Brandeis Magazine

The Art of Seeing Small

Using state-of-the-art light microscopy, Brandeis researchers examine biological processes once shrouded in mystery.

Courtesy Seth Fraden

By David Levin

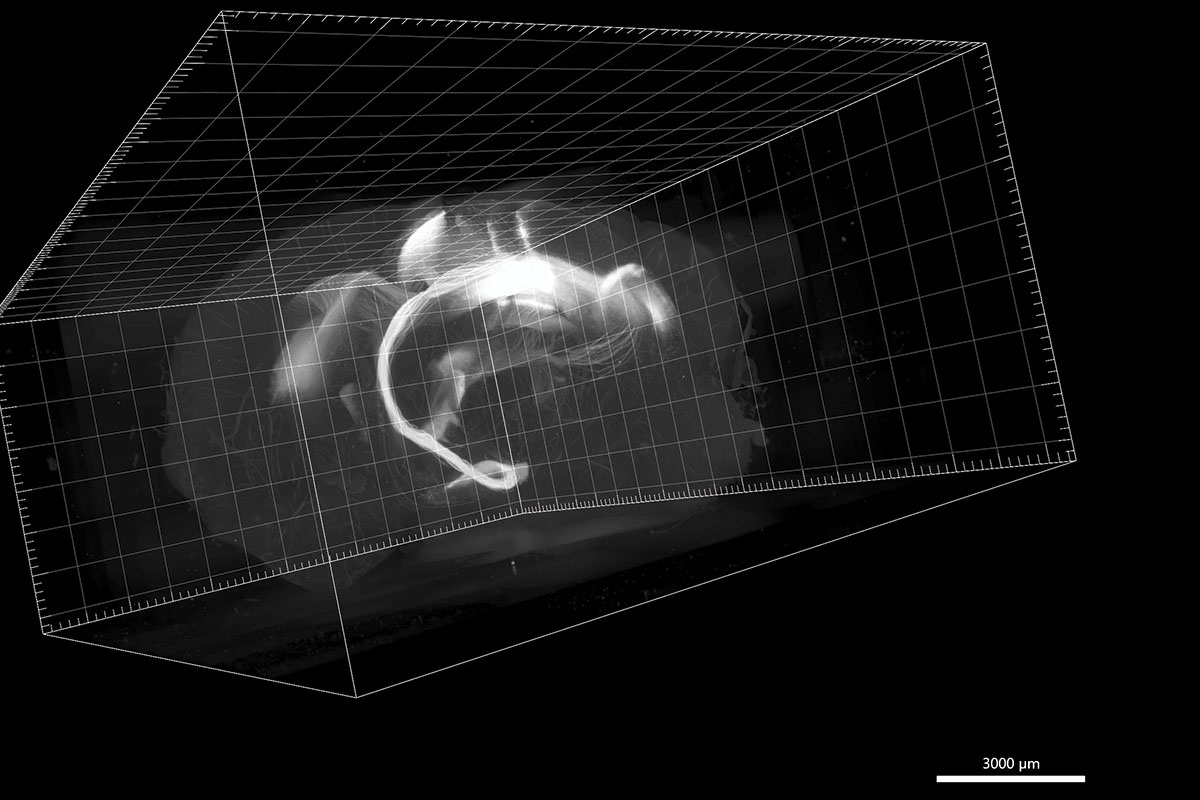

SPECTRAL PATHWAYS: Individual neurons connecting two areas in a mouse’s brain, shown in a light sheet microscope image.

Courtesy Christine Grienberger

In a corner of a dimly lit laboratory, Andy Stone brings up a ghostly image on a computer screen.

It’s a mouse brain, rendered nearly transparent, floating in digital space. Deep within its center, a cluster of fine tendrils glow faintly, stretching throughout the organ. These spindly filaments connect multiple regions of the animal’s brain, creating pathways that underlie the mouse’s consciousness.

Stunning images like this one, captured by cutting-edge optical microscopes, are helping scientists chip away at biology’s most tantalizing questions. How do memories form? How do proteins build themselves? How do cells sustain life?

Light microscopy instruments magnify complex worlds that were once impossibly small, giving scientists new tools with which to probe the natural world. Such ultrafine resolution doesn’t come cheap, though. A single scope can cost more than $1 million, out of reach for all but the most well-funded labs.

Stone has managed Brandeis’ Light Microscopy Core Facility since 2023. Working with university researchers, he’s transformed it into one of the best-equipped labs of its kind in the Boston area. He’s also democratized access to the facility, making its high-resolution scopes available to any Brandeis researcher who needs them, from faculty to undergraduates.

“Every instrument here represents good-natured, altruistic sharing of resources and expertise among its users,” says Stone.

This collective effort is already enabling bold scientific discoveries.

Much faster, much sharper

The facility has been a game changer for neuroscientist Christine Grienberger, an assistant professor of biology, who created the ghostly mouse-brain image. The instrument she used, a light sheet microscope, is one of Stone’s latest additions to his facility’s arsenal.

This device can scan a mouse brain with a thin sheet of laser light, then create a hyperdetailed 3D image of the brain. The technique represents a vast improvement in speed and resolution over older methods. Even just a few years ago, generating this kind of image required manually slicing a mouse brain into thin sections, scanning each one digitally and reconstructing those images into a crude 3D map. A single scan could take weeks or even months to obtain, and it might still miss key details.

The light sheet scope images an entire mouse brain in minutes. “It’s incredible, because we don’t need to do much computation to put it together,” Grienberger says. “We can just sort of see a video.”

Some of the real magic, Stone adds, happens before a mouse brain ever enters the scope. A nearby machine, roughly the size of a coffee maker, chemically removes carbohydrates and lipids from the organ’s cells, rendering its flesh optically clear. As the light sheet scope scans the now-transparent brain, fluorescently tagged cells glow faintly, revealing their position within its mass.

Researchers are able to see exactly how certain neurons are connected — clues to understanding how memories are physically encoded.

“The images we’re getting allow us to ask questions we couldn’t ask before,” Grienberger says. “And, beyond that, they’re also aesthetically gorgeous.”

Into the nanoscale

The light sheet microscope reveals biology’s architecture at the scale of organs and tissues. To push deeper — into the molecular machinery at work inside a single cell — the Light Microscopy Core Facility has instruments with even more powerful magnification.

Professor Seth Fraden, GSAS PhD’87, relies on the images these instruments provide for much of his research. A biophysicist, he studies protein assemblies, the molecular scaffolding that gives cells their shape and their ability to move and divide. These scaffolds don’t exist passively; they actively assemble themselves from individual protein molecules, following rules hardwired into the proteins’ chemical structure.

Understanding how the scaffolds form, Fraden says, might eventually allow engineers to design artificial nanoscale machines — tiny robots or other devices — that can build themselves without human intervention.

Step one is recording how the scaffolding process unfolds in real time. To do this, Fraden creates a simplified stew of the proteins, each tagged with a differently colored fluorescent molecule. As the glowing molecules combine and grow into long filaments, a confocal microscope tracks their movement in three dimensions over several hours. Like the light sheet scope, it gathers 3D images but at far-smaller scales.

While the confocal scope rapidly scans a thin laser beam through a sample, a pinhole weeds out stray beams of light that would otherwise blur the microscope’s field of view, providing crystal-clear images of samples just a few microns wide.

“Before we had access to this microscope, seeing those structures form was like seeing the sun through a hazy cloud,” Fraden says. “You knew something was there, but you’d get only hints of what was actually going on.”

Using the facility’s confocal scopes resulted in revelations, he says: “When you can actually see clearly, you find structure where you didn’t suspect any structure before. You get all kinds of surprises.”

For some biological questions, though, even that level of clarity isn’t enough. At truly tiny scales, light waves begin to physically interfere with one another, creating a fundamental barrier to magnification, known as the diffraction limit. It effectively restricts the resolution of conventional microscopes to around 250 nanometers — roughly three times wider than a single strand of DNA.

“When you can actually see clearly, you find structure where you didn’t suspect any structure before,” Fraden says. “You get all kinds of surprises.”

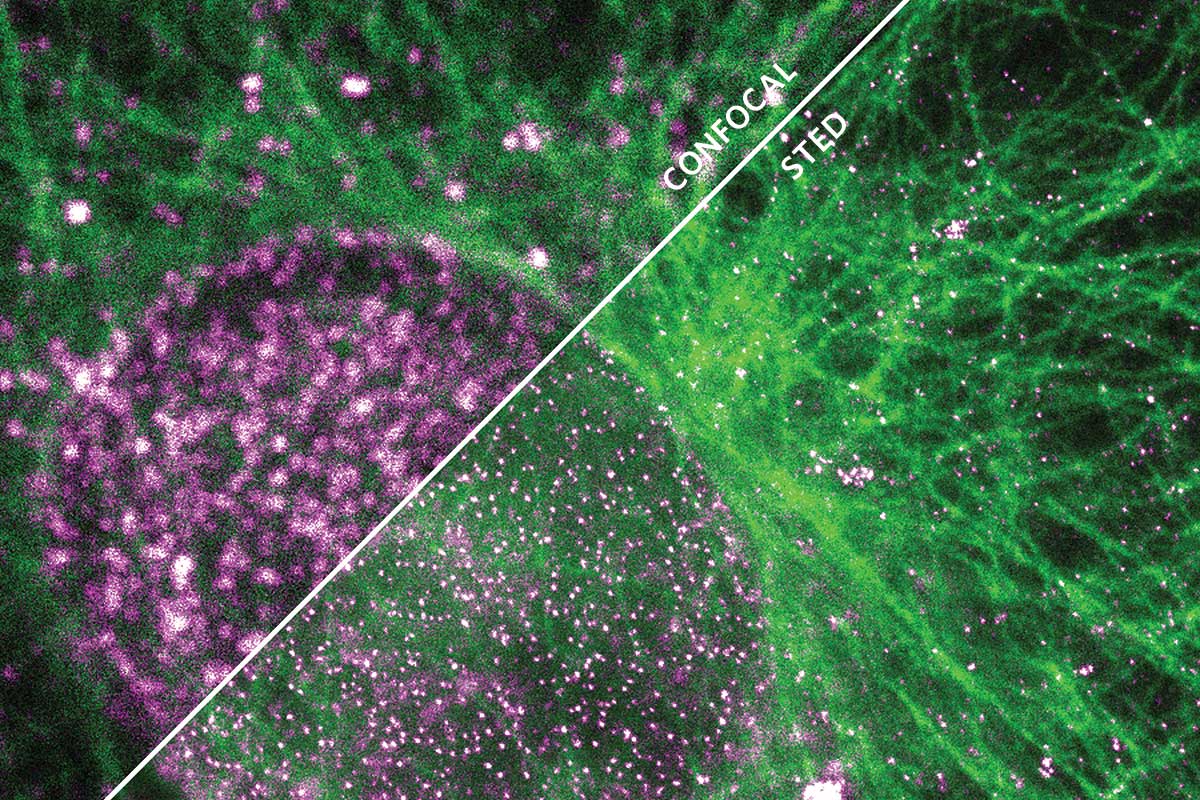

Steven Del Signore, a research scientist in biology professor Avital Rodal’s lab, needs to see past this barrier. He studies structures called vesicles, tiny packages that allow neurons to send and receive molecular signals. A vesicle is only about 50 nanometers across, well below the diffraction limit.

“With normal scopes, most vesicles would just look like blurry blobs,” Del Signore explains. “You couldn’t tell what was inside or outside the cell. You couldn’t count individual structures.”

So Del Signore relies on the facility’s stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope, which uses a clever arrangement of two lasers to break past the diffraction limit. The first laser beam causes the fluorescent proteins inside a sample to glow. The second beam, which looks like a doughnut-shaped cross section, then surrounds the first. When this pair of nesting lasers illuminates a sample, a neat trick of optical physics cancels out any fluorescent light occurring outside the doughnut hole.

Part of a family of techniques called “super-resolution” imaging, the process lets scientists see structures down to about 50 nanometers, roughly five times sharper than conventional scopes.

“That may sound like a small improvement on conventional scopes, but it’s actually transformative,” Del Signore says. “Instead of seeing a fuzzy blob, we’re seeing individual vesicles. That can mean the difference between getting a paper published or rejected. Right now, we’re basing an entire grant on the kinds of images we get from the STED scope.”

Courtesy Andy Stone

Harnessing the data deluge

To make use of the incredibly high resolution of the Light Microscopy Core Facility’s scopes, researchers have to capture an image onto a hard drive, a process that creates massive amounts of data.

A single scan from the light sheet microscope can generate 600 gigabytes of information. String together multiple scans, and a researcher might easily produce terabytes of data from a single experiment. Standard desktop computers can’t handle files that massive, let alone manipulate them for analysis (the maximum storage of most new laptops is 512 gigabytes).

To deal with the mountains of data, Stone recently installed a computer server the size of a chest freezer, connected by optical fiber to four high-powered graphics workstations. This kind of unseen data infrastructure is an essential component of modern microscopy. Without it, researchers could capture stunning images but would have no way to actually work with them.

“People always think about the microscopes, but they don’t always think about what comes after,” Stone says. “You need serious computing power.”

Investments in infrastructure have transformed what’s possible at Brandeis, and Stone is always thinking about new ways of improving his facility’s tools. He’s almost giddy as he describes the latest technology he’s testing: virtual reality goggles that let scientists “fly” through immersive 3D microscope images.

“It’s one thing to rotate an image on a computer screen,” he says. “But being able to put researchers inside an image completely changes their perspective. The data instantly become much more fluid and intuitive.”

The scale of the facility’s capabilities — and Stone’s drive to keep innovating — is already drawing researchers from across campus, and even scientists from local biotech firms, who pay to use the facility’s tools. But Stone says the real measure of success isn’t reputation or revenue. It’s access.

As he speaks, he pulls up another image — the delicate branching structure of a single neuron within a mouse brain. Just a decade ago, capturing an image like this required equipment available to only a few elite scientists. This one was created by a Brandeis undergraduate.

“That’s really what this is all about,” Stone says, his eyes drifting back toward the glowing neuron on his computer screen. “We’re not just buying expensive toys; we’re removing barriers.

“Every week, someone comes in here and sees something they’ve never seen before — and that opens up 10 new questions we didn’t even know to ask.”