Brandeis Magazine

Future-Proofing Higher Education

President Arthur Levine ’70 talks about Brandeis’ efforts to reimagine the liberal arts for the emerging global digital knowledge age.

By Laura Gardner, P’12

Photography by Dan Holmes and Gaelen Morse

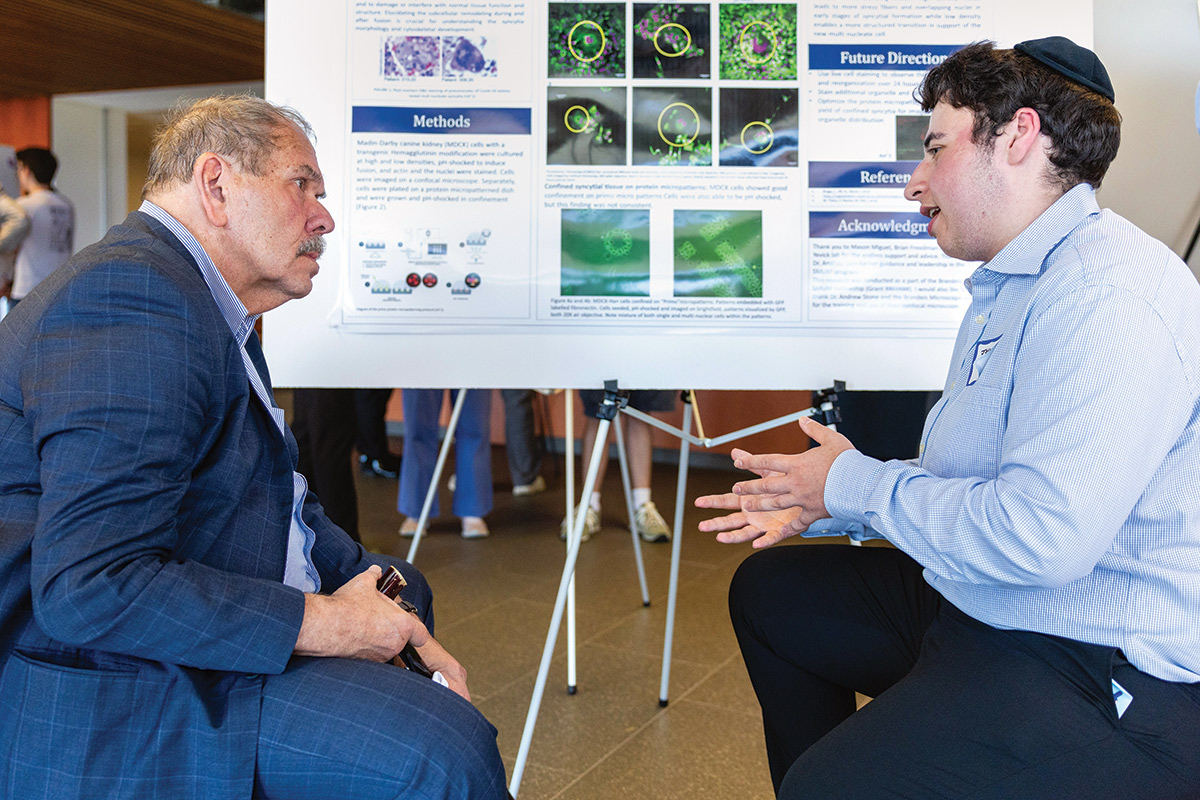

Arthur Levine ’70, who became the interim president of Brandeis in November 2024 and was officially installed as the university’s president the following September, has been a leading voice in American higher education and a fierce champion of the liberal arts for decades.

A first-generation college student who studied biology at Brandeis, Levine often notes how he has benefited throughout his lifetime from a liberal-arts education. That’s one reason why he is outspoken about the crossroads Brandeis and other universities face today. If higher education doesn’t adapt to the new digital knowledge economy, it risks becoming irrelevant, he believes.

During his career, Levine has led Teachers College at Columbia University (1994-2006) and the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation (2006-19), and he’s written 13 books on how institutions respond to social change. His 2021 book, “The Great Upheaval: Higher Education’s Past, Present and Uncertain Future,” co-authored with Scott Van Pelt, traces how technology, globalization and demographic shifts are disrupting higher education just as profoundly as the Industrial Revolution did.

The challenge for universities, Levine argues, is nothing less than to reinvent a model built for the Industrial Age into one ready for the digital era. Colleges and universities must move to an outcomes-rooted focus, from one-size-fits-all degrees to a mosaic of credentials, certificates and lifelong-learning opportunities. And amid all this change, he insists, universities must hold fast to enduring values of excellence, access and service.

Following the success of “The Great Upheaval,” Levine and Van Pelt teamed up again to write “From Upheaval to Action: What Works in Changing Higher Ed,” due out in March from Johns Hopkins University Press. This book shifts from diagnosis to prescription, spotlighting how institutions are experimenting with new approaches to elevating teaching, ensuring career readiness, expanding affordability, improving student life and dealing with political pressures.

Levine’s leadership of Brandeis draws on deeply personal ties. He is quick to point out, in conversation and public appearances, how Brandeis changed his life, giving him lifelong friends, a family, a fulfilling career — and a first-rate education. “Brandeis allowed me to make a two-generation mobility move,” he says. “I didn’t realize any of that at the time, but it opened up all kinds of careers I never could have expected to have had.”

Here, Levine reflects on his Brandeis experience, the seismic shifts in higher education and his vision for the university as an education leader over the coming decades.

You grew up in the South Bronx. How did you find your way to Brandeis?

I grew up in the deep South Bronx. My mom finished high school but not my dad. But, from the day I was born, they told me I was going to college. When it came time to apply, we didn’t know how the process worked. Neighbors suggested good schools. People in my building said Brandeis was the best college in America, while people across the street said Notre Dame was. Since I was Jewish, I applied to Brandeis. That’s how I ended up here.

What was Brandeis like when you were a student?

It was an extraordinary cultural change for me. I didn’t know anyone else who was first-generation. The saving grace was that so many of us were Jewish — that gave us something in common. Brandeis gave me lifelong friends, and introduced me to my wife and a profession. It also gave me a sense of warmth and family in the midst of national turmoil — Vietnam, civil rights, constant demonstrations.

What was it like to return as president in 2024?

Surreal. The last time I had been in the president’s office was when we occupied the building during a protest. So it’s very odd to come back as president. I found a student body that is probably intellectually stronger and much kinder than in my day, and a faculty that remains remarkable. Brandeis still feels like a family — warm, close and committed. It was like falling in love with the university all over again.

What mandate did the Board of Trustees give you?

The board asked me to do three things: Choose the direction Brandeis should move in for the decades ahead, write a job description for my successor and help them choose that successor.

How did the faculty respond to your mandate?

I told the faculty I’d be here for only two years — whether I was the best or the worst president in Brandeis history. [Ed. note: The Board of Trustees has since asked Levine to serve through June 2027.] That honesty helped me ask for their trust and partnership. I shared the broad outlines of a plan to reinvent the liberal arts and asked them to fill in the details, and, after months of meetings, 88% of the faculty voted in favor of it. That kind of unity is rare — you usually can’t get 88% of faculty to agree that tomorrow is Friday.

Faculty told me they wanted to remain a world-class research university. They wanted to remain one of the top liberal-arts colleges in America. They wanted to retain our heritage, to retain the wishes of our founders and their dreams. They wanted to stop talking and act.

You’ve called the liberal arts both practical and essential. Can you explain?

The liberal arts have always been most successful when they’ve had one foot in the library — the accumulated knowledge of humanity — and one foot in the street, in the real world.

In Colonial America, Harvard taught Greek, Latin, Syriac and Hebrew, not because the neighbors spoke those languages, but because leaders needed those skills. Today, the liberal arts provide enduring competencies — communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork — that matter even more in a world of constant change. Specific job skills may fade, but these life skills are enduring.

Why does Brandeis need to reinvent the liberal arts?

The education our students need now is not the education their parents needed. We are moving from a national analog industrial economy to a global digital knowledge economy.

Every social institution is being transformed, and higher education is no exception. Today, we’re seeing new providers — Google, Coursera, cultural institutions like museums and libraries — offering education. The American Museum of Natural History is now offering PhD and teacher-education programs. As many as 20-25% of colleges may close, and others will look more like online degree programs. The wealthiest universities have the time and resources to wait before acting, but schools like Brandeis must lead.

How is Brandeis reinventing the liberal arts?

Content has a shorter half-life than ever before in history, so we will focus on the competencies, the skills, the knowledge that will take our students forward. We’re creating a competency based curriculum focused on durable life skills needed in a digital knowledge economy — communication, critical thinking, adaptability, creativity, collaboration.

The irony is, in a world that wasn’t changing as quickly, students would still need these things. They were very important skills to have in the past. Now, they’re imperative.

What, specifically, is different about this new curriculum?

Every student will have both an academic adviser and a career adviser from day one. We’re building a Center for Careers and Applied Liberal Arts to connect students with internships, alumni mentors and real-world experiences. We’re also creating a second transcript to record the competencies students demonstrate, with help from the Educational Testing Service, one of the most highly regarded assessment firms in the world. And we’ve reorganized into four new schools — integrating arts and sciences with applied fields like business, policy, engineering, technology and culture.

You’ve also talked about creating a “skunkworks,” an experimental lab that tries out new pedagogical methods.

Yes, we’re going to apply AI and virtual reality to career exploration and pedagogy.

What is the role of experiential learning in this new model?

It’s critical. Internships and applied experiences allow students to put their liberal-arts skills into practice in the real world. That’s why we’re emphasizing experiential education and creating a second transcript to document not just courses taken, but competencies demonstrated.

How does this second transcript work, and why does it matter?

Traditional transcripts list courses and grades. The second transcript will list competencies and job-specific skills aligned with careers. For example, a student preparing for journalism might show competencies in writing, interviewing and research. It gives graduates a portable record of what they can actually do, which is what employers and grad schools want.

Some alumni might worry this career focus risks turning Brandeis into a vocational school.

There’s a name for colleges that don’t change: museums. We’re not abandoning the liberal arts — we’re embracing and applying them. We’re holding fast to Brandeis values while giving students the tools they need for the world they’re entering.

How is Brandeis positioning itself against rising competition from corporations and online platforms?

Wealthy research universities have the luxury of waiting and validating what others have done. Brandeis doesn’t. We don’t have time or money to waste — we need to lead. Reinventing the liberal arts positions us as a model for the future rather than a follower.

What role can alumni play?

A huge one. We want alumni to share their extraordinary careers with students, as advisers, mentors and connectors. We have graduates who are CEOs, Nobel Prize winners and leaders in every field. They can show students how to navigate careers while keeping Brandeis values at the center. Alumni will also see Brandeis in the news for leading change — their pride will draw them in.

“The liberal arts have always been most successful when they’ve had one foot in the library — the accumulated knowledge of humanity — and one foot in the real world.”

What do you hope alumni and the broader public will see in the coming years?

They’ll see tributes to Brandeis for leadership in higher education, for bold innovation and for shaping a model that others follow. Alumni will feel proud of their alma mater and be invited to share their careers and expertise with students, deepening their engagement with Brandeis.

Where will this take Brandeis over the next decade?

I believe Brandeis will be recognized nationally as a leader — like Brown in the 1960s or Northeastern more recently. We’ll be known for pairing liberal arts with real-world application. Applications will rise, alumni will be more engaged, and the media will see us as pioneering a model for the future. In short, Brandeis will become a hot school.

What would Justice Brandeis think of this transformation?

He lived during the Progressive Era, when abuses committed by American industrialists needed reform. He believed education was essential for democracy and social justice. I think he would applaud what we’re doing — remaining true to Brandeis’ mission of repairing the world while adapting boldly to the needs of a new era.