A Matter of Justice

Did the Jewish honor courts established after World War II punish Nazi collaborators fairly? Or did they revictimize Jews who had been caught in an impossible bind?

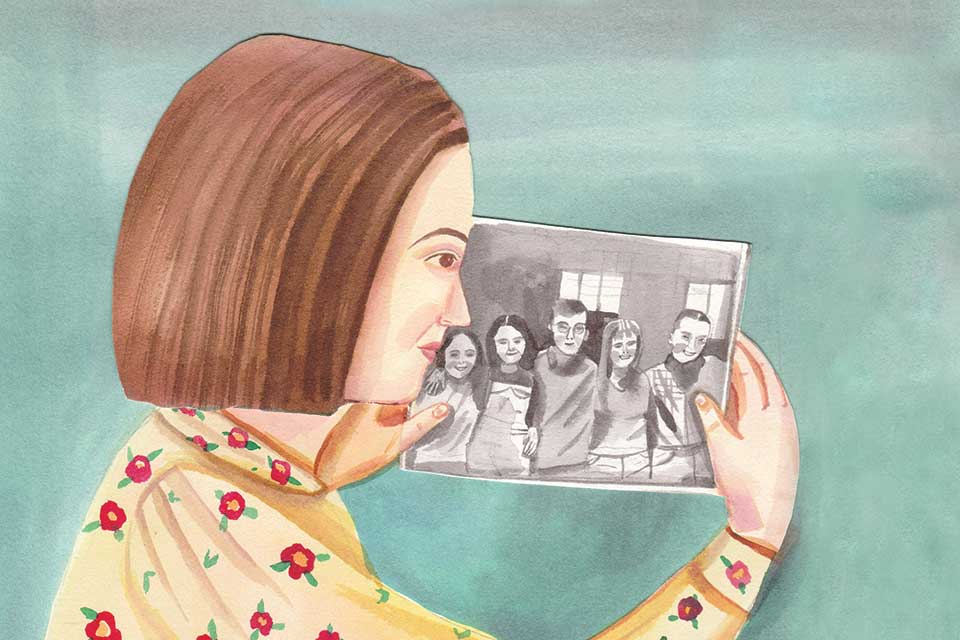

Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Museum, Courtesy Alice Lev

By Lawrence Goodman

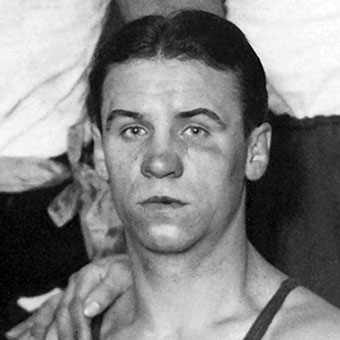

Shepsl Rotholc

“Rotholc Triumphs Over the Swastika” ran the headline in Sportcajtung, Poland’s Yiddish-language sports periodical, on April 30, 1934. Four years later, when Shepsl Rotholc, a Jewish featherweight boxer, bested another German contender, the paper was just as ecstatic: “Rotholc Beats the Nazi Boxer in Breslau!”

But after World War II, Poland’s surviving Jews had a decidedly different view of their star athlete.

During the Nazi occupation, Rotholc had worked as a policeman in the Warsaw ghetto, helping to enforce German orders. He beat other Jews, it was said. He ignored the pleas of a Jewish woman trying to escape a Nazi roundup.

So, after the war, a case against Rotholc was brought before a Jewish honor court. During the proceedings, he denied having brutalized other Jews. His defense lawyer argued that the “Jewish masses were subjugated to the most terrifying, infernal method of destruction” by the Nazis, and Rotholc had merely done what anyone else would likely do under the circumstances. He was just trying to survive.

In its judgment, the honor court found Rotholc to have “directly assisted in the extermination campaign against the Jewish people” and sentenced him to a two-year expulsion from the Jewish community.

Similar tribunals were set up throughout Europe to judge Jews who had allegedly collaborated with the Nazis. People brought before honor courts included survivors who had been informants; prisoners who had acted as Nazi functionaries at concentration, labor, or death camps; and those who had served on Judenräte, Jewish councils that helped administer the ghettos.

Laura Jockush (Photo credit: Gaelen Morse)

Laura Jockush (Photo credit: Gaelen Morse)

“There was a sense in the Jewish community that rebuilding after the Holocaust was only possible if these painful issues were addressed,” says Laura Jockusch, the Albert Abramson Associate Professor of Holocaust Studies, who studies how these courts operated.

Jewish honor courts were separate from military and governmental courts and the Allied military tribunals in Nuremberg. They weren’t state-sanctioned and had no power to pass criminal or civil judgments.

Instead, the Jews who sat in judgment used moral criteria to judge defendants, assessing their circumstances to determine why they did what they did and whether they had had any other choice. They handed down sentences in the form of moral reprimands, cuts in social welfare benefits from the Jewish community, condemnation as traitors, or excommunication. Sometimes the sentence involved imprisonment, even though the Allied military authorities prohibited detention, says Jockusch.

Traumatized and mourning lost family and friends, those who sat on these courts pondered profound questions of moral culpability. At what point had other Jews, themselves victims of the Holocaust, become complicit with the Nazi perpetrators? What were their transgressions? And what was a just punishment?

A structured outlet for anger

After the war, the Allies and the United Nations set up displaced persons camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy to house Eastern European refugees and the survivors of Nazi concentration camps. Of the millions of Jews persecuted by the Nazis, it’s estimated only 250,000-300,000 made it to a DP camp. They were known as the she’erit ha-pletah, Hebrew for “surviving remnant.”

Despite the overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and disease at the camps, residents showed “an almost obsessive desire to live normal lives again,” a UN official reported. They set up schools and theaters, and established newspapers. They held sports competitions. They celebrated weddings and religious holidays.

On Sept. 9, 1946, the newspaper at the Herzog DP camp, in central Germany, reported that “the Jewish committee has rightly decided, during one of its meetings, to create a citizen’s court.” The decision reflected a desire, the article said, for self-governance — when rules were broken, “such situations should be handled by us, and not by strangers.”

The Herzog court — made up of leaders in the Jewish community, some with legal experience — soon heard the case of Jakov Flayshheker, 23, who had been pressed into disinfecting bath facilities at a forced labor camp in central Poland, and was accused of beating and stealing from other prisoners. Flayshheker was convicted and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, then exile from the DP camp. He could return in a year if he “proves that he has acted for the good of the Jewish community and deserves to become a rightful citizen,” the court decreed.

Honor courts began forming in the largest Jewish DP camps. They also appeared in European cities to which Jews were slowly returning, trying to reestablish their lives.

Jockusch examines the rise and operation of the courts in a 2015 book, “Jewish Honor Courts: Revenge, Retribution, and Reconciliation in Europe and Israel After the Holocaust,” which she co-edited with University of Virginia historian Gabriel Finder. They estimate honor courts in Poland, Austria, the Netherlands, France, Germany, and Israel reviewed hundreds of cases and presided over several dozen of them.

Most of the courts stopped operating in the early 1950s. Some felt they had achieved their goal. In other instances, growing opposition to their work led them to shut their doors.

The courts had a historical precedent. They resembled the Jewish courts that operated in Europe from the Middle Ages to the end of the 19th century. Separate from the state, these courts were rooted in the Jewish community’s right to exercise limited self-government. They dealt with secular matters, such as the distribution of charitable funds or conflicts between community members. (Rabbinical courts handled legal cases related to Jewish law, marriage and divorce, and other religious matters.) Punishments included moral censure or excommunication.

In the wake of World War II, Jewish communities were searching for an orderly, humane, and just way to deal with the rage many survivors felt toward those perceived to have aided and abetted the Nazis. According to one witness who testified at Rotholc’s trial, the Jewish police in the Warsaw ghetto “were worse than the Germans.” Some observers believed angry Jewish survivors might be tempted to engage in vigilantism. The honor courts attempted to transmute that undercurrent of fury into thoughtful action.

Jewish complicity in no way compares to the roles played by Nazi perpetrators in the genocide, Jockusch says. But the anger that existed was real and “speak[s] to the deep sense of betrayal that survivors felt toward other survivors who had worked as prisoner functionaries or served on Judenräte.”

Shifting views on moral responsibility

In general, the honor courts made genuine, meticulous attempts to assess defendants’ moral culpability. They recognized that Nazis often forced Jews to collaborate.

At the same time, the courts didn’t necessarily exonerate individuals who said they were just following orders. They emphasized the importance of looking at an individual’s motivations.

In May 1947, a Berlin honor court heard the case of Martha Raphael, who had worked as a steno typist for the Gestapo at a temporary holding facility for Jews headed to concentration or extermination camps. She was accused of selecting Jews for deportation. Several witnesses provided counterbalancing testimony: Raphael had warned them about deportations; she had rescued a Jewish child.

The court ruled Raphael’s accusers exaggerated her importance in the deportation process. But it reprimanded her for speaking to fellow prisoners in a harsh tone and for using her secretarial work to get ahead. Her actions “signified an extraordinary emotional brutality, which was not officially required and which must be severely condemned from the perspective of a Jewish human being,” the court said.

Honor courts, Jockusch and Finder write in their book’s introduction, “generally judged harshly those individuals who raised suspicion that, after their recruitment by the Nazis, they had not reluctantly carried out their assigned tasks but rather had exhibited undue enthusiasm or even ambition.”

By and large, the trials were fair in their proceedings, Jockusch says. Defendants could defend themselves. Witnesses were presented. But the courts had blind spots.

Were the trials fair in their proceedings? By and large, they were, Jockusch believes. Defendants could defend themselves. Witnesses were presented. But the courts also had blind spots, she says. For instance, women were often judged according to gender stereotypes; some were found guilty because they behaved in ways that went against what was expected of them as women.

Then there’s an even larger question: Was it legitimate to put any Jew on trial?

For several decades after the war, Jews who had in some way helped the Nazis were widely condemned. In her 1963 book “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” historian/political philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote that the “role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.”

By the early 1970s, though, scholars’ views were shifting. It was increasingly clear that alleged Jewish collaborators often had no choice or found themselves in an impossible moral position.

“The term ‘collaboration’ is actually misleading,” Jockusch said in a recent address at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The term suggests a voluntary cooperation based on shared political goals, or shared worldviews and mutual benefits. That was not the case with Jews and Nazis during the Holocaust. Jews cooperated under duress, and never out of an ideological affinity with Nazism.”

So, did the honor courts go too far? Did their judgments victimize Holocaust survivors a second time?

The courts often displayed “a fundamental misunderstanding of the actual power relation between the Jews and Germans,” Jockusch says. “Part of the defining feature of the Nazi genocide was that the perpetrators used their victims — who were struggling to survive — to facilitate their work.

“That kind of complicity has nothing to do with the ‘nature’ of the victims, and everything to do with the goals and methods of the Nazi perpetrators.”

The pitfalls of passing judgement

In the 1920s, David Cohen was a well-respected papyrologist and classics professor in the Netherlands. He was also a prominent Jewish leader. He helped Eastern European refugees resettle in Palestine. When the Nazis rose to power in the early 1930s, he helped Jewish refugees flee Germany.

After the Nazis invaded Holland in May 1940, Cohen became co-chair of Amsterdam’s Jewish Council, responsible for implementing Nazi policies and regulations within the Jewish community. The record suggests the Germans forced him to take this position.

But once installed, Cohen proved highly accommodating to Nazi demands. In spring 1942, he endorsed the order requiring Jews to wear yellow stars, arguing that obeying the German authorities was the best way to improve their treatment of the Jews. A year later, after the Germans demanded Cohen identify Jewish Council employees for deportation, he and his council co-chair complied, personally checking off the names of 7,000 people. Almost all were eventually transported to concentration or extermination camps. Cohen himself was sent to Theresienstadt, outside Prague. Unlike most of the Jews whose deportation he helped arrange, he survived.

After the war, one of Cohen’s colleagues said he chose working-class Jews for deportation because he regarded them as more expendable than Jews from the upper classes. A high-ranking Nazi official said Cohen had asked for personal favors from the Germans, including the arrest of his son’s girlfriend, whom he disliked.

An honor court in the Netherlands tried Cohen in late 1947. He testified that, by acting in accord with Nazi demands, he had been attempting to avoid even harsher outcomes for the Jewish community he served. The court rejected this argument. It judged his actions “reprehensible,” contrasting his behavior with Jewish Council members who had rescued Jews from the Germans. The court banned Cohen from ever again holding a leadership position within the Dutch Jewish community.

Not everyone agreed with the verdict. Some Dutch Jews feared condemning one of their own would shine a negative light on the Jewish community and jeopardize its precarious position in postwar Dutch society. Others believed that Cohen’s trial had been rushed, that he hadn’t been given enough time to mount a defense. Increasingly, Dutch Jews came to oppose the honor court and wanted it disbanded.

In 1950, Cohen’s sentence was annulled. Until his death in 1967, he maintained he’d acted in the Jews’ best interest during the war, and even helped to save lives. But he remained something of a pariah, living his life in seclusion.

As a historian of the Holocaust, Jockusch doesn’t pass judgment on Jews who seem to have been complicit with the Nazis. Instead, she says, “it is about trying to understand what choices they made inside the genocide, with the limited knowledge of where Nazi policies were headed, with shrinking options, and with almost no room for maneuver.”

She continues, “There are implicit expectations of how victims ought to behave, expectations of self-sacrifice and communal solidarity. We expect them to have made the ‘right’ moral choices, but we tend to ignore the complexity of the reality they were facing, without the benefits of hindsight.”

Studying these people’s stories should take us to a place of humility, Jockusch believes. “They should leave us wondering, ‘What would I have done to save my family?’”