Leonard Bernstein and the FBI

Courtesy of the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University.

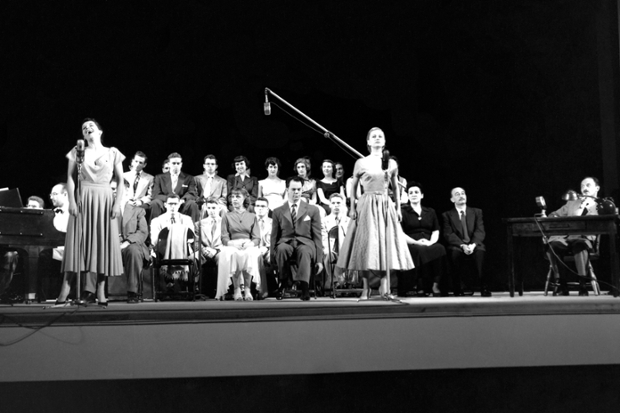

Courtesy of the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University.Rehearsals for the 1952 Brandeis production of "The Threepenny Opera."

Learn more about Leonard Bernstein's FBI file in the exhibition "The Power of Music," on display through Nov. 20 in Spingold Theater Center on the Brandeis campus. It is open Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m., and Thursday from 12 p.m. to 8 p.m, and is free and open to the public. This article originally appeared in the fall issue of State of the Arts.

In the era immediately after the Second World War, the “Red Scare” cast a shadow over much of American public life. The legitimate fear of the Soviet Union was heightened domestically by an inordinate suspicion of the influence of Communists as traitors and spies, and the arts were not exempt from excessive and irrational vigilance.

The Red Scare coincided with the rise of Brandeis University, and even threatened Leonard Bernstein, the most famous musician ever to serve on its faculty. The 1950 edition of Red Channels, the pamphlet that purported to identify Communist Party sympathizers, members and fellow travelers, included Bernstein’s name. In 1951, the FBI placed Bernstein on its Security Index, which meant that ‒ in case of a national emergency ‒ he could be arrested and placed in a detention camp as an enemy sympathizer under the Custodial Detention Program.

The bureau had begun compiling a record on Bernstein in 1939 (the year he graduated from Harvard) and would eventually need well over six hundred pages to trace the extent of his political activities. This swollen dossier suggests the risks that he took (perhaps unwittingly) by signing the numerous progressive petitions that circulated in the cosmopolitan cultural circles he inhabited.

The FBI failed to prove that Bernstein was a Communist but in 1950 did succeed in getting him temporarily blacklisted from the CBS television network. In 1953 the Department of State refused to renew his passport, though Bernstein eventually got his travel documents when expressed remorse for his association with what the government deemed to be Communist fronts.

At Brandeis he was better protected from political surveillance than he would have been at some other universities. As an American Jew, Bernstein did not need to soft-pedal his ethnicity or his values. He taught works by many Jewish composers, both American and European. An undergraduate reporter for the Brandeis Justice noted that when “the mood of the music” made Bernstein joyous, the class followed “the movement and [roared] with laughter.” Yet when he found himself swept by “a sea of torment and despair,” his students wept “passionate tears.”

By the summer of 1953, it was evident that Bernstein’s conducting responsibilities would not allow him to remain on the faculty. He wrote to founding president Abram L. Sachar, who had become a close friend, “it has finally dawned on me that I have been dancing at far too many weddings (please translate).” Nevertheless, he stayed through fall 1954 and served as a Brandeis Fellow for the following two decades, as a trustee from 1976 until 1981, and as a trustee emeritus until his death in 1990.

International fame had long eclipsed whatever threat Bernstein faced in the years of his close association with Brandeis, and his liberalism rather faithfully mirrored the values of postwar American Jewry. He supported civil rights and racial equality, objected to violations of civil liberties, and opposed the military intervention in Vietnam. The zeitgeist affected him deeply, whether in response to the emptiness of suburban success (as portrayed in his opera “Trouble in Tahiti”) or to the shadow of the bomb (as depicted in Symphony No. 2, “The Age of Anxiety”).

Bernstein’s public activism came back to bite him in 1970, when he and his wife, Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein, hosted a party to raise legal defense funds for a group of Black Panthers. Among the guests was author Tom Wolfe, who discredited their efforts with the phrase “radical chic” in a subsequent report in New York magazine. Bernstein’s reputation never quite recovered from the jab, which was even repeated in his 1990 obituary in The New York Times. But Wolfe failed to mention that the FBI trolled through newspapers’ social columns to identify the Bernsteins’ guests, generating files on Americans who had no previous paper trail. A scheme by the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) operation was also designed to neutralize the host himself. Its nastiest tactic was to try to plant gossip about the homosexuality that Bernstein was so carefully concealing. The press was not interested.

His last musical, “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” (1976), with lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, was intended to be a searing Bicentennial critique of slavery and racism. Bernstein’s most overtly political work abjectly failed. But another musical suggests even more forcefully how his artistic gifts and his political courage were entwined. In 1952, Bernstein chose for the centerpiece of the first Brandeis Festival of the Arts “The Threepenny Opera.” This stinging, left-wing masterpiece by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht flopped on Broadway in 1933 and had not been revived. Bernstein championed a brand-new translation and adaptation by his friend Marc Blitzstein, a former Communist and composer of the pro-labor union musical “The Cradle Will Rock” (1937). And Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, even came to campus to resurrect the role that had made her famous in Berlin: the ferocious, vengeful Pirate Jenny. The success of the Brandeis performance, with an audience of about 3,000 people and covered by The New York Times, helped fuel an off-Broadway run later in the decade. Rediscovered, “The Threepenny Opera” ran nearly nine years, topping the Broadway record then held by “Oklahoma!”

Staging this musical at a high-profile event demonstrated audacity in the era of rampant McCarthyism. The national atmosphere, Bernstein wrote to his Brandeis colleague, composer Irving Fine, encouraged “caution” and “fear.” (Of the 221 Republicans elected that year to the House of Representatives, 185 requested to be assigned to the House Un-American Activities Committee.) This fear, Bernstein believed, needed to be punctured. In transplanting a cabaret work from West Germany to a suburban Massachusetts campus, Bernstein asked audiences to consider a savage satire of capitalism as an economic system indistinguishable from criminality, a musical that equated free enterprise with predatory freebooting.

In paying tribute to the work that Weill and Brecht had created as their own nation edged toward the abyss, Bernstein ‒ American-born, American-trained ‒ validated the heritage that several of his faculty colleagues personified. In a decade so timorous that even “A Lincoln Portrait” (1942) was dropped from the program of the 1953 Eisenhower inaugural because the left-leaning Aaron Copland (one of Bernstein’s most important mentors) had composed this manifestly patriotic piece, the university had positioned itself as something of a refuge from the excesses of the domestic Cold War.

Stephen Whitfield is the Max Richter Professor of American Civilization, Emeritus.

Categories: Arts