Students discuss race, responsibility in theater

Faculty use A.R.T. production of 'Porgy and Bess' as experiential learning tool

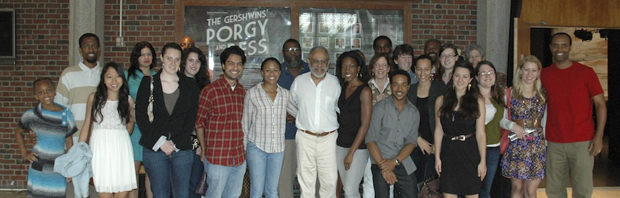

Campus Conversations on Race participants, Brandeis Prof. Ibrahim Sundiata at center, pose with "The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess" cast members Trevon Davis, Lisa Nicole Wilkerson, Nathaniel Stampley, Nikki Renee Daniels and Norm Lewis.

Throughout September, “The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess,” a new adaptation of the opera “Porgy and Bess,” played at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T) in Cambridge; it opens on Broadway in December.

Despite its magnificent score, the original, which premiered 76 years ago at Boston’s Colonial Theater, has been controversial from the start because of its racially stereotyped characters. Equally controversial was the intention of Diane Paulus, artistic director of the A.R.T, to modernize the opera so as to make it accessible to contemporary theater-goers.

Although Paulus’s team included several African-American artists, including Pulitzer Prize-winning dramatist Suzan-Lori Parks and Obie-winning composer Deirdre Murray, some theatrical notables challenged Paulus’ plan to transform an American classic. In the face of urgent questions about representations of race in theater and the responsibility and authority of new generations to transform iconic works of art, a trip to the A.R.T to view this production at first hand seemed like a valuable opportunity for experiential learning.

Luckily we got our tickets during the summer, because every seat of every performance quickly sold out. A group of 65 students and faculty from American Studies, African and Afro-American Studies, Education, Women’s and Gender Studies and Theater visited the A.R.T for the Sunday, Sept. 25, matinee.

After a thrilling performance, with many standing ovations, we stayed for a post-performance discussion with cast members – including Norm Lewis, who played Porgy, and David Alan Grier, who played Sporting Life – members of Students Organized Against Racism, and Brandeis faculty and students. Sponsored by the National Center for Race Amity, the talk was moderated by Jamele Adams, associate dean for student life at Brandeis.

Adams began the talk-back with a rousing rendition of his poem, “BLACK.” One of its most powerful thoughts was that, in the author’s words, “In the theater we are all black.” Adams’ enthusiasm echoed throughout the discussion, as panelists shared their reactions, asked questions, and probed the complicated issues presented in the story and its adaptation.

Almost everyone who spoke mentioned being “overwhelmed” and “blown away” by the production. Many talked about being able to identify with and care about all the characters in the ensemble.

Melissa Howard ‘12, a Brandeis theater major, said that drama remained relevant to her own New York City neighborhood, where just a short time ago a craps game resulted in a murder, as it does in the play, and her grandmother to this day talks about “Dr. Jesus,” a reference to one of the production’s most moving songs.

A student from Emerson who grew up in Tanzania felt the play had global relevance; she could easily relate to the scenes of the fishermen and their boats. Anneke Reich ‘13, a Brandeis American Studies major and frequent theatergoer, said she never witnessed as strong a theatrical community as was presented on stage .

Faith Smith, chair of Brandeis’ African and Afro-American Studies Department, found herself deeply caught up in Bess' story and relationships: “For example, that striking scene of Bess dressed in red, utterly dejected, sitting at the corner of the stage, knowing that she is completely marginalized from this community. When she sees the dead man being caressed by his wife, she understands that this is also a repudiation of her own failure to be so caressed, or to have someone legitimate to caress. What this left me wondering about was Bess’ erotic energy, and the fact that it has or does not have legitimacy only in terms of her willingness to make choices amongst three men."

Ibrahim Sundiata, professor of history and of African and Afro-American studies at Brandeis, noted that the play disrupted stereotypes and tropes about African Americans. Characterizations of a kind of black femme fatale were much in the air when the story was constructed, he commented, as in the 1929 Pulitzer Prize winning "Scarlet Sister Mary," which depicts a conflict between the good church-going community and a wild and wayward wanton, as well as in many other films and other media of the time. The A.R.T production took this old racial trope, humanized it and made the characterization a rounded one.

Students, faculty and audience members praised some of the play’s production values: They appreciated the design, mentioning it was great to see shadows of the cast dancing; they loved the choreography and the vibrant score as well as hearing lines spoken as well as sung – a feature of the opera’s transformation into musical theater.

After the talk-back, Brandeis faculty and students went out and talked some more; we got into a deep discussion about the varied meanings of rape and women’s sexuality, then and now. We plan on taking the conversation back to Brandeis, where we will have a wider discussion of this production and what it means for the cultural representation of race in America.

----------

Joyce Antler is the Samuel B. Lane Professor of American Jewish History and Culture and professor of Women's and Gender Studies, and chairs the American Studies Program.

Categories: Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences