Build the Wall? The Maya did it over 1,000 years ago

President Trump isn't the first to think about a fence along the border. Anthropologist Charles Golden has found remnants of Maya border walls from over 1,000 years ago.

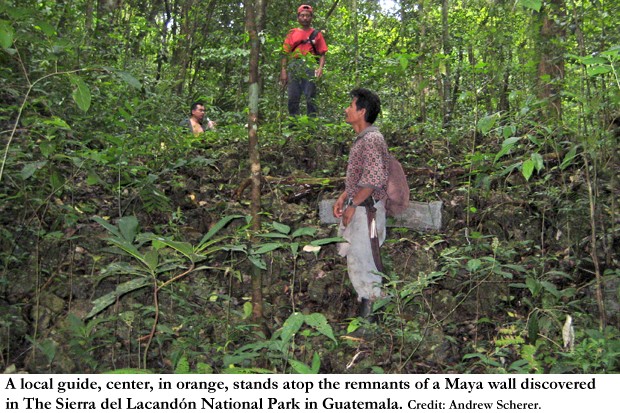

Credit: Andrew Scherer.

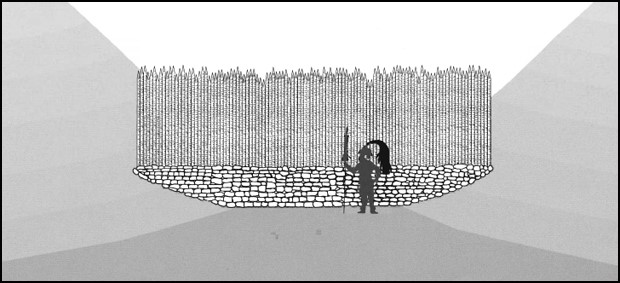

Credit: Andrew Scherer.The walls consisted of a row of stakes resting on a stone foundation.

President Trump wants to build a wall along the Mexican border. His controversial effort is the latest in a long history of societies building barriers to define territory and protect themselves from outsiders. The practice was part and parcel of the civilization of the ancient Maya.

For over a decade, Associate Professor of Anthropology Charles Golden and his colleague Brown University bioarchaeologist Andrew Scherer have been researching the walls the Maya built in the eighth and ninth centuries in southwestern Guatemala. Their excavations have uncovered barriers and barricades throughout the region.

They served to demarcate the boundary between two Maya kingdoms, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan. The walls were a modest affair by Trumpian standards, consisting of a wooden palisade resting on a pile of uncut boulders and reaching a height of roughly eight to 12 feet. But they were critical to defense and tell us a lot about how the Maya thought of themselves and their enemies.

Golden and Scherer think the inhabitants of Yaxchilan built the walls to protect themselves from invading Piedras Negras warriors in the 8th century when warfare between the two kingdoms erupted.

Golden and Scherer think the inhabitants of Yaxchilan built the walls to protect themselves from invading Piedras Negras warriors in the 8th century when warfare between the two kingdoms erupted.

Each segment of the barrier ran across a valley between two nearby foothills. Attackers would not have tried invading by climbing the foothills because their opponents would have been able to stand at the top and rain down weapons on them. This made protecting the flat land absolutely critical.

Sometimes there were gaps between portions of the wall where people could pass through. Here the Maya built a system of gates. If attackers managed to get through the first set of gates, they entered a “kill zone,” or empty space where they were completely vulnerable. And if they survived the kill zone, there was yet a final portal they had to break through.

As primitive as it may sound, it was an ingenious way of permitting passage through the walls if the Yaxchilan wanted to come and go while at the same time making it very difficult for Piedras Negras soldiers to break through.

Golden and Scherer also found evidence of settlements atop the foothills. Each one had a watchtower where the Yaxchilan could keep lookout. They used slings and stones and throwing spears as weapons, or could hurl heavy rocks downhill. Meanwhile, they sent smoke signals to alert soldiers and residents far away of an impending attack.

It may have been these walls — or at least the need to man them — that led to the decline of the Maya empire. As kingdoms expanded, the monarchs delegated the responsibility of protecting the borders to noblemen.

Gradually, the nobles usurped more and more responsibilities from the king. They even sponsored their own markets and religious festivals. At some point, people asked themselves why they needed the king when they had the local nobles.

There may have been other causes for Maya decline — internecine warfare, drought, exploitation of natural resources and foreign invasion, among others — but by the 9th century, its heyday was long over. For all the effort that went into building and defending them, the walls fell into disuse and crumbled. The fate of Trump’s wall remains uncertain.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology