Small steps and giant leaps

For 30 years, Brandeis University has helped astronauts live and work in space

Photo/NASA

Photo/NASAOn July 20, 1969, Janna Kaplan, then a high school junior, sat with her family in a small, seaside resort outside Leningrad in the Soviet Union, her eyes glued to the black and white television. Around her, angry murmurs decried the American victory over the Soviets in the Space Race, but Kaplan was oblivious.

Watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon was surreal, spectacular — and it forever changed her life.

“As I was watching, and listening to Armstrong’s words, I knew I would spend my life involved in space research,” Kaplan, a senior research associate at Brandeis University and an expert on human space flight, recalls. “Even though I was a Jewish girl in Russia, I knew I would somehow be a part of this.”

|

|

|

Memories of Apollo 11 "I was 13 years old and living in Curaçao. After the landing, I went out to look at the moon that night and it looked different. It felt like family, like it was part of us. Before, when I looked at the moon with the naked eye, it was cold and remote but knowing that we were up there, it felt different." — Ben Gomes-Casseres, ’76 P'15, professor of international business "I was dating a young man named Jack who was studying lunar geology. He gazed at the moon much more than he ever gazed at me, so in an attempt to attract his attention, I learned the names of the moon’s craters, extinct volcanoes and dry lake beds. A few days before the lunar landing, I found out that craters on the dark side of the moon had been named for two famous archaeologists, Sir Arthur Evans and Heinrich Schliemann. My desire to impress Jack waned significantly and my passions became squarely focused on the ancient peoples who had also stared at the moon for so many generations to discover her secrets. On July 20, 1969, some of those secrets were about to be revealed. It was an opportunity to understand the moon over time and space, no longer just to promote an awkward romance. Moon craters Evans and Schliemann and the moon landing itself brought me back to my senses." — Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, chair of the Department of Classical Studies "That was the summer after 9th grade for me, race riots, antiwar demonstrations and civil unrest were everyday occurrences. Martin Luther King Jr.'s and Robert F. Kennedy's assassinations were still fresh on our minds. My whole family watched the live broadcast on an old black and white television in our basement in Parma, Ohio. The pictures were blurry, and Neil Armstrong was hard to understand, but for at least a few minutes, all of the differences that divided the planet seemed a little less important. I remember looking up at the first full moon after the landing and thinking "Hey, you aren't as far away as we thought." — Thomas Pochapsky, professor of chemistry |

| |

On the other side of the world, Jim Lackner, the Meshulam and Judith Riklis Professor of Physiology, watched the lunar landing with fellow MIT graduate students — and his future wife — in Cambridge, Mass. He was awed by the feat but not changed as Kaplan was. That happened about 10 years later, when he experienced zero G for the first time in parabolic flight.

His first few minutes of weightlessness were disorientating, but gradually, he noticed his body adapting. It was fascinating.

“I got off that plane and had the beginnings of my first paper on human adaptation in zero G,” Lackner recalls. “I found an area of research I loved and I knew I was never going to give it up.”

Paul DiZio, PhD’86, associate professor of psychology and chair of the Psychology Department, isn’t as romantic about space exploration as his colleagues are. His lasting memory of humankind’s first lunar landing is that it was one of the rare times no one argued over which TV show to watch. However, DiZio is fascinated by what doesn’t happen in space — gravity.

“To me, the moon landing was doing what we knew how to do and doing it to perfection,” DiZio says. “That doesn’t interest me. I’m much more interested in understanding the thing we don’t know that’s right in front of us, like gravity.”

For more than 30 years, these three scientists have led research at Brandeis University’s Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Lab, located in the basement of the Rabb Graduate Center. Together, they have advanced our understanding of how humans can live and work in space, among many other achievements.

The lab, founded by Lackner and co-directed by DiZio, is named in honor of Dr. Ashton Graybiel, a NASA flight surgeon and pioneering researcher in the effects of weightlessness on the human body. Graybiel was Lackner’s longtime collaborator and father-in-law.

The lab opened in 1982, with support from NASA’s division of life sciences. Over the years, the Graybiel Lab has hosted several NASA astronauts, including John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin and Shuttle astronauts Bill Thornton and Gordon Fullerton.

The lab’s seminal work on motion sickness in zero gravity has helped astronauts live and work on the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station, and its experiments on the effects of artificial gravity on the human body are paving the way for future, long-term voyages in space.

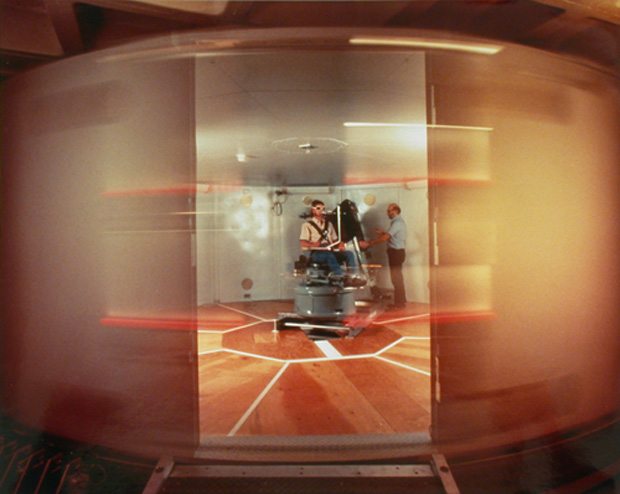

The lab’s research has also impacted life on Earth. Experiments in the famous rotating room, the only one in the U.S., have shed light on how the brain activates muscles and adapts to changing environments. This research has impacted our understanding of autism, movement control, and helped develop strategies for people suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

|

|

The rotating room, Photo/National Geographic |

Today, the lab no longer works directly with NASA but trains future commercial astronauts in the private sector. Private launch providers are now rapidly developing the spaceflight industry with an eye for space tourism, scientific and industrial research, and long duration spaceflight to the Moon and to Mars. The Graybiel Lab’s astronaut training outshoot, SIRIUS Astronaut Training, trains astronauts in how to control space motion sickness, movement in altered gravity, spatial orientation and disorientation and sensory illusions.

NASA had changed since 1969, Lackner says. It is more bureaucratic and less willing to take risks.

"NASA is searching for ways to inspire a new generation of young people in human space flight and interplanetary travel and exploration," Lackner says.

Commercial space travel and a potential space race with China may reinvigorate the celestial wanderlust that captured so many people around the world that Sunday in 1969, Lackner and Kaplan say. But, until then, the researchers in Rabb’s basement will continue looking skyward.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology