abundance of somewhat more neutral and sometimes rather suspicious aspects of music flourishing today and serving a kind of mediator’s role between the main two music powers: any thoughts were directed towards the different types of aloeatory or chance music, musique concrète, multiple choice compositions and music to be improvised- (whatever that means!).

Another aspect or media or technique in use of contemporary composers is the combination of live sounds with actual instrumental and vocal sounds, but transmitted through loudspeakers. One of the purposes for this (speaking for myself) is the emphasis of the spacial aspect of music, obtaining a greater depth and also the juxtaposition between the physically present sounds and the ones coming from a different level. Of course this is simplifying matters because there are a multitude of problems being brought into existence with the use of this type of media, problems which open new possibilities, challenges, which give the composer a completely different insight into his work, opening many doors for discovery- and discovery is a very ambitious part of composition.

I don’t think I can describe my extraordinary experience, of having to tune myself not only on a “stereo” level but, on 4 different levels, while working on my last composition called “Quantetti” (short for “quatro Canti per Quartetto for Pianoforti”), - a composition for 4 pianos, three of which, previously recorded, will be broadcast through 3 loudspeakers placed in 3 different places around the concert hall -- while the fourth one will be handled on the stage by the exceptionally devoted performer of contemporary music, Mr. Leonard Stein. This is, of course, as part of the 20th Century Music Series on the last concert.

A basic quality is required from a composer -- today, as well as in the past, in order to determine his area of activity = complete honesty and integrity. A remarkable example in this regard was Arnold Schoenberg, from whom we can and should learn many among many things that [ Handwritten by Lazarof: Art begins where imitation leaves off.] In 1922 Busoni was reminding us that “Music was born free; and to win freedom is its destiny. Creative power may be the more readily recognized the more it shakes itself loose from tradition.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: unquote]

This should not mean that tradition is to be rejected -- on the contrary, history is present to help us point out that great innovations were always deeply rooted in tradition without being absorbed by it. -- A true artist is an interpretive artist, consistently devoting his life to the exquisite and enduring expression of his own individual reality in relation to his world. Time “filters out” the adventitious groups and relegates them to their proper places as entertainers and technicians for their own immediate time in their own immediate fashion. In his book, entitled “Composer’s World,” Hindemith points out the following:

“Technical skill and stylistic versatility have only one purpose: to bring into existence the vision of the composer.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: unquote]

I feel this is the most important aspect of composition, the only valuable relation between the composer and his world of sounds.

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: The result of it will be his experience and his organization of it, and that is what the audience will receive in the form of sounds.]

It is an impossible task to try to describe a composer’s vision and therefore senseless to explain his experience and his organization of it -- or his compositions.

One can always speculate upon a composer’s imagination, his inventions or discoveries,-- one can incessantly dissect a work, arriving at its most microscopic structures, isolating single sounds. One thing, however, will always escape our desire and perhaps need, and that is to understand the reason for existence of a musical composition and what it communicates to an audience. Understanding the structure of a work, its architectural conception means to grasp only one side, and perhaps the less important side of it. No analysis whatsoever, not even those furnished by the composer himself, can satisfy our eagerness to know the meaning of a work of art. Being essentially the instrument for his work, the co/lllposer is subordinate to it, and we have no reason for expecting him to interpret it for us. He has done the best that lies in him -- in giving it form and he must leave the interpretation to others and to the future.

The conclusion is that music can communicate anything and everything and the artist-creator has no jurisdiction whatever upon our experience and our reaction to his art. There are no grounds for meeting of minds and emotions between composer and listener. Our response will depend upon many factors: cultural background, musical sophistication, state of mind, power of concentration, all this will determine the speed of our grasping and reacting to a series of [ words crossed out] ordered sounds which constitute a musical composition. No logical procedures of any kind could be applied with success. No assumptions of any kind, so necessary in the world of sciences, can lead us to any meaningful conclusion. Our attitude will and should be determined only by the degree of exposure to music and our open mindedness about it.

Allow me to quote Picasso on the subject of communication:

“How would you have a spectator live my pictures as I have lived it? A picture comes from far off, who knows how far, I divined it, I saw it, I made it; and yet next day I myself dont see what I have done. How can anyone penetrate my dreams; my instincts, my desires, my thoughts, which have taken a long time to mature and to come out into daylight, and above all grasp from them what I have been about -- perhaps against my own will?”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: unquote]

A composition lives and changes only through him who listens to it.

Today -- as in the past -- composers are being strangely classified into two categories:- cerebral and emotional! Personally I have never understood the meaning of this. If by accusing an artist of being cerebral it means that he occasionally uses his mind and by glorifying another for being emotional it means that he does not make use of his scattered brain, then... well, its too bad! I .have never encountered in my life, an artist belonging to either one of these two categories. Let me quote opinions of artists on this topic:

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Beethoven in one of his letters (as quoted by Bettina Brentano) said: ]

“Rührung passt nur an Frauenzimmer (verzeich mir) dem Manne muss Musik Feuer as dem Geiste schlagen = ”Emotion is fit only for women -- for man, music must strike fire from his mind.”

Are we about to classify Beethoven as a cerebral composer? Beethoven’s genius was once attributed by Schubert to what he termed his “superb coolness under the fire of creative fantasy.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Stravinsky] in his “Poetics of Music” says:

“Art in the true sense is a way of fashioning work according to certain methods acquired either by apprenticeship or by inventiveness. And methods are the straight and predetermined channels that insure the rightness of our operation.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Unquote]

To which category shall we put the master of “Symphonie of Psalms” and of the “Rites of Spring?”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Eugine Delacroix]

“Art is no longer some sort of inspiration that comes from nowhere, which proceeds by chance and presents no more than the picturesque externals of things. It is reason itself, adorned by genius but following a necessary course and encompassed by higher laws.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Unquote]

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Picasso] “Art is what instinct and intellect can conceive.”

But artists being what they are, perhaps I should quote a different type of opinion by Carl Gustav Jung:

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: C.G. Jung] “Creative Process in its unconscious action has often been compared to the growth of a child in the womb. The comparison is a good one, as it nicely communicates the important fact that the process is an organic development, and it helps to dispel the notion that creation is simply an act of [ Handwritten by Lazarof: canny] calculation -- governed by wish, will and expediency.”

[ Handwritten by Lazarof: Unquote]

Cerebral, emotional, inaginative, inventive, speculative, charlatan, and a multitude of other adjectives have always been attached to the reputation of the composer. It is easy to see how this kind of subdivision and classification can lead us into real chaos.

Be he whatever he may be, the composer has always felt the need for order and organization which ultimately becomes an extension of his life. To absolutely every single phase of music history this sense of order has been evident- and today, perhaps even more than ever, this order is not just an elaboration of the established,- but a movement beyond the established,- or at least - a reorganization of it- and often of elements not included in it. The first need is therefore to transcend the old order. Needless to say, the composer should be well acquainted with what he is transcending!

On the other hand it is necessary for the audience to know that a composer composes to unload himself of feelings and visions, to combine and re-combine sounds, colors, rhythms, etc., [ crossed out: until desired feeling of relief. Concessions on the part of the creator towards the] until [ Handwritten by Lazarof: his] desired feeling of relief, [ Handwritten by Lazarof: not that of his audience is] attained. Concessions on the part of the creator towards the listener can only lead to mediocrity and artistic failure!

We see that musical composition is by no means a spontaneous phenomenae - but rather a process of change, of development, of evolution and organization. A great deal of the work necessary to equip and activate the mind for the spontaneous part of invention must be done consciously and with an effort of will.

The 20th Century being the “golden era” for the development of science, a scientific or quasi-scientific approach has been applied during the last few decades to music too. This was inevitable! Rather, surprising for me was the fact that it has stirred up a stormy reaction from a newly organized army of artists and scientists alike. Musicians feel offended in their most sensitive area -- pure, unadulterated emotions, while scientists despise the intrusion into their highly intellectual circles by artists. Personally I find this extremely amusing and must say I am having the greatest time reading articles, replies and replies to the replies- in several music magazines. The truth of the matter is that composers -- in their majority -- are not prepared to face a more or less scientific language, while scientists are overly anxious to prove that while A + B = C, C does not always equal A+ B because C-B may equal A, assuming that A-B+C-A could eventually give ABC and this will prove the relativity of the assumption!

There is no doubt that we are living in most exciting times! But I believe that what is happening is an illustration of the old Hegelian dialectic of processes in the motion of growth. When forces, with something opposite at stake, clash, out of their clashing comes something new, a new unity which negates what has gone before. This makes possible resolution of one conflict and either the beginning of a new one which gives, as conclusion, a feeling of the entire destiny and origins of the conflicting elements and conflicted characters, or a final determination of the combating opposites.

There is no doubt that in music today, with all the conflicts being created by the clash of old and new, with the new possibilities, and challenges offered by the development of science, there is a new expression taking shape, a new body created with the vision of men such as Schoenberg and others, a body acting as a powerful sound magnet continuously attracting new orbiting sounds created incessantly by a younger generation, which in turn, modifies the existing one in an attempt to enrich the centuries-long trasury of musical culture. It is pointless for us to stand in the way of such cultural progress, disliking it, rejecting it and fighting it in the name of tradition and old established values.

Sound is impregnated with space and time and its only value lives in the present and future. Sound in retroaction being merely a reproduction of an already existing one becomes stagnant, immobile and therefore unpurposeful and unnecessary. I firmly believe that the historical process of elimination will make itself felt in the years to come. To conclude, I would attempt to provide an answer to the haunting question of “how to acquire an attitude towards contemporary music” by saying that if in the [ Handwritten by Lazarof: past], our love, desire and need for music intrigued our curiosity for sounds, [ handwritten by Lazarof: today] perhaps the time has arrived to invert this relation and let our love for the sound per se, guide us towards a better comprehension and appreciation of the whole.

[ handwritten by Lazarof: Thank you!]

Radio Interviews

KALW’s Performing Arts Profile

Host: Alan Farley

Transcript

[Lazarof:]

Well, the creative process, which, for me, has become quite an enigma. Years ago, I thought I had it all clear in my mind, and having been a professor at university, I have been asked this question many times by my both undergraduate and graduate students, and from a pedagogical point, I tried to make it as clear as possible, but with time, it has become really impossible for me to talk about it. And I have found out the less I talk about, the less I try to explain, the happier I am because certain times, and fortunate I must say, more and more often, things are happening in spite of myself, so that I'm very happy not to have a clear idea of the creative process. Sometimes, it’s frightening because it’s in spite of me, and I feel that I have very little to do with it. However, no one realizes that we are a product of certain culture, needless to say an extensive training, and I have had that technical training, if one can call it technical, in many countries. So that’s very, very important, but of course, one takes this for granted. But as far as the creative process is concerned, I think that a composer is very much conditioned by the circumstances. If the composer receives a commission from a performing organization, it could be a soloist or chamber ensemble, symphony orchestra, and it depends how the commission is presented to the composer. It could be done very gracefully, very excitingly, and sometimes it’s really castrating. Because the conditions could be tough, could be difficult, and they could be altered, and sometimes a certain soloist is involved. And after the work is written, the soloist has been changed and somebody else steps in, and in the meantime, the conductor has resigned. (Henri chuckles) There’s a new music director, the orchestra goes on strike, a recording has been promised, and then you find out that the recording company has filed Chapter 11. (He laughs)

[Alan:]

It sounds like you've been through all of these things.

[Lazarof:]

But you see, you see that then the creative process disappears. It becomes the least important. That’s why I say making music is a physical matter. It’s much more interesting and important and exciting to deal with reality. So it depends how the beginning, how the composer is being approached. And in this case it has been very happy, and like every other work that was connected with the chamber orchestra, contemporary chamber players, it has been really a most gratifying experience.

Radio Interview with Lazarof

Host: Gene Peck

University of Utah, Salt Lake City

Transcript

[Lazarof:]

Of course, we know that all instructions on paper are very relative, for the simple reason that our means, our tools really belong to the past, Middle Ages, notation, for example. They are very, very relative, and it’s just a very vague of presenting the idea, the musical ideas. Therefore, the performer here has to deal, first of all, with the relative way of notation, and trying to interpret the very specific ideas. Well, it’s always helpful if the composer is around and tries to control this, but in many compositions, especially for example, Webern, absolutely every single note has its own dynamic markings, tempe, a way of producing the sound, attacks and what note. So if the performer is very, very careful, he'll be able to perform the way it’s written. There is no space there left for this pouring of the heart. Many performers try to perform contemporary music with the romantic sense of interpretation, which is false. And one cannot present, on the other hand, music completely dried. So what we were talking about, inspiration, is always, should be part of the performer. Inspiration or musicianship, perhaps, is a more, a more clear word.

[Pack:]

Well, is the composer inspired, ever, or is it just the interpreter who’s inspired?

[Lazarof:]

Again, it’s strange because last night, we, in a panel with Dr. Abravanel and Mr. Steinberg from the Boston Globe, we had this topic of inspiration. I really don't know the exact meaning of the word inspiration. If it means the satisfaction that the composer can have during few split of seconds, if this is inspiration, then I have been fortunate to have several of these split seconds in my life. If, on the other hand, it means a complete dissatisfaction, but the interpreter thinks that those are exactly the moment where the composer has been inspired, if this means inspiration, I have had great deal of inspiration. (both laughing) So inspiration, let’s put it this way, a composer always tries to do his best, to at least he is trying to reach the Mount Olympus of clarity, of order, because one can cheat the entire world, but well, you cannot cheat yourself. So you might as well face reality, and try to do your best.

KMPC’s Inquiry: A Quest for Answers

Guests: Henri Lazarof and William Hutchinson on the subject of Modern Contemporary Music.

Hosted by Larry McCormick. Produced by Jim Ward.

Transcript

[Interviewer:]

Music can speak for itself. And that certainly did, but for the sake of our discussion professor Lazarof what makes this selection. Cadence II for Viola and Tape modern or contemporary.

[Lazarof:]

It’s a difficult question. It’s simplicity. I hope that the only factor that makes it to modern contemporary is the composer himself. And since I live in our time, it has to be modern. The only other technicality that one can point out is that it makes use, it calls upon the use of some kind of electronics tape recording techniques which are more part of our time, the last 20, 25 years, I would say.

[Interviewer:]

Would some of the great classical composers in your opinion, have used the modern electronic devices had they been available to them?

[Lazarof:]

It’s long fetch speculation, I would say yes,

[Interviewer:]

Of course it is.

[Lazarof:]

But if I think of a person like Debussy for example, he’s a classical composer. I have very little doubt that a person like that in constant search or new scenarios, new possibilities would neglect to make use of electronics. When you speak of electronic, there is such a vast array of techniques in medias from synthesizers down to musique concrète and tape-recording and pushing buttons with a simple tape recorders and whatnot. So I'm quite sure that they would have made use of our times’ technical facilities.

[Interviewer:]

As a modern or contemporary composer have you ever been tempted to embellish some of the compositions of say Debussy or Saint-Saëns or maybe some going farther by Bach, for example with what’s available electronically today?

[Lazarof:]

As a matter of fact I have used, these goes 10 years back, 1962. I had written a work when we started the contemporary music series at UCLA, a work for four pianos for Mr. Leonard Stein. It was one live piano and three prerecorded. And because of psychological reasons, I would say. The musical psychological at the moment I had used a Bach Chorale, which was played on the piano and transferred to the four speakers which were placed in the four corners of the

concert hall. And little by little, the harmony was distorted so that the chorale came to a decay in a sense come to distortion end. So this was not embellishment but I took the liberty of using a masterpiece. Again, I repeat because psychological reason in a specific text of the chorale for my needs but embellishment no, then this would be entertainment.