In the Kingdom of the Ancient Maya

Deep in the Mexican jungle, anthropological archaeologist Charles Golden, P’28, unearths remnants of a civilization of warriors, artists, and kings that still feels present and alive.

By Lawrence Goodman

Photography by Gaelen Morse

“Let’s stop here for a moment and imagine,” says Brandeis anthropology professor Charles Golden, P’28.

We are standing in a ravine in southern Mexico’s Lacandon Jungle. The temperature tops 100 degrees. Sonic waves of cicada song roll over us. Tropical birds squawk and screech incessantly. A few feet away, Maya stingless bees swarm around a honey-filled nest protruding from the base of a breadfruit tree. Leaves, burnt brown by the scorching June sun, crackle beneath our feet.

Wearing a Brandeis baseball cap and a green bandana around his neck, Golden, 51, points to a knoll in front of us. Buried beneath it, he says, is a pyramid. In 700-800 C.E., the ancient Maya would ascend a stairway to a temple at the pyramid’s top to offer gifts and sacrifices to the kingdom’s patron deity. Sculptural monuments lining the front of the pyramid were inscribed with hieroglyphics and depictions of mythological jaguars, serpents, and underworld gods.

Up on a ridge, where strangler fig vines coil around a stately ash tree, was a row of reception rooms and residences for nobles and other elites. There, sitting on elaborately carved stone benches in small vaulted rooms, society’s ruling class drank a bitter mix of ground cacao beans and water whipped into a froth, and ate richly sauced tamales stuffed with squash, deer, turkey, or iguana. Their headdresses, as befitted their high status, were adorned with the iridescent green feathers of the quetzal bird or the pink plumage of the roseate spoonbill.

Below us, on an outdoor courtyard, the Maya would perform choreographed dances, and play music on whistles, drums, and conch-shell trumpets. Artists, sitting beneath parasols, chiseled portraits of deities and monarchs on limestone stelae, alongside hieroglyphics that described their deeds for posterity. Potters fired vases, plates, and figurines, decorated with multicolored patterns, over burning coals.

Nine years ago, Golden and his longtime collaborator, Brown University bioarchaeologist Andrew Scherer, identified this site and the surrounding 100 acres as a major city in the ancient Maya kingdom Sak Tz’i’ (White Dog). Scholars had been searching for remnants of the city for two decades. It turned out to be hiding in plain sight, amid rubble and outcroppings on a cattle ranch.

So far, Golden and Scherer’s team has uncovered the remains of a palace; an acropolis; three pyramids; a ball court; numerous houses; 58 stone monuments; and a nearly complete skeleton of a middle-aged woman, dating from as early as 750 B.C.E.

Their work has only just begun. World-famous Maya sites like Chichén Itzá and nearby Palenque took nearly a century to excavate and reconstruct.

But when they were found, says Golden, gesturing at the overgrown jungle around us, “they looked just like this.”

Patience and perseverance

Federal Highway 307 runs north-south through much of the Mexican state of Chiapas, passing through stretches of dense jungle, milpa farms (a traditional method of sustainable agriculture), and rugged limestone hills.

It serves as a main route for Central American migrants headed to the United States. Families with small children trek on the roadside, asking for handouts of food and water at the tiendas and restaurants along the way.

For long stretches, there are no traffic lights, just topes — speed bumps. Warning signs are sparse and easily overlooked. Tourists driving at full speed over a tope send everyone in their car flying.

In 2014, University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Whittaker Schroder, scouting archaeological sites to research for his anthropology dissertation, slowed for a Highway 307 tope near the town Nuevo Taniperla. He noticed a carnitas vendor waving at him but thought the vendor was just saying hello. He kept on going.

The second time Schroder drove by, it became obvious the vendor wanted him to stop. He wasn’t looking to make a sale, though. He thought Schroder — like many American visitors during the summer off-season — might be interested in the ancient Maya. The vendor had a friend who knew about a Maya monument nearby. Did Schroder want to meet him?

Researchers in Chiapas are often told about Maya artifacts, which usually turn out to be souvenirs or fakes, or looted pieces. But the carnitas vendor was insistent, and Schroder finally agreed to go with him to see his friend.

When Schroder saw a photo of the monument on the friend’s phone, he knew he had to tell his colleagues Golden and Scherer about it. Right away.

Golden and Scherer first worked together in 1999, on a dig in Guatemala, just across the Mexican border. They hit it off immediately, sharing a similar intellectual intensity and a passion for late-’80s/early-’90s indie rock; science fiction; and micheladas, beer mixed with lime juice, hot sauce, and spices.

Four years Scherer’s senior, Golden began doing archaeological work in Central America when he was an undergraduate. As a summer intern on a field-school dig in Belize, he uncovered a small ridged tube he was sure was an ancient artifact. He rushed to inform his supervisor, who told him it was a piece of Kraft macaroni left over from someone’s lunch several weeks earlier. It was an early lesson on the dangers of jumping to conclusions.

“We both know that patience and perseverance is the name of the game,” Scherer says of his and Golden’s approach.

Brown University paleoethnobotanist Shanti Morell-Hart, who has worked with both men, says, “There’s this perfect symbiosis between them. They have an encyclopedic knowledge of the region and are always bouncing ideas off each other.” She calls their collaboration “one of the most successful in archaeology today.”

So far, the team has uncovered the remains of a palace; an acropolis; three pyramids; a ball court; numerous houses; 58 stone monuments; and a nearly complete skeleton.

In the 2000s, Golden and Scherer’s research focused on the kingdom at Piedras Negras in Guatemala. Sleeping in tents along the mosquito-ridden banks of the Usumacinta River, they unearthed remnants of the kingdom, which were accessible only by boat. The Maya had built glorious vaulted palaces; templepyramids; and sweat baths featuring heated rocks, masonry benches, and drainage systems there.

The two men also worked closely with Guatemalan refugees who had fled to the jungle to escape the country’s brutal civil war. The refugees served as guides in the jungle and helped out on excavations.

For Golden, the experience clarified what he values most about working in Mexico and Guatemala: “There’s amazing archaeology, but there’s amazing archaeology in many places,” he says. “It’s the people.”

As great as the ‘Mona Lisa’

A few weeks after Schroder showed them the photo of the Maya artifact, Golden and Scherer went to see it in person. They drove along Highway 307 to the town of Lacanjá Tzeltal, veered off onto a dirt road, and arrived at the home of Jacinto Gomez Sanchez, a cattle rancher, milpa farmer, carpenter, and convenience-store owner.

Sanchez’s grandfather moved to Lacanjá Tzeltal in the 1960s when the Mexican government opened the area to commercial development. Farmers and cattle ranchers rushed in, razing the jungle to clear pasture. Looters arrived, too. They scooped up Maya antiquities, untouched for centuries, lying amid rubble, and sold them to private collectors.

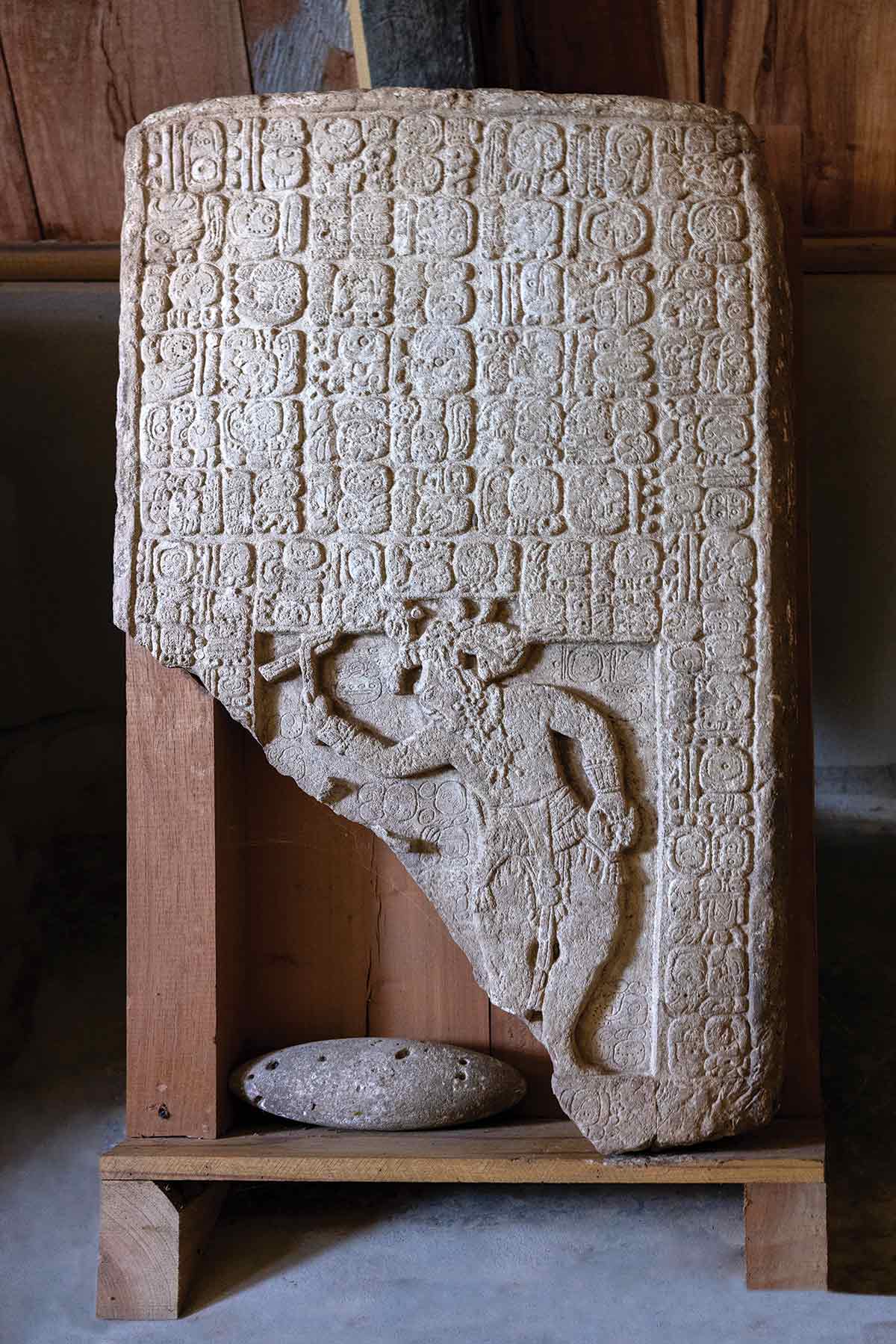

“I wanted to guard our heritage,” Sanchez says. So he built a wooden shed with a corrugated roof and locked some of the best-preserved Maya monuments on his family’s property inside. For years, he wondered what to do next. He finally talked to a friend, who enlisted the help of the carnitas vendor.

Amid ongoing regional warfare, the Sak Tz’i’ kingdom forged shifting alliances, craftily playing its enemies off one another to survive and thrive.

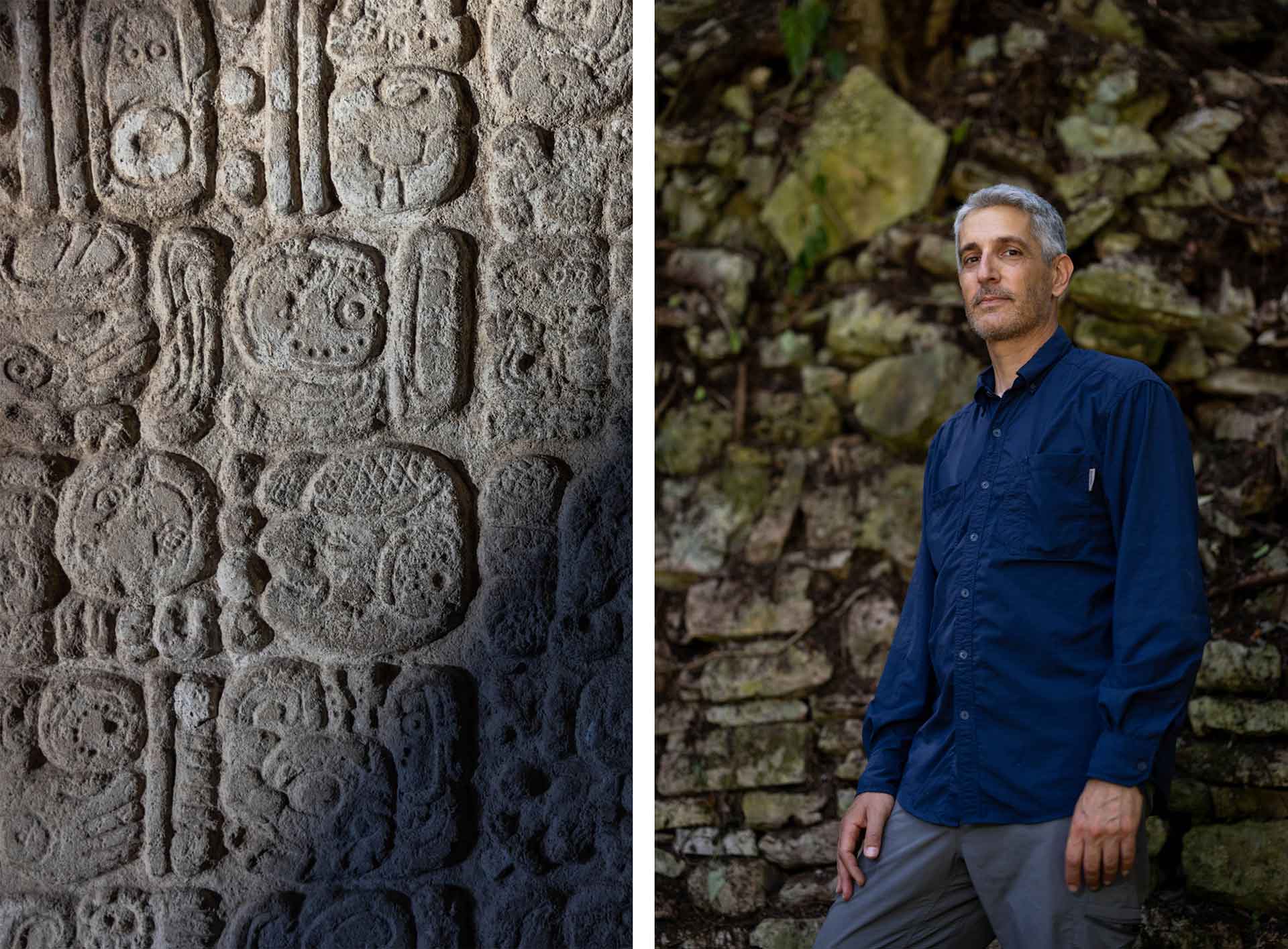

Golden says as soon as he entered Sanchez’s shed, he knew he was beholding “great pieces of art, great pieces of culture.” One limestone stela, about 4 feet high and 2 feet wide, particularly drew his attention. It is, Golden believes, as great a piece of art as the “Mona Lisa.”

The low-relief etching on the panel’s bottom half shows a king wearing a plumed headdress, dancing in celebration of a recent battle victory. His head is elongated. (A Maya infant’s head was tightly wrapped with cloth or leather, or bound to a board, to reshape the cranium. Most likely, this was done so the head would look like maize, a diet staple the Maya believed had spiritual powers.) The king wields an ax. In his other hand, he holds a ritual bludgeon. His wrathful, triumphant pose resembles the characteristic bearing of a Maya storm deity.

A piece of the monument below the bludgeon is missing. Judging from similar monuments found elsewhere in the region, Golden and Scherer believe it showed an enemy lord recently taken captive in battle. He would have been trembling before the monarch, no doubt aware of his likely fate; the Maya enslaved, tortured, or sacrificed their prisoners.

The top half of the stela contains hieroglyphics — a complex system of writing was one of the Maya civilization’s greatest achievements, along with its understanding of astronomy, mathematics, and architecture. Golden and Scherer spotted the glyph that is the emblem of the Sak Tz’i’ kingdom. Scholars weren’t sure where Sak Tz’i’ had been located. But the fact that the stela in Sanchez’s shed mentioned Sak Tz’i’ multiple times, boasting of generations of rulers and a military triumph, suggested it had been crafted within the kingdom.

Golden and Scherer asked Sanchez to show them where he’d found the monument. He took them to his cattle ranch, several miles away. Wading across a creek, ducking beneath barbed wire, and stepping clear of cow dung, they finally arrived at the base of a hill. Underneath that hill, Golden and Scherer realized, was almost certainly the ruins of a major building in the Sak Tz’i’ kingdom.

Later excavations by Mexican freelance archaeologist Fernando Godos González proved that hunch right. The building turned out to be a pyramid, originally around 45 feet high, fronted by a terraced staircase that led to a royal chamber with a throne bench. Supplicants would climb to the pyramid’s top to pay obeisance or beg favors from the Sak Tz’i’ king and queen.

Obsidian blades, grinding stones, bones

Golden and Scherer don’t like to say they “discovered” Sak Tz’i’, believing American outsiders shouldn’t get plaudits for revealing an ancient site well known to locals. Nonetheless, they are credited for locating the kingdom. According to Golden, it’s as if France had finally been filled in on a map of medieval Europe. “It’s that big a piece of the puzzle,” he has said.

It was another four years before Golden and Scherer could begin digging at Sak Tz’i’. They had to negotiate rights to excavate on the cattle ranch, a complicated dance between the Mexican government, Sanchez, and the larger community over who owns what’s unearthed and who might benefit from the tourism that results.

Golden and Scherer agreed to finance a local museum to house the Sak Tz’i’ monuments and other important artifacts, though, technically, they’re government property. The museum, a sturdier, more secure building than the original shed, is located next to Sanchez’s house.

In 2019, Golden and Scherer mapped the Sak Tz’i’ site using airborne LiDAR, a laser sensor that can penetrate the tree canopy to create three-dimensional models of the terrain. Sak Tz’i’ was a midsize kingdom with a population of around 1,000, perennially threatened by neighboring kingdoms. Sak Tz’i’ monarchs bore the title ajaw (“lord”), a step below mightier kings’ k’uhul ajaw (“holy lord”).

But, as The New York Times noted in a 2022 article on Golden and Scherer’s work, Sak Tz’i’ “punched above its weight.” Amid ongoing regional warfare, it forged shifting alliances, craftily playing its enemies off one another to survive and thrive. In a recent journal article, Golden, Scherer, and several other colleagues document how Sak Tz’i’ created a unique style of sculpture, melding elements from kingdoms as far as 60 miles away, suggesting it had wide interaction throughout the area.

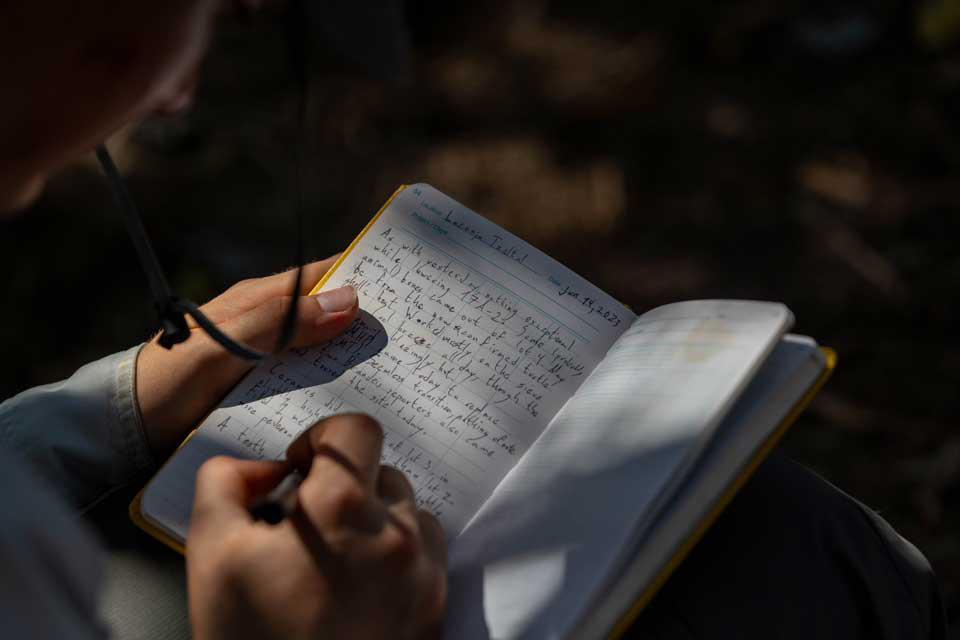

The search for remnants of the Maya city requires patience and meticulous attention to detail.

Today, even after 2,000 years of human activity and relentless natural forces, the presence of the Maya on Sanchez’s cattle ranch remains just beneath the surface of the soil. Pick up some rubble, and you’ll find obsidian blades, dart points, or straight-edged rocks for cutting and cooking. Look around a pile of boulders, and you’ll come across a household monument or a piece of grinding stone for maize. Dig a few feet down, and you’ll find pottery shards; Maya food scraps, in the form of animal bones or charred snail shells; or human remains.

The ancient Maya feel alive everywhere you look.

Golden, wearing moisture-wicking clothes, crouches by a recently excavated Maya grave, surrounded by open pasture. He has swapped his usual baseball cap for a wide-brimmed straw hat. It is unbearably hot again today, close to 104 degrees. He runs his hand along the sides of the crypt, rolls a bit of dirt between his fingers, and closes his eyes for a moment to think. Then he picks up and inspects a few rocks.

He’s wondering about who might have lived and died here.

A hardcore-geek passion for history

Brandeis doctoral student Van Kollias is digging with a crew about 10 miles north of the main Sak Tz’i’ excavation site, where he believes a competing kingdom’s exurb would have been located, or perhaps a frontier settlement unclaimed by any ruler.

Kollias takes what he describes as a “bottom-up” approach to studying the Maya, focusing on the daily lives of commoners, especially those who lived on the kingdom’s outskirts. “I want to know how people experienced a sense of belonging,” he says. “How did they interact with the surrounding political entities?”

He and his team have excavated a grave. The Maya buried their dead in their homes, and when it was time for a new home, they built it on top of their old one. Golden says the Maya believed each generation of inhabitants imbued their abode with spiritual energy, which accumulated over time. “Instead of charging their houses with electricity, they charged them with life,” he says.

Inside the grave, Kollias has found several greenstone beads, a few teeth, and fragments of long bones. Alongside the grave, he’s found fragments of plates and vessels, bits of obsidian blades, a half-dozen dart and spear points, and pieces of finely decorated pottery.

Cataloging and documenting these items, not to mention the excavation itself, has taken “an appallingly long time,” Kollias says. He asked Golden to come by and inspect the site. He had questions about interpreting the finds and whether he should keep digging here or move to another location.

“It’s your call,” Golden said in response. It’s the kind of thing a good mentor says — helpful in a way, but also a little bit not.

Kollias parks his truck far from the dig and carries everything he needs for the day on his back, as much as 75 pounds of stuff: pickaxes, trowels, notebooks, a carpenter’s rule, measuring tape, extra socks, sunblock, a rain poncho, a first aid kit, and lots and lots of water. He’s sweating, exhausted, frustrated, and (as he learns after he returns to the U.S.) in the early stages of dengue fever.

Today, even after 2,000 years of human activity and natural forces, the presence of the Maya remains just beneath the surface of the soil.

But he’s undaunted. “There’s nothing else I’d rather do with my life,” he says. He grew up in a Revolutionary War-era house in Ithaca, New York. He loved finding 18th-century glass medicine bottles while playing in the rubble of the original kitchen, hog pen, outhouse, and stone walls.

Others on the Golden and Scherer team report a similar hardcore-geek passion for history. “Were you an ancient Rome kid or an ancient Greece kid?” Grace Horseman, a 23-year-old field technician from Canada, asks her colleagues at a communal dinner one night. “I was an ancient Greece kid, but before that, I was a paleontology kid.”

Horseman has experienced frostbite while working in freezing temperatures in southern Ontario and now has a repetitive strain injury from day after day of digging in Mexico. “But it was my fault,” she insists. “I should have known better.”

Golden was entranced by history as a child, spending thrilling days in Chicago museums looking at artifacts from ancient Babylon and Mesopotamia. He majored in anthropology and history at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. When it came time to go to grad school, he says, he knew he “wanted to spend part of the time outdoors, digging holes in the ground.” He got a PhD in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Thomas O’Connor Golden ’28, Charles’ son, is also part of the team. He first joined his father on a dig when he was 9, the same year he sat in on a Brandeis class on osteology, the scientific study of bones. “I have been fascinated by bones ever since,” Thomas says. “Human bones, more than any other type of archaeological material, bring me closer to individuals, showing me how they lived and, sometimes, how they died.”

‘This is my excited face’

During their monthlong stay in Chiapas, Golden, Scherer, and their team leave the ranch-hotel that functions as their base of operations at 7:30 a.m. and work until 6 p.m., six days a week.

They stick trowels in the earth, dumping each scoop into buckets. The dirt is run through wire-mesh sifters. Clumps that don’t pass through are inspected. Rocks are discarded. Anything with the potential to be an artifact is brought back to the hotel, where it’s rinsed and inspected again.

Digging for bones, which are extremely fragile, requires even more care. One day, Thomas O’Connor Golden and two Brown graduate students spend four hours brushing the dirt off a small protrusion in the ground, which turns out to be an elbow.

“Archaeology can be tedious,” Charles Golden says. “Discovery takes decades. It doesn’t happen in one big breakthrough. It’s about moments when you feel the puzzle all coming together.”

At the end of one long day at the main excavation site, Felipe Gomez Sanchez, Jacinto’s older brother, who has been helping with the dig, spots something and hands it to Golden. As Golden inspects it, it’s impossible to know what he’s thinking. He is, by nature, private and reserved.

“It has been said that it’s hard to read my excited face,” Golden says later. “But this is my excited face.”

Sanchez has handed Golden a small shard of terracotta pottery. Across its bottom runs a streak of earthen red, a hallmark Maya color created by grinding ocher or cinnabar, adding water, then brushing the mixture onto clay. Once fired, the slip was slightly elevated and glossy.

This particular style prevailed between 200-600 C.E., the Early Classic period in Maya history. It’s the first evidence Golden and Scherer have found that people lived here then. It had been an open question: Was the city they are unearthing a capital or the capital of Sak Tz’i’. It was possible the Maya had moved the capital around.

But Golden and Scherer have now unearthed artifacts from before and after the Early Classic period, suggesting the site was continuously occupied for more than 1,500 years. “I am increasingly convinced the site was the capital,” Golden says.

Golden and Scherer have also wondered about Sak Tz’i’s influence throughout the larger Maya world. The Early Classic period was a time of widespread urbanization, as the Maya sought better economic opportunities, and proximity to wealth and power. If Sak Tz’i’s capital was inhabited during the Early Classic period, odds are it was a desirable place to live and, as Golden puts it, “a city of significance.”

He and Scherer don’t expect to unearth any major monuments or fine jewels at this dig. Looters have likely taken them already. But finding this pottery shard makes the whole day a success. “A missing piece of the puzzle fits into place,” Golden says.

Civilization and its contents

Golden leads the way across a mound of rubble covered with grass and weeds. This was once the Sak Tz’i’ palace. Several decades ago, the roof collapsed, likely because looters destroyed the building’s support structure.

“Look out for snakes,” he warns, though most of them aren’t poisonous. A bigger danger is spraining an ankle by stepping on a loose boulder.

As we head down the side of the mound, Golden stops at a small opening in the rocks. It’s pitch-black inside, so he turns on his phone’s flashlight and shines it inside. A room inside the palace comes into view. Limestone walls covered with stucco the Maya made from lime, sand, and water are visible.

Golden says the room’s ceiling was vaulted in the shape of an upside-down V. The room may have served as an administrative office, banquet hall, conference center, art workshop, or chambers for the royal family. Maya palaces were multifunctional, elaborately organized to regulate the interaction between the social classes.

Closer to the palace’s center, rooms were more opulent, off-limits to all but the elite and royalty. In some royal chambers, lords returned from warfare with tributes for the king and queen — anything from spicy chocolate to captives for enslavement or sacrifice.

The palace contained public courtyards where music and dance performances were held. Court jesters, often people with dwarfism, sometimes performed. The Maya believed those with dwarfism were connected to the underworld and possessed supernatural powers, and accorded them a special social status.

Blood-letting ceremonies probably took place at the palace. Blood played a central role in the Maya myth about the creation of humankind. Spilling it was thought to open a conduit between the natural and supernatural worlds. Sometimes, the rituals were relatively painless, involving a cut and a small splattering of blood. Other times, participants used obsidian knives, bone awls, or even poisonous stingray spines to perforate a cheek, an ear, a tongue, or a man’s genitals.

“Archaeology can be tedious. Discovery takes decades. It doesn’t happen in one big breakthrough. It’s about moments when you feel the puzzle all coming together.”

Charles Golden

Fascinating information about this complex civilization and culture may well lie amid the palace rubble. Golden and Scherer don’t know what’s there, because they haven’t begun excavating this area. There are many more years of work ahead of them at Sak Tz’i’, perhaps even decades.

But Golden is determined to complete the work. “We need to know what makes us human,” he says. “Every dig, every archaeological study gives us just a bit more of a glimpse into this critical knowledge.”