Perspective

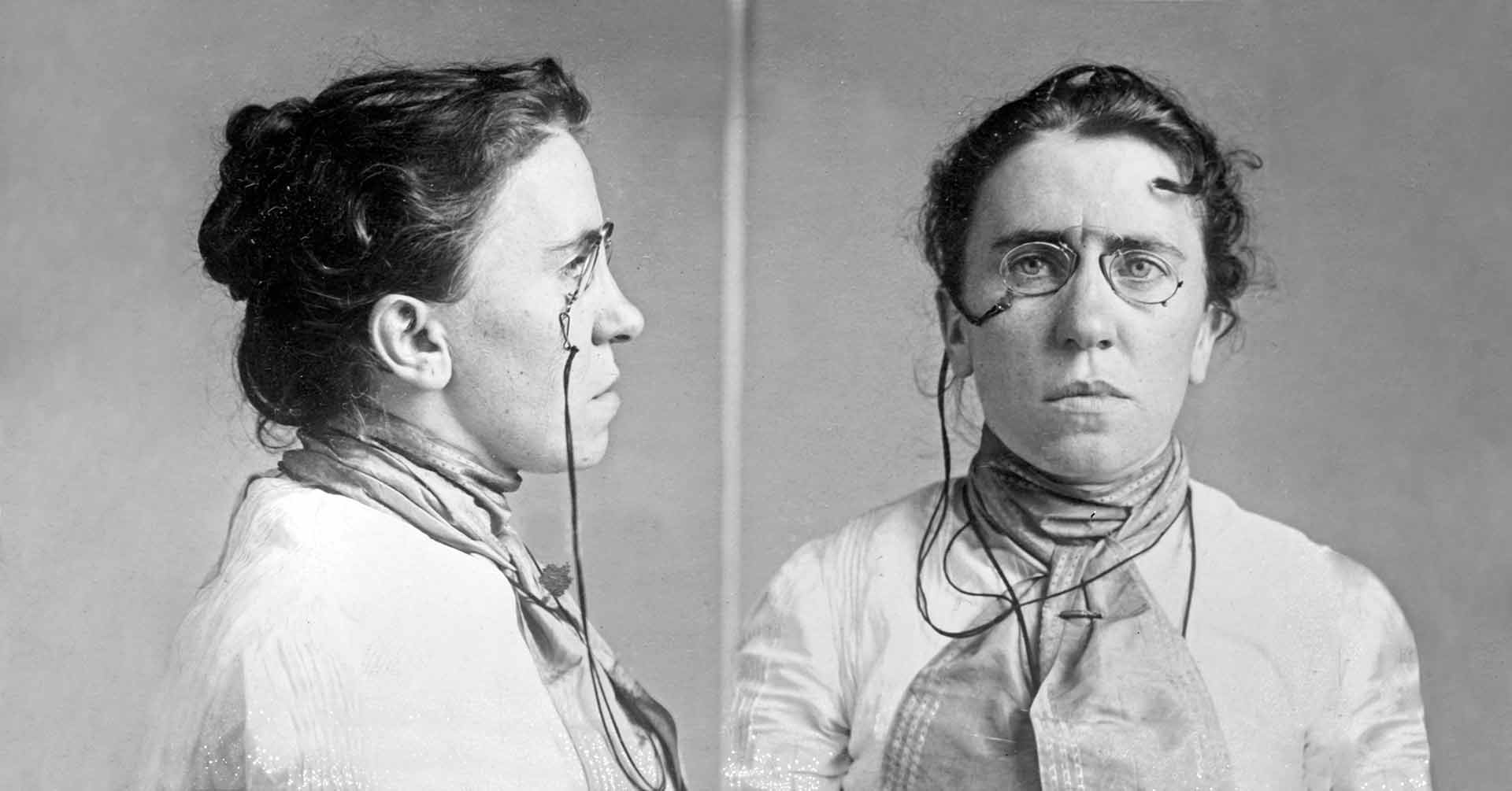

The Ghost of Emma Goldman

Today’s U.S. immigration crisis contains echoes of the American government’s “war against anarchy,” which branded migrants as racially inferior political threats.

By Michael Willrich

Amid a sweeping humanitarian crisis at the United States’ southern border, immigration is once again at the center of American domestic politics, and seems certain to remain so as the 2024 presidential campaign heats up. With legal immigration to the world’s richest nation barred to all but a lucky few, unauthorized migrants, as many as 9,000 in a single day, are making their way past barriers and razor wire to pursue economic opportunity in the U.S.

Republican governors in border states have made headlines by loading migrants onto buses bound for such cities as San Diego, Denver, and New York, where the migrants have overwhelmed shelters and social services. GOP politicians take the hard line, unleashing inflammatory anti-immigrant rhetoric and calling for a revival of the harshest Trump-era policies. Democrats have grown increasingly divided over how to tighten enforcement while building compassion for migrants into America’s dysfunctional immigration system.

In this moment, revisiting the anti-immigrant politics that gripped America a century ago is instructive.

Between 1900-15, 15 million immigrants arrived in America, most entering via the Port of New York (three-quarters of the city’s population consisted of immigrants and their children). It was the largest sustained wave of mass immigration the U.S. had ever seen. Many American political leaders denounced the “new” migrants from Southern and Eastern Europe as racially inferior, unassimilable “others,” the infectious carriers of radical “foreign” ideas like socialism and anarchism.

Many of these foreign-born workers became radicalized by what they experienced in America: exploitative labor conditions, nativism, and violent police repression of the labor movement. Some joined unions, like the radical Industrial Workers of the World. Some became socialists. And a small but fiercely committed number (roughly 100,000 by the 1910s) embraced the most radical ideology of all — anarchism.

Anarchism was a cosmopolitan, anti-authoritarian ideology. Like political liberalism and Marxian socialism, it was rooted in Enlightenment ideas, and shaped by the great economic and political transformations of the 19th century. Anarchists differed on questions large and small. But overlaying all the finer points of doctrine was a shared utopian belief that the world would be a better place without the most-taken-for-granted institutions of modern Western civilization: nation-states, borders, laws, religion, marriage, and private property.

As America’s most infamous anarchist, the Lithuanian-born Jewish immigrant Emma Goldman, defined it, anarchism was “the philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.”

In its efforts to crush the movement, the government confirmed the anarchists’ worst fears. American leaders had been denouncing anarchism as a foreign pestilence since they first became aware of the movement during the strike-riven 1880s, when four anarchists were hanged in Chicago for their alleged role in a Haymarket Square bombing that killed seven policemen. When President William F. McKinley was assassinated in 1901 by a self-proclaimed anarchist follower of Goldman, the nation’s leaders declared a “war against anarchy.”

Over the next two decades, the nation’s political leaders made the fateful decision to suspend its most fundamental principles and freedoms for the illusion of security. Disregarding the American anarchist movement’s origins in domestic social conditions, they vilified anarchism as an alien contagion. They imposed Draconian restrictions on free speech. They rewrote immigration laws to authorize the exclusion and, ultimately, the mass deportation of noncitizen anarchists, solely because of their beliefs.

They used the public’s fear of anarchy to justify an unprecedented build-up of domestic surveillance capabilities in the U.S. Department of Justice, led by a 24-year-old bureaucrat named J. Edgar Hoover. In 1919, officials at the Justice Department and the Bureau of Immigration hatched a plan to convert an Army transport ship into a “Soviet Ark.” The ship carried nearly 250 political prisoners — including the government’s principal targets, Goldman and her steadfast comrade, Alexander Berkman — to the Soviet Russian frontier.

If the nativism-fueled war against anarchy gave rise to the modern surveillance state, the anarchists left behind their own legacy, a vitally important one, as well. Although anarchists denounced the liberal ideal of the rule of law as a dangerous delusion — mere window dressing for capitalist domination of the working class — leaders like Goldman and Berkman were surprisingly astute and innovative legal strategists. Despite Goldman’s deep skepticism about the U.S. Constitution, she became one of the era’s most tireless voices for First Amendment rights.

In their fight against police repression, censorship, and the government’s deportation campaign, the anarchists helped give rise to the first generation of American cause lawyers. The civil liberties movement was in its infancy; the ACLU did not yet exist. Most of the young lawyers who defended “alien anarchists” were men and women at the margins of the legal profession, often immigrants or first-generation Americans themselves. Many were Jewish, denounced by casually antisemitic native-born leaders of the bar as “ambulance chasers” and “shysters.”

“Despite Goldman’s deep skepticism about the U.S. Constitution, she became a tireless voice for First Amendment rights.”

Goldman’s lawyer and close friend Harry Weinberger — the son of a Houston Street fruit peddler — defended her right to disseminate birth control information and speak out against the military draft. Weinberger also represented men and women detained after the infamous Palmer Raids, at their Ellis Island deportation hearings.

And he represented the young Russian Jewish radicals in the landmark Abrams case, which led Supreme Court justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis to issue a passionate defense of free speech, regarded by scholars as the foundation of modern First Amendment doctrine. In their dissent to the court’s majority opinion, Holmes and Brandeis declared the defendants, who had received prison sentences of 15-20 years for distributing antigovernment circulars on the streets of Manhattan, had as much right to print their leaflets as the government had to publish “the Constitution of the United States now vainly invoked by them.

The history of the long struggle between immigrant radicals and the U.S. government, from the dawn of the 20th century through World War I and the first Red Scare, reveals how an immigration crisis like ours can leave behind both dangerous and positive legacies. In the early 1900s, much depended on the political courage of a few people who stood tall against anti-immigrant hysteria and unaccountable government power.

Whether the current rising political storm over immigration leads to any positive outcomes at all will depend on the political courage of at least a few of our government leaders. It will also require the resolve of the American people to demand fair and humane treatment for the refugees and dreamers who, every day, arrive at our nation’s southern border by the thousands.

Michael Willrich, the Leff Families Professor of History, is the author of “American Anarchy: The Epic Struggle Between Immigrant Radicals and the U.S. Government at the Dawn of the 20th Century” (Basic Books, 2023).