Y.L.: The COVID, we cannot control it

A married woman with two children, Y.L. immigrated to the U.S. from China thirteen years ago. At age 34, she became a housekeeping supervisor at a large hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, but since the coronavirus epidemic shuttered the hospitality industry, Y.L. has been unemployed.

Photo Credit: Sarah Putnam (all photos)

Y.L. was born the middle child to small farmers in a village in Guangdong Province, China. While she was young, Y.L.’s father and mother divorced. A person like her, with only a ninth-grade education, could not get a good job in China. That meant that when her father decided to migrate to the U.S., she saw it as a great opportunity and joined him. Her mother and married older sister stayed in China.

She and her father traveled with a group of other immigrants to Boston where they stayed with her father’s younger sister. Although 20 at the time, Y.L. attended high school for a while, but found it too difficult to fit in as an older student who was not fluent in English. And she needed to earn a living. Y.L.’s auntie found her a job cleaning houses and charged her $200 per month for sleeping in a bed in a room she shared with two other relatives. Y.L. got a job as a cashier, and then went into housekeeping at a hotel. The work was grueling but stable. After several years in this country she gained enough experience in hotel work to enable her to land a job at a big hotel in downtown Boston where the pay was higher.

She and her father traveled with a group of other immigrants to Boston where they stayed with her father’s younger sister. Although 20 at the time, Y.L. attended high school for a while, but found it too difficult to fit in as an older student who was not fluent in English. And she needed to earn a living. Y.L.’s auntie found her a job cleaning houses and charged her $200 per month for sleeping in a bed in a room she shared with two other relatives. Y.L. got a job as a cashier, and then went into housekeeping at a hotel. The work was grueling but stable. After several years in this country she gained enough experience in hotel work to enable her to land a job at a big hotel in downtown Boston where the pay was higher.

Y.L. married her sweetheart from her home village. When she became pregnant, her auntie kicked her out of the house because she thought that a woman giving birth to a child in her home would bring bad luck. When her son was born, Y.L. took him to China to have her mother care for him until he turned two, so she could continue to work.

For her husband, the immigration experience had not brought the upward mobility that it had for Y.L. Because he had gone to college in China, the first in his family to do so, he found a plumb job as a middle school P.E. teacher and coach in China. Although his salary was not high, it was supplemented with benefits from the government. In China, this kind of job was called an “iron rice bowl” because of its guaranteed job security, steady income, and substantial benefits. But in the U.S., the only work he could find was as a waiter in a restaurant.

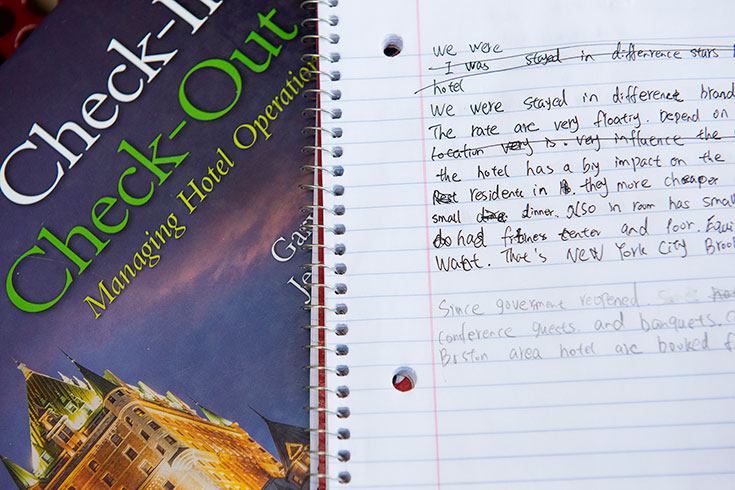

After five years, Y.L. was promoted to housekeeping supervisor, overseeing other cleaners, a majority of whom were Chinese women. As her responsibilities increased—making sure the rooms met the hotel standard of cleanliness and workers were doing their jobs—her stress level also increased, prompting her to lose ten pounds. Though her job was challenging, Y.L. was proud of her position and sees a future for herself in the hotel business. In addition to taking English as a second language classes in Chinatown, she has started enrolling in hospitality management training classes at Bunker Hill Community College.

When COVID-19 hit Boston in March 2020, Y.L. was laid off and has been unemployed ever since. She is hoping that she will be hired back to her old job, but the hotel is still closed. Given how hard the hospitality industry has been hit, the future is unclear. Y.L. gets unemployment insurance, which has made a huge difference to her family’s financial solvency. The family lives in a rent-subsidized apartment and they are enrolled in Mass Health. Even with the hardship of the pandemic, Y.L. thinks the government has helped her a lot, especially the federally issued stimulus checks and the subsidy for school lunch.

Her husband, who works in a restaurant, was also laid off in March 2020. When restaurants reopened in Massachusetts in September 2020, he was called back. As an essential worker, his situation poses other kinds of uncertainty because of his exposure to the public while at work. As Y.L. notes, every day he “faces a lot of people,” endangering himself and in turn, their family. The children, now 11 and 7, are attending school remotely from home. Y.L.’s father lives with them, which provides him with a safe place to live and enables him to help with the children. They are a household of five people, only one of whom is bringing in a salary.

Her husband, who works in a restaurant, was also laid off in March 2020. When restaurants reopened in Massachusetts in September 2020, he was called back. As an essential worker, his situation poses other kinds of uncertainty because of his exposure to the public while at work. As Y.L. notes, every day he “faces a lot of people,” endangering himself and in turn, their family. The children, now 11 and 7, are attending school remotely from home. Y.L.’s father lives with them, which provides him with a safe place to live and enables him to help with the children. They are a household of five people, only one of whom is bringing in a salary.

At this juncture, Y.L. doesn’t know what the future holds. She has considered applying for a job at another hotel that has reopened and where her former boss now works. But, she reasons, she would lose her thirteen years of seniority and have to start all over again. She is hoping her hotel will reopen and she can go back to her former job, but she doesn’t know when or if it will. Her other concern about starting work at another hotel is that she would be working the night shift. Because her husband works the swing shift, he rarely arrives home before midnight. She feels the weight of responsibility for childcare and she would have to leave for work before her husband got home. That doesn’t feel right for them as a family.

Her husband is considering changing jobs. Through Chinese and Vietnamese community networks, he is considering the possibility of learning a new skill: installing flooring. This construction job would make his hours more regular, and he would not have to work evenings and weekends, making it easier for him to help with childcare. Eventually, it could lead to him setting up his own business and having more work autonomy.

Y.L. says, “It feels like a little bit hard for right now, because we don't know what the future will hold. The COVID, we cannot control it.” Between the virus, employment uncertainty, and growing anti-Asian sentiment, the world feels more dangerous to her and her children.

Y.L. says, “It feels like a little bit hard for right now, because we don't know what the future will hold. The COVID, we cannot control it.” Between the virus, employment uncertainty, and growing anti-Asian sentiment, the world feels more dangerous to her and her children.

Y.L. doesn’t belong to a church or a neighborhood organization, but recently she has been taking a customer service class at an NGO in Chinatown where immigrants gather and learn job skills. On-line classes at Bunker Hill Community College have made it possible for her to take English classes and pursue a hospitality management degree.

Y.L. feels a strong sense of economic responsibility for her family here and for her mother back in China, to whom she regularly sends remittances. However difficult, from her perspective, immigration has improved her life and offered more opportunities for her and her family.