Professors Michael Rosbash and Jeff Hall honored at Nobel Prize ceremony

Nobel committee lauds laureates for explaining “an essential mechanism for survival of life on the planet.”

Photos/Associated Press

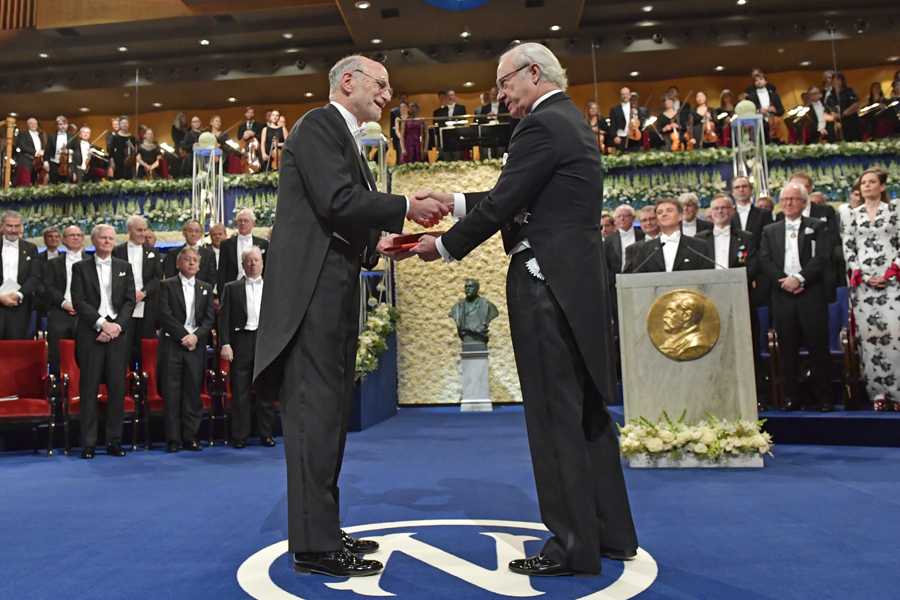

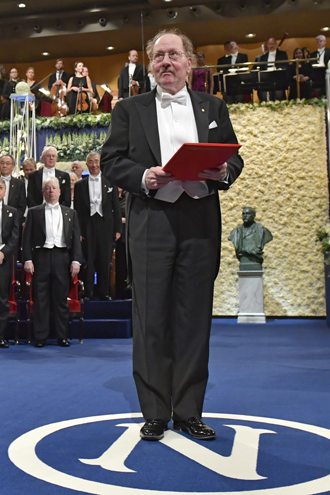

Photos/Associated PressMichael Rosbash receives the Nobel Prize medallion from Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf. Below, Jeff Hall stands on the stage in Stockholm.

|

For complete coverage, visit our 2017 Nobel Prize page |

It’s official.

From the hand of Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf, Brandeis professors Michael Rosbash and Jeff Hall each received an 18-carat gold medallion as recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the world’s most prestigious award for achievement in the life sciences.

They shared the prize with Michael Young of The Rockefeller University, who was also on stage to receive a medallion. All three achieved foundational breakthroughs in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that run the internal biological clock in almost every organism on the planet. Rosbash is the Peter Gruber Endowed Chair in Neuroscience, and Jeff Hall is a professor emeritus of biology.

In a dazzling ceremony steeped in protocol, Carlos Ibáñez, a member of the Nobel committee which selects the winners of the prize in physiology or medicine, introduced the three laureates and described the impact of their research.

“The 2017 Nobel laureates have uncovered the mechanisms controlling truly fundamental processes in physiology — how our cells and bodies keep time,” said Ibáñez, a professor in molecular neurobiology in the Department of Neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute. “Professors Hall, Rosbash and Young, your brilliant studies have solved one of the greatest issues in physiology.”

First Hall, followed by Rosbash and then Young, walked to the center of the blue-carpeted stage, stood on a huge “N” emblazoned on the carpet, and shook hands with King Carl XVI Gustaf. Each recipient bowed three times: first to the king; then to previous laureates and prize committee members; last, to the audience.

For Rosbash, 73, who has enjoyed prominence and phenomenal success in the sciences since he began his career 40 years ago, the award cements his place as one of the most important biologists of his generation. For Hall, 72, who retired in the late 2000s and has lived in seclusion in Maine ever since, the prize reaffirmed his relevance and importance in his chosen field of genetics.

“We have been blessed with good fortune at almost every turn,” Rosbash said in a speech at the banquet that followed the ceremony. “Yet to have this journey topped off in this way is almost unimaginable. Mike, Jeff and I are honored beyond words.”

Rosbash also reflected on the endangered state of the sciences and rising xenophobia in the United States. This year, President Trump broke with a nearly 20-year-old presidential tradition of meeting with America’s Nobel laureates before they travel to Stockholm.

“Although it continues to be the essential foundation for progress in more applied areas, the current climate in the U.S. is a warning that continued support cannot be taken for granted,” said Rosbash.

“Also in danger is the pluralistic America into which all three of us were born and raised after WWII,” he continued. “Immigrants and foreigners have always been an indispensable part of our country, including its great record in scientific research; eight of the 10 Nobel science-winners here today are U.S. citizens, but four of us are immigrants or children of immigrants. We are changing this successful formula at our peril.”

The ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall had the feel of a coronation mixed with Academy Awards glamour. Men donned black tails and the women wore glittering evening dresses. The Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra played selections from Mozart and Bach. It was broadcast live on Swedish TV as commentators interviewed guests.

The awarding of the physiology or medicine award was accompanied by the song cycle, “Liebesbriefchen” (“Love Letter” in German) by the American composer Eric Wolfgang Korngold and sung by Swedish soprano Camilla Tilling.

The ornate floral arrangements on the stage included 661 pounds of flowers chosen to suggest winter in Sweden. In the middle of the stage stood a floral wall of 9,000 roses, carnations and chrysanthemums in white and cream-colored hues. As in previous years, all the flora came from Sanremo, on the Italian Riviera, where Alfred Nobel, who created the prizes, spent the last years of his life.

Guests included the royal family, representatives from Sweden’s parliament, the Swedish academics who choose the laureates, and the winners of this year’s other Nobel Prizes. Hall and Robash’s families and Brandeis President Ron Liebowitz and his wife, Jessica, also attended.

After the ceremony, the festivities moved to Stockholm City Hall for a banquet. The laureates and other featured guests entered in a procession accompanied by a fanfare of trumpet and organ. The guests began on a balcony and proceeded down a staircase decorated with flower garlands directly to the table of honor.

They sat at a long table of honor in the center of the room, surrounded by roughly 1,300 other guests. The table was laden with a bed of flowers resembling driven snow. Attached obelisks of ice slowly melted like a thaw on a sunny winter day.

The evening’s menu, prepared by Sweden’s master chefs and kept a closely-guarded secret until the banquet began, included dried Jerusalem artichoke served with kohlrabi flowers flavored with ginger and lightly roasted cabbage broth; crispy saddle of lamb; potato terrine with Svedjan crème; yellow beet, salt-baked celeriac, apple salad and rosemary-spiced lamb gravy; and for dessert, frost bilberry bavaroise, bilberry ice cream with lemon thyme, lime jelly, lime curd and lime meringues.

According to the seating plan, Rosbash sat diagonally across from his wife, Nadja Abovich, and directly across from Urban Ahlin, speaker of the Swedish Parliament. Hall sat across from Ishiguro Kazuo, this year’s laureate in literature.

The banquet was scheduled to end around 11 p.m. Swedish time, followed by dancing upstairs in the Golden Hall, a gold-painted room with mosaics on the wall inspired by events and famous people in Swedish history.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology