Brandeis celebrates 50 years of African and African American studies

The weekend featured Angela Davis '65, Julieanna Richardson '76, H'16, Hortense Spillers, PhD'74 and more

Photo/Mike Lovett

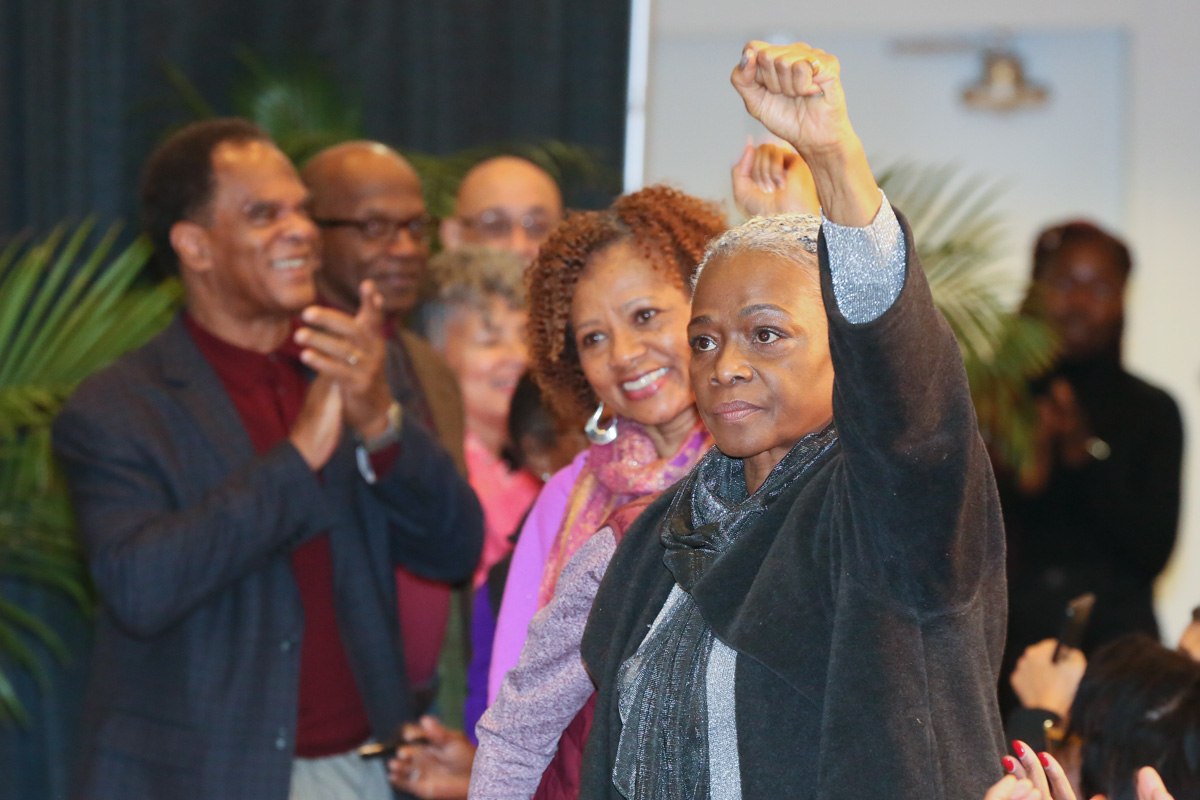

Photo/Mike LovettParticipants in the Ford Hall 1969 protests before a panel discussion.

Brandeis University recognized the 50th anniversary of its African and African American studies department with a weekend of discussions, performances and celebrations of esteemed alumni.

Literary critic Hortense Spillers, PhD'74, received the Alumni Achievement Award in a ceremony on Saturday, and a keynote address on Friday featured a conversation with activist and icon Angela Davis ’65 facilitated by Julieanna Richardson ’76, H’16. The events were organized by Chad Williams, Samuel J. and Augusta Spector Chair in History.

“The outpouring of love and affection that many of us experienced is something that I will personally never forget,” Williams said during an event Saturday. “It reminds us, more than anything, that the history of AAAS is about people. Beautiful, brilliant, courageous people who, from 1969 to 2019, have committed to this department through their work, teaching, scholarship and leadership. The ancestors are watching.”

Angela Davis returns 'home'

Angela Davis and Julieanna Richardson on stage.

In the Friday keynote, Davis described how her upbringing in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, and her high school years at Elisabeth Irwin High School in New York City influenced her views and activism. It was at Brandeis that she met an early mentor, philosopher and political theorist Herbert Marcuse. A Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of California Santa Cruz, Davis has published nine books during her scholarly career.

“I am so happy I came to Brandeis, because I think that when I discovered Herbert Marcuse, I discovered what I really wanted to do, and I didn’t know how to express it before,” Davis said. “I remember sitting in his lectures … I fell in love, not with philosophy per se, but philosophy as critical theory and as a way to think about the world, not in terms of what exists, but what can possibly be.”

Davis came to prominence as a political activist in the late 1960s, and her radical approach put her on the FBI’s most wanted list and led to her imprisonment in the early 70s. She pointed to her life experiences, particularly to the protests that led to her being freed from jail in 1972, as proof of the power of social movements.

"When people come together in that kind of united and concerted way, it is possible to thwart the plans of even the most powerful people in the world," she said.

Davis said it was important to cultivate what she called a long-range imagination, just as black people in the 1600s and 1700s who envisioned a world without slavery did.

“If people had given up on those dreams, who knows where we would be today,” she said.

Richardson, the founder of the archival oral history project, The HistoryMakers, said she had experienced many great moments connected to Brandeis — from receiving her undergraduate degree to delivering the Commencement speech in 2016 — but sharing the stage with Davis topped the list. It was the first time Davis had visited campus in more than 20 years.

“I can only say standing here in front of you, it cannot get better than this,” Richardson said. “She is home.”

Hortense Spillers: ‘It’s a tremendous surprise that we are here’

Provost Lisa Lynch and Hortense Spillers.

In presenting the Alumni Achievement Award, Provost Lisa M. Lynch praised Spillers as a “pioneering professor, feminist scholar and critic whose contributions have influenced the landscape of African American literary studies and advanced black feminist theory.”

In her keynote address, Spillers reflected on her participation in the 1969 takeover of Ford Hall by students dissatisfied with the racial climate on campus. “I was among the occupants of Ford Hall,” Spillers said. “I have always been happy I overcame what fear I had” in joining the 11-day occupation that ultimately led to the establishment of the Department of African and African American Studies.

Reflecting on the two-day celebration commemorating the 50th anniversary of AAAS, Spillers shared her enthusiasm for the progress that has been made at Brandeis in the field of black studies. “Fifty years later, it’s really incredible that we have come this far,” she said. “It’s a tremendous surprise that we are here … and that the program kept going and is continuing. That’s a genuine blessing and a wonderful thing to see.” Spillers also urged the wider adoption of black studies in higher education. “Are we bound for the day when black studies are everybody’s studies?” she asked.

Poet Askia Touré: in celebration of ‘the African pioneering soul’

Askia Touré and Kwesi Jones '21.

The commemoration events opened with a talk by Askia Touré, the poet, professor, editor and activist who was one of the founding members of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and '70s. Emilie Diouf, assistant professor of English, introduced him.

Touré celebrated the department’s longevity, noting that “whole generations of scholars, idealists, and freedom fighters gave their last full measure of devotion to resurrect before the planet Earth the African pioneering soul.”

He recalled his youth amid the turmoil of the late 1960s, and the assassination of leaders including President John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert, civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, saying “Oh, we were mad as hell. Some maniacs had killed our leaders and heroes.”

He read from several poems, including one extolling tennis players Venus and Serena Williams: “They are reality, not sanitized TV images; and millions of little girls, black, in all its implications—not "beautiful" as visualized by America and its blondes and wannabes—feel lovely, graceful, precious, empowered, inspired by the courtly deeds of these Nubian goddesses.”

Ford Hall: ‘You have to stand for something’

The Ford Hall 1969 panel in Levin Ballroom.

Participants in the 1969 Ford Hall protest took the stage at Levin Ballroom to recall the events that led to the occupation of the since demolished academic building, negotiations with then-president Morris Abram during the protest, and the aftermath of the protest. The students’ core demands were increased recruitment of African American students and faculty members, and the establishment of a permanent department for African American studies.

Participants in the panel included Hamida Abdal-Khallaq ’72; Randall C. Bailey ’69; Roy DeBerry ’70, MA’78, PhD’79; Ricardo Millett ’68, MSW’71, PhD’74; Vere Plummer ’74; Helen Stewart, PhD’80, and Patricia Van Story ’72.

Abdal-Khallaq recalled that arriving at Brandeis as one of only 13 black students in her class (a contingent considered large compared to previous classes), meant the 14-15-mile trip from Roxbury, where her parents were small business owners, seemed far more distant.

“It was like being on the other side of the world,” she said. “And that's why when we went into Ford Hall, most of us went in, we just felt like we had to go in because those were our people in there. We had to be in there with them.”

DeBerry was president of the Afro American Society at Brandeis, hailing from Jackson, Mississippi where he had been jailed for demonstrating in support of the Voting Rights Act. He recalled asking founding Brandeis President Abram Sachar for five MLK Scholarships in the wake of King’s assassination. Without prompting, Sachar doubled that number to 10. But the group of African American students who had negotiated with Sachar received a different reception from Abram, Sachar’s successor. He was “a different persona, a different person and the negotiation kind of got off on the wrong foot,” DeBerry said.

DeBerry said that a number of committees had been assembled to work on the African American students’ demands, but no changes resulted as 1968 turned into 1969. “Some bold action needed to be taken to at least get the attention of the officials,” he said. “That's the center of why we took over Ford Hall.”

Plummer, who was a Transitional Year Program student at the time of the Ford Hall protest, said he had been very grateful to attend Brandeis on a scholarship, but became disillusioned when high expectations weren’t met.

“We watched the leadership move and negotiate with the administration and there was a lot of activity. Each time we were expecting some progress, we got disappointment,” he recalled. “We wanted our own department. We wanted a chairperson who could hire and fire, we wanted black administrators, we wanted more black students, more TYP students, we wanted to build a black community here and we wanted to be able to be lasting.”

Patricia Van Story, who was tapped to be one of the negotiators with Abram, recalled how she became convinced to join the protesters. “At some point in time, in your life, you have to stand for something. You have to believe in something. And it may not go along with your plans that you have that day, or later in life, but you have to look at it, you have to step out of yourself and look at it. That's how I made my decision to support Ford Hall,” she said.

Categories: Alumni, Humanities and Social Sciences, Student Life