On the Ramparts

By Ira Shapiro ’69

Ira Shapiro (Photo Credit: Jeremy Rusnack)

Part of Character Development

I came to Brandeis in September 1965. That beautiful autumn marked a rare moment in America — not long after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act — when peace, prosperity, and social justice seemed possible.

But President Lyndon Johnson had already decided to embark on an open-ended commitment of American troops to Vietnam, which would plunge the U.S. into years of political protest and domestic violence, shattering my generation’s youthful illusions.

And so my years at Brandeis were spent on the ramparts. My coursework coexisted with political action: marching on the Pentagon, working on Eugene McCarthy’s insurgent presidential campaign, coping with the fallout from the violence that attended the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

In September 1968, my friends Walt Mossberg ’69, Peter Alter ’69, and I conceived of an improbable independent-study project: a joint honors thesis on the current presidential candidacy of George Wallace. No one had ever done a joint thesis at Brandeis, but Gene Bardach, a young faculty member in the politics department, loved the idea and agreed to sponsor it. We got a $2,500 stipend from the Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence, which would cover some travel and research.

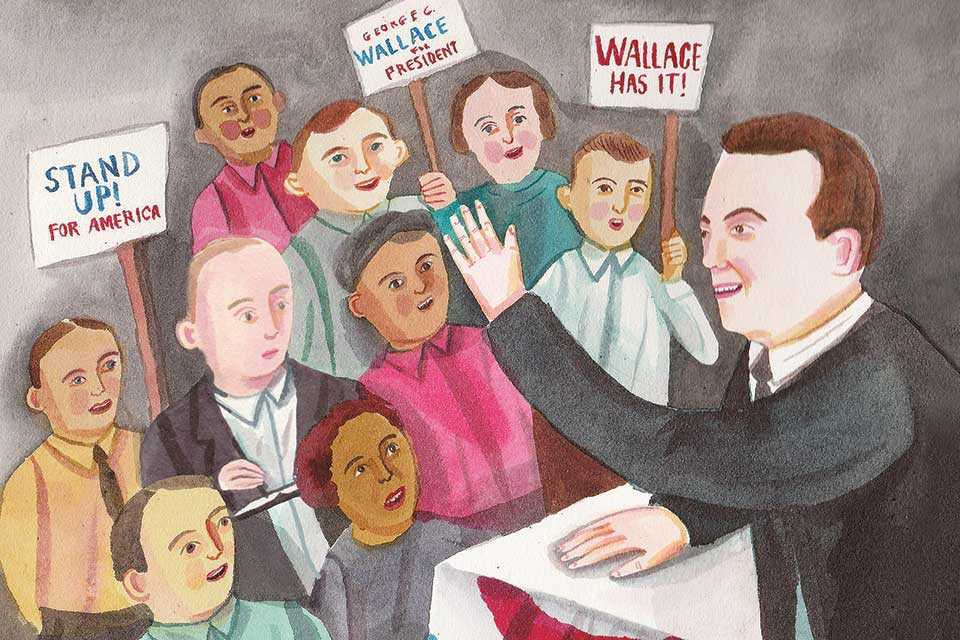

Walt and Peter spent time on the Wallace campaign plane. I visited the United Auto Workers headquarters in Detroit (I’d met UAW president Walter Reuther when he spoke at Brandeis). I wanted insight into how this progressive union was attempting to convince its members not to support Wallace, who was making inroads with his racist, populist appeals to disgruntled white workers. Then I flew to Chicago to attend a frenzied Wallace rally, where the former Alabama governor railed against busing and attacked “pointy-headed bureaucrats who couldn’t park a bicycle straight,” a phrase that predated “coastal elites” and “deep state.”

“When Walt, Peter, and I wrote our Wallace thesis, we honored the university’s credo, ‘Truth, even unto its innermost parts.’ The work deepened my passion for politics and government.”

In the November election, Wallace got 13.5% of the national vote — the strongest performance by a third-party presidential candidate since Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 — and won the electoral votes of five Southern states. UAW and other unions were able to coax most of their workers into the Democratic fold, helping Hubert Humphrey win Michigan and other Northern industrial states, though he lost the election to Richard Nixon.

In spring 1969, I visited Washington, D.C., to continue my research for our thesis. Increasingly intrigued by the U.S. Senate, which had emerged as a forum for challenges to Johnson’s and Nixon’s Vietnam policies, I attended a debate in the Senate chamber. Then I walked across Constitution Avenue to the office of Sen. Jacob Javits, a liberal Republican from New York, and applied for a summer internship, which, a week later, I got. The day after I graduated, I drove to Washington to become a Senate intern.

When Walt, Peter, and I wrote our Wallace thesis, we honored the university’s credo, “Truth, even unto its innermost parts.” The work deepened my passion for politics and government. In retrospect, we should have turned the thesis into a book — it would have taken a year or so to do — but we were eager to move on to the next stage of our lives. Walt became a reporter at the Wall Street Journal, then a trailblazer who quite literally founded the field of “personal technology” with his long-running column. Peter became a respected litigator.

My Senate internship showed me I wanted a role in formulating national policy. I worked 12 years in the Senate and almost five years in the Clinton administration, then practiced international trade law, then looped back to write about the Senate. The lessons I learned while working on our thesis informed my perspective on the challenges of governing. They also gave me an early understanding of Donald Trump’s frightening appeal.

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Holmes once described those who came of age during the Civil War this way: “In our youth, to our great good fortune, our hearts were filled with fire.”

My generation also grew up during crisis times. To a greater extent than anticipated, we find ourselves there again.

Lawyer and trade-policy consultant Ira Shapiro is the author of three books about the U.S. Senate, including “The Betrayal: How Mitch McConnell and the Senate Republicans Abandoned America” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022). He met Nancy Sherman ’69 on their first day at Brandeis; they recently celebrated 54 years of marriage.