Simon, world-class relief worker, teacher, at milestone

Professor of international development has spent 40 years in field, laboratory and classroom

A good measure of how much success Laurence Simon has had at changing the world may be the number of times the word “founder” pops up in the Brandeis professor of international development’s personal history.

Founder of the graduate Program in Sustainable International Development, a globally renowned crown jewel of the university.

Founder of GrainPro, Inc., a company whose technology has reduced spoilage of grain in developing countries drastically and eliminated the need for chemical fumigation.

Founder of American Jewish World Service, the first international famine and disaster relief agency with a Jewish identity.

That might be the half of it, but the other half is pretty impressive too: Simon has been an antipoverty worker in Sri Lanka, senior adviser on global poverty to the Google Foundation and the author of an expose on U.S.-financed land reform in El Salvador that led to a New York Times investigation and prompted Congressional hearings.

That might be the half of it, but the other half is pretty impressive too: Simon has been an antipoverty worker in Sri Lanka, senior adviser on global poverty to the Google Foundation and the author of an expose on U.S.-financed land reform in El Salvador that led to a New York Times investigation and prompted Congressional hearings.

Small wonder his friends and admirers are throwing a symposium, and a little party, in his honor. The celebration of Simon’s four decades of work in development will run from 2 to 6 p.m. Feb. 7 in Rapaporte Treasure Hall. It’s free and open to the campus community. Reservations are available by email or by calling (781) 736-4197.

Among luminaries participating in the program will be:

- Ruth Messinger, current president of American Jewish World Service and a national leader of the campaign to stop genocide in Darfur

- Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, a leader of programs to enrich Jewish spiritual and cultural life and one of the most influential thinkers in 20th- century American Judaism

- Rabbi Marc Gopin Ph.D. ’93, director of the Center on World Religions, Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University

- Joan Dassin ’69, director of the Ford Foundation International Fellowship Program

- (by video) Larry Brilliant, inaugural executive director of Google.org, who helped define the mission and strategic goals of Google’s philanthropic efforts

In the beginning, Simon’s career followed a path that will seem familiar to many Brandeis undergraduates today. On graduation, he spent three years working for a tutoring program for inner-city youth, and a year teaching elementary school in the Bronx. A job at Fordham University led to work with development agencies, including Oxfam America, in Latin America and Africa.

A turning point came in 1982 on a flight from Lusaka, Zambia, to Rome, en route to his first visit to Israel. Simon was seated next to a leader of the African National Congress, which was then engaged in a deadly conflict with the apartheid government of South Africa.

“The man was surprised, perhaps even disappointed that I – a longtime supporter of the ANC struggle – would be going to Israel,” Simon recalls. “This troubled me, for his reasons were not at all anti-Semitic but based on Israel’s military assistance to the apartheid government.”

As he walked the streets of Jerusalem, Simon brooded on this, and on the widespread feeling he encountered among the Africans with whom he was working, that “the Jews are not on our side,” despite what Simon knew were Jews’ disproportionate presence in aid, development and human rights work.

He decided “Jews needed to have a recognizable identity in developing countries. I felt it was important that Jews be seen as they are – extraordinarily generous and humane and capable of bringing solutions to some of the problems of Africa. I also felt it would open the door for American Jews to Third World conditions and Third World oppression.”

This was the beginning of American Jewish World Service. Including “American” and the “Jewish” were obvious. “World Service” came directly from the BBC, of whose shortwave programs he was an avid consumer.

When incorporated in Massachusetts the organization listed Simon’s home address in Cambridge as its headquarters, but it soon succeeded bigtime, drawing support from a broad swath of religious and secular leaders.

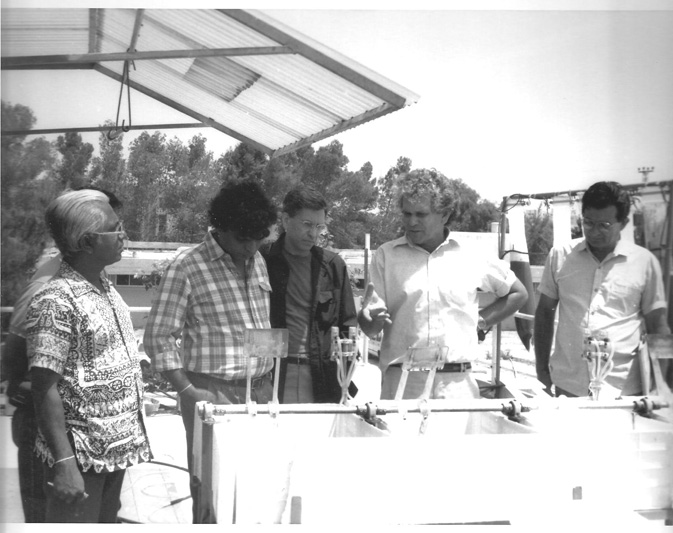

In his new role – a Jew working at tikkun olum, rather than as a secular professional – Simon went hunting for innovations in Israel. There he found brilliant solutions to public health and agricultural problems, but they were too high tech or skill intensive to be adaptable readily to developing countries – until he got to the Agricultural Research Organization and had a literally world-changing encounter with two scientists who had developed a new method to store durable grains.

“They demonstrated they could store durable grain with no fumigation, no chemicals, no treatment at all, for many years with zero percent loss – it was breath-taking, astounding,” Simon says, and the only major problem was that the scientists were working on a much larger scale than was practical for Third World or international relief uses.

He got a $300,000 grant to permit the scientists to accompany him on trips to Africa and Asia to look at practical problems of grain storage in countries where food was desperately precious but tremendous amounts of grain were routinely lost because of poor storage conditions. The scientists adapted their technology to local needs, United Nations endorsement was obtained, and production began at Kibbutz HaOgen.

When Simon left AJWS, five years after its founding, the grain-storage technology was ready to take off. He had a friend at the US Agency for International Development who wanted the technology to help the Kurds in northeastern Iraq. As always, there was a “but…” The key bureaucrat Simon had to deal with at US AID said “Wait, you’re an NGO. We give to NGOs; we don’t buy things from NGOs.”

So Simon created GrainPro Inc. to sell the technology to the government. Then it was back to fieldwork.

He was in Sri Lanka working for the United Nations Development Program when a fax came from Irv Epstein, then dean of arts and sciences at Brandeis, asking whether Simon could take over the course load of Professor of Politics Ruth Morgenthau, who was going on medical leave.

“It coincided with my schedule and I said ‘Yeah, great!’” Simon recalls. He already had in mind the idea of a program in sustainable international development, and during his time filling in he convinced Morgenthau, then Epstein and Provost Jehuda Reinharz.

“Irv said he loved the idea but didn’t know if there was a market for it,” Simon said. “He gave me $25,000 walking around money to see what I could do about bringing in the first class.”

There were six students that first year. The second year there were about 12, nine of whom were Fulbright scholars. That convinced the administration, and the program ramped up from there. After its inception in the Politics Department, the program moved to the Heller School of Social Policy and Management; its graduates now number more than 1,300.

“There have been many wonderful moments,” Simon says, when asked what have been the most gratifying experiences of his career. “The grain storage work is probably really a lasting contribution. But so is SID. If the real challenge in development is building local capacity for solving problems, this is a contribution that will go on long after me. Those are the two things I feel best about.”