Mining Pain for Wisdom

By Nadia Hashimi ’00

Nadia Hashimi (Photo Credit: Nahid Popal)

Part of Character Development

By the end of my first year at Brandeis, our group of newly minted friends was one fewer.

I can laugh at some of my undergraduate failures now, like the time I scored in the single digits on an organic chemistry exam (I did later redeem myself ). But my greatest college failure doesn’t show up on my transcript.

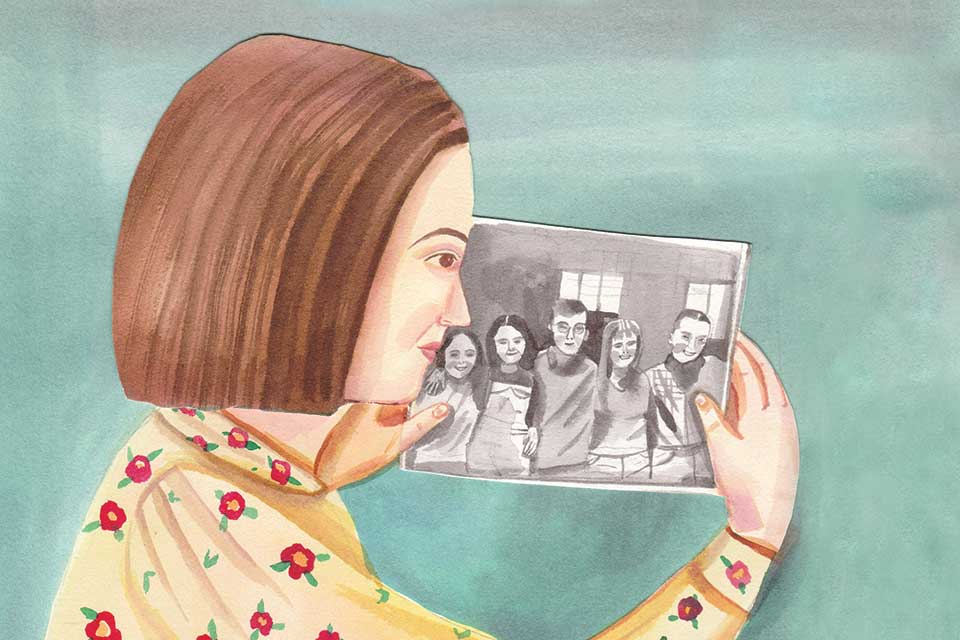

In a black-and-white photograph I have, I’m standing on the Pomerantz bridge with four friends. I’m the one in overalls. We are smiling against the sun. I don’t know what prompted us to capture this moment. We were likely on a study break, processing what we’d learned about covalent and ionic bonds. We certainly never imagined one of us would be gone soon thereafter.

I’m an unreliable narrator, so I’m not sure, but I believe we were in the cafeteria the day someone stood on a chair and bellowed the news that Robert had taken his own life.

In my hazy memory, the space went silent. So many smart people, collectively dumbstruck. In the days and weeks that followed, my head spun with questions. Why would Robert have made such a choice? What signs had I failed to see? How did I not sense his suffering?

His service was my first time in a Jewish temple, teeming with family and friends. “May his memory be a blessing,” I heard soft voices say. The words felt instructive and right. I pocketed the phrase.

Robert’s story is not mine to tell. I can say that the smile captured in that photograph was ever-present. He was a joy to be around. He listened intently. He seemed to have infinite patience while we struggled to make sense of stoichiometry. He was the gentlest spirit in our group, steadying our raft. Even in his absence, he made us more human.

“In the days and weeks that followed, my head spun with questions. Why would Robert have made such a choice? What signs had I failed to see? How did I not sense his suffering?”

Perhaps Robert had expertly concealed his struggles. Maybe he gave me no reason to be concerned. But because memory is a fuzzy, shape-shifting creature, I cannot be sure I should have been blindsided by the news of his death. Could I have nudged events in a different direction? It feels horribly pretentious to think so. I had known Robert only a few months. Other classmates were closer to him.

We are taught, collectively, that we can recognize a soul in crisis and prevent suicide, maybe with the help of a hotline or a hospitalization. Yet we are also told we should not carry blame or guilt when someone is lost to suicide. The cognitive dissonance tilts us left and right, leaving us dizzy and yearning for solid ground.

In school, my children are encouraged to embody a growth mindset, to know that failure can be replete with lessons. Did I miss an opportunity to connect with Robert in a way that could have changed history? Am I making the same mistakes now with others? I have wondered this as a pediatrician, sitting with families in crisis. I have wondered this as an author, as I explore the hurt and healing of complex characters. I have wondered this as a mother, especially as two of my children enter the cloudburst of adolescence.

When I write, I am often mining pain for wisdom. In one of my novels, a guardian comforts a child ensnared in mourning: “Grief is nothing but the far brink of love. Love is the sun; grief is the shadow it casts. Love is an opera, grief is its echo. […] But if you follow that grief, you will find your way back to love.”

I carry forward with me not the heartbreak that swirled around Robert’s departure, but the sunlit moments that defined his presence.

Beyond grief, the blessing is the brighter destination. Alchemizing a memory into a blessing requires intention. I try to mirror Robert’s grace. Listen intently. Steady the raft. Smile not only for pictures.

In the same way that failure is an inherent part of growth, loss is a certainty in life. We are fragile blooms in harsh gardens, drinking in the sun one day and wilting the next. May we all live and love in ways that will be a blessing, long after we are gone.

Physician Nadia Hashimi has written six novels, many of them focused on women’s lives in Afghanistan, including “Sparks Like Stars” (William Morrow, 2021).