From Grimm to Sondheim

Public domain

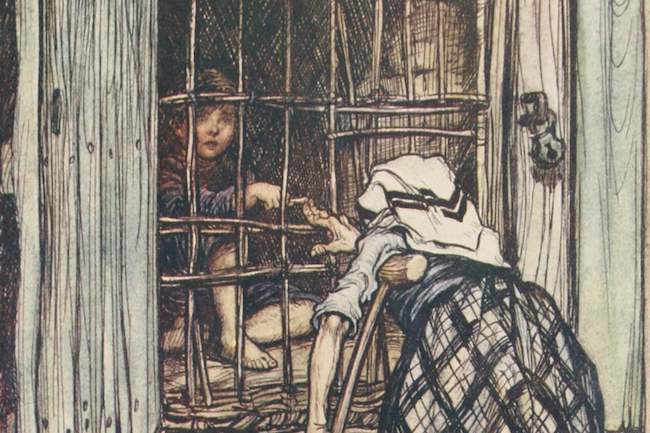

Public domainAn Arthur Rackham illustration of Hansel and Gretel.

Note: The Brandeis Department of Theater Arts' production of "Into the Woods" is slated to run March 16 to 18. Tickets can be purchased online, by phone at (781) 736-3400, and in person at Shapiro Campus Center. This article originally appeared in the most recent issue of State of the Arts. Sabine von Mering is a professor of German, and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, and director of the Center for German and European Studies.

My first introduction to the Brothers Grimm fairy tales took place shortly before my fourth birthday, in a theater in Oldenburg, Germany. “Hänsel und Gretel” was the production. It was also my first time seeing a play. And my reaction became family lore for many years.

Even from the second balcony, I was terrified by the giant shrieking witch with a huge head and long skinny legs who flew in and out of her tiny house, which was the only illuminated part of the stage amid the dark forest. After the witch roasted Hänsel in her wood stove, what would prevent her from using her powers to leap into our seats? My mother, my cousins, everyone around me was somehow oblivious to this imminent danger. So I did what any sensible person would do: I screamed.

My poor mortified mother attempted to calm me down, reassuring me that it was “just a show.” But I was not going to let her fool me ‒ until she took me outside.

Decades later, I made peace with this tale when I read Bruno Bettelheim’s psychoanalytic interpretation of “Hänsel and Gretel,” in which he identifies the witch as a symbolic mother substitute whose job it is to teach children independence.

They are grim indeed, those Grimm fairy tales. Chopped-off heels and toes, vicious stepmothers, witches eating children. My students often ask: “What’s wrong with the Germans? They really thought this was somehow good for a child’s young psyche?” Bettelheim’s defense notwithstanding, it is of course important to note that the tales did not originate as children’s literature.

Between 1806 and 1863, the Grimm brothers traveled the German lands in search of folk tales for their collections. Their sources were almost exclusively women. And the women who told them their tales had mainly told them to other women, entertaining each other around the hearth while peeling potatoes or making butter, often by candlelight. Not surprisingly, the women in these tales are quite powerful, playing the roles of both evildoers and heroines.

There is also a lot of blood in these tales. Children aren’t the long-awaited pink and blue arrivals celebrated at modern baby showers. Rather, there are always too many of them, and pregnancy posed a constant threat to a woman’s life. Although the Grimm brothers made changes to the stories for their published editions, many of the tales reflect their own experience with poverty and hunger in their youth.

Much of that realism got lost in Walt Disney’s saccharine, patriarchal, pink princess films from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937) to “Cinderella” (1950) and “Sleeping Beauty” (1959), but spunky heroines and realism have been celebrating a 21st-century comeback, from “Tangled” (2010) to “Frozen” (2013). Disney’s 2014 film version of Stephen Sondheim’s “Into the Woods” is no exception. Sondheim and his collaborator, James Lapine, did, however, introduce an element into their 1986 stage version that had hitherto been largely absent from fairy tales: irony.

Indeed, Sondheim’s musical could be called an anti-fairy tale, given that he tells the familiar stories in Act One only to systematically deconstruct them in Act Two. His Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood and Baker’s Wife are confronted not only with powerful magic and violent giants, but also with the bite of reality that leads them to leave behind their two-dimensional archetypes and traditional happy endings.

Sondheim’s feminist reinterpretations reveal the fascinating duality that the tales have always held: While fantasy villains and happy endings may provide desired escapism, realistic confrontations with danger and death can teach strategies for coping with real-life hardships. We may not all deal with leering wolves and giant beanstalks in our daily lives, but women have always had to be wary of sexual predators (not only since the #metoo movement), and everyone must cope with the loss of a loved one at some point in our lives. Humans all over the world have used songs and tales in an attempt to make sense of experiences that seem senseless.

The Grimm brothers are only the most well-known among a long list of European fairy tale collectors, and the stories they compiled bear striking similarity to stories collected elsewhere in the world, not only due to the universality of the human condition but also thanks to migration, travel and trade. But each tradition also contributes in unique ways to the genre, as can be seen in the wonderful new anthology “The Annotated African-American Folktales” (2017), co-edited by Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Maria Tatar.

German fairy tales begin with “Es war einmal…,” which is similar to “Once upon a time.” But they do not end “happily ever after.” Instead, the typical ending goes, “Und wenn sie nicht gestorben sind, dann leben sie noch heute” [“And if they haven’t died, they are still alive today”]. The Department of Theater Arts including Sondheim’s “Into the Woods” in their current season clearly shows that fairy tales are alive and kicking. I can’t wait to see the show – from a safe distance in the balcony.

Categories: Arts