Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" Manuscript and Correspondence

September 29, 2009

Description by Stephen J. Whitfield, Max Richter Professor of American Civilization, Department of American Studies

A year after his first novel appeared, Joseph Heller got a query from his Finnish translator, who needed to solve the following riddle: "Would you please explain me one thing: What means Catch-22? I didn't find it in any vocabulary."[1] By 1974 the translator could have consulted Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language (2nd College Edition), which classifies "catch-22" as a common noun. Yet only an uncommon author could coin so indispensable a term, and indeed much about his book is unusual. It was the first novel Heller ever tried writing, and though the first chapter had been published in a journal in 1955, six more years were needed to finish the book. Had he known how long it would take, Heller later remarked, he might not have started writing it.[2]

A year after his first novel appeared, Joseph Heller got a query from his Finnish translator, who needed to solve the following riddle: "Would you please explain me one thing: What means Catch-22? I didn't find it in any vocabulary."[1] By 1974 the translator could have consulted Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language (2nd College Edition), which classifies "catch-22" as a common noun. Yet only an uncommon author could coin so indispensable a term, and indeed much about his book is unusual. It was the first novel Heller ever tried writing, and though the first chapter had been published in a journal in 1955, six more years were needed to finish the book. Had he known how long it would take, Heller later remarked, he might not have started writing it.[2]

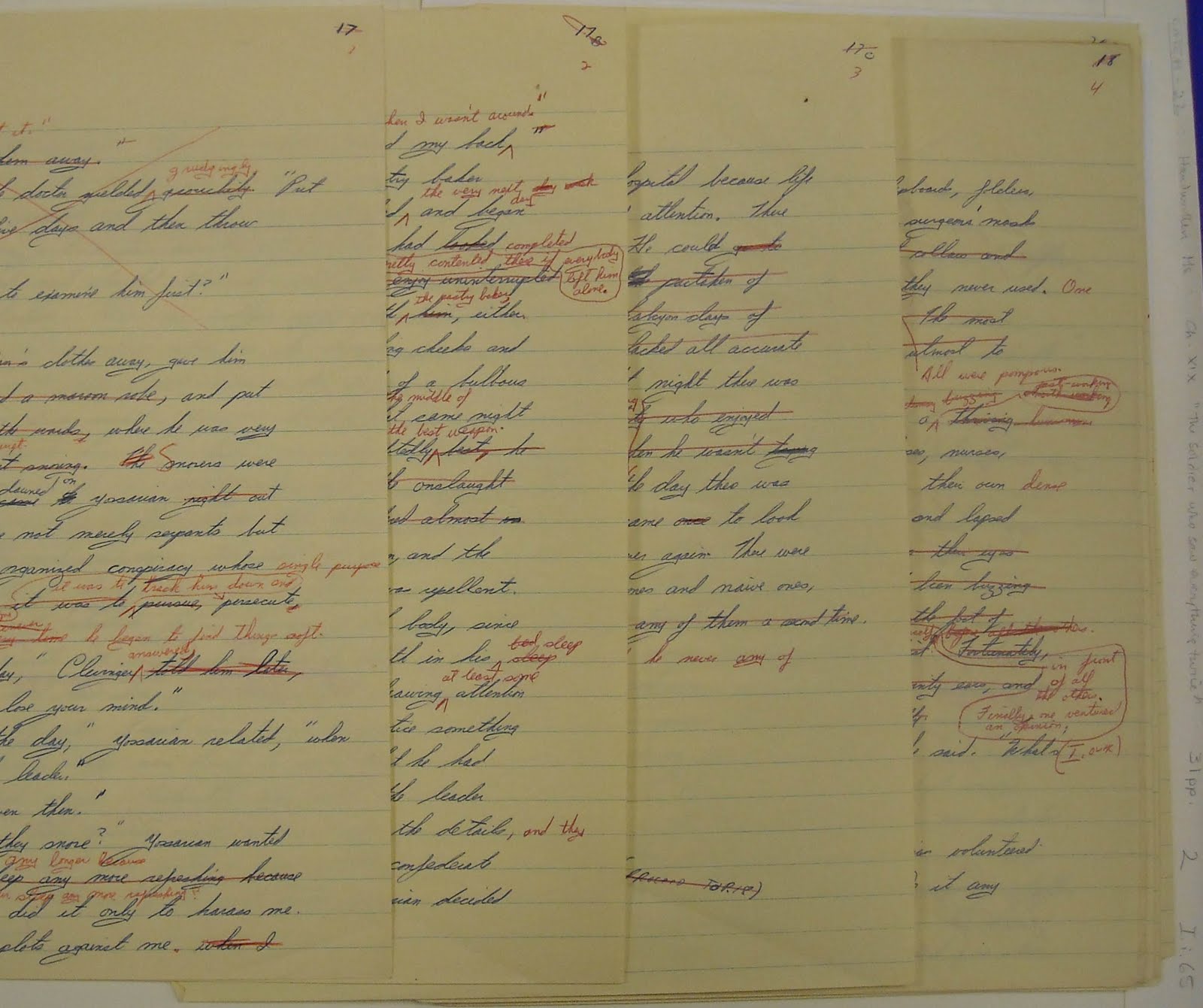

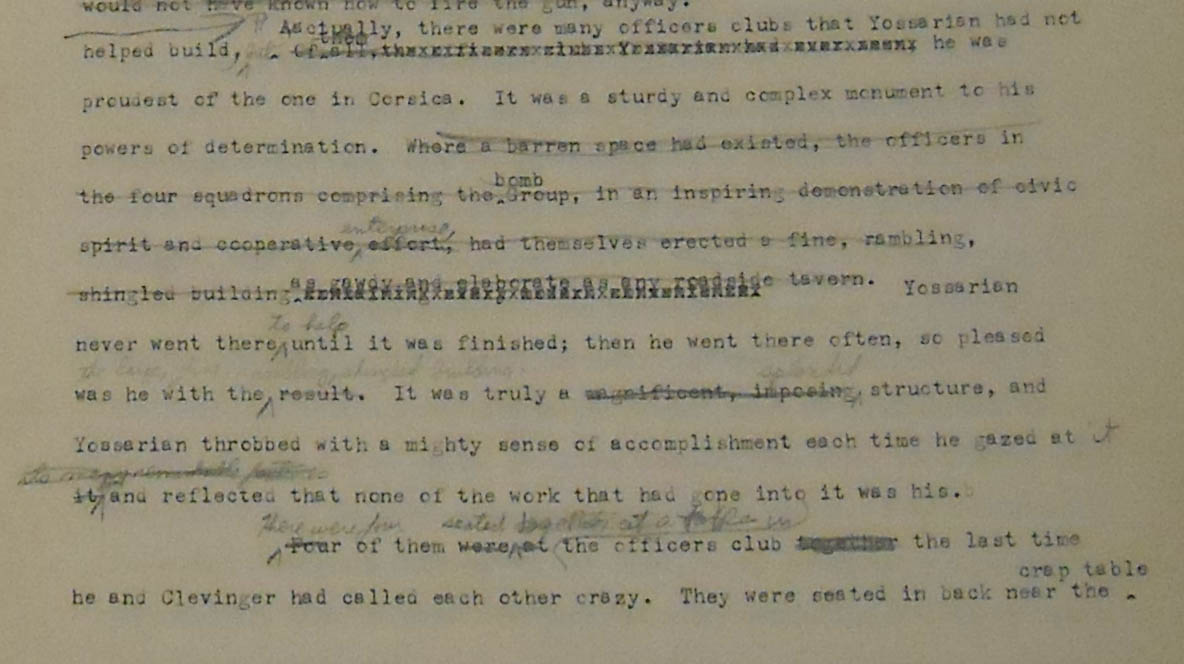

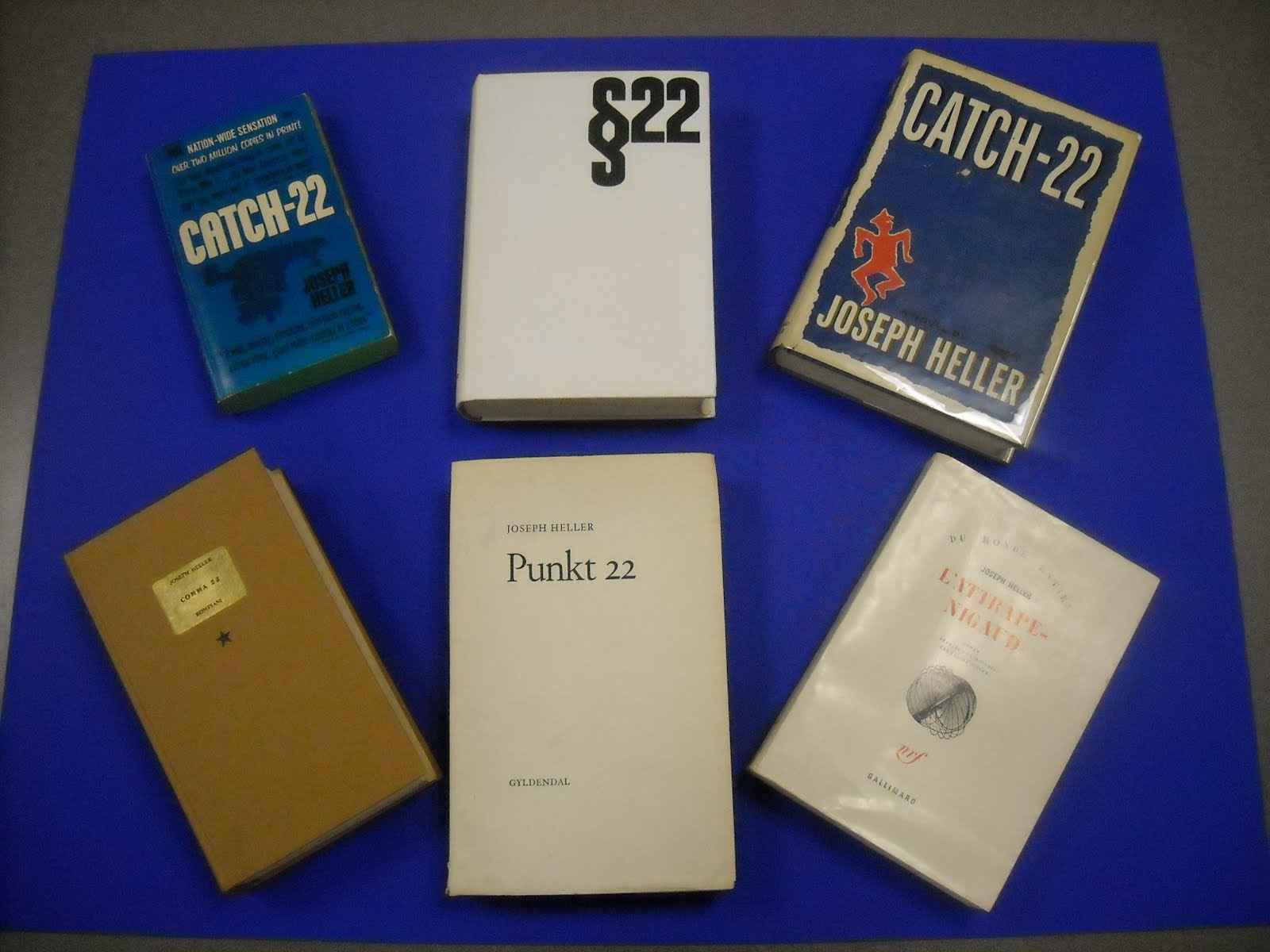

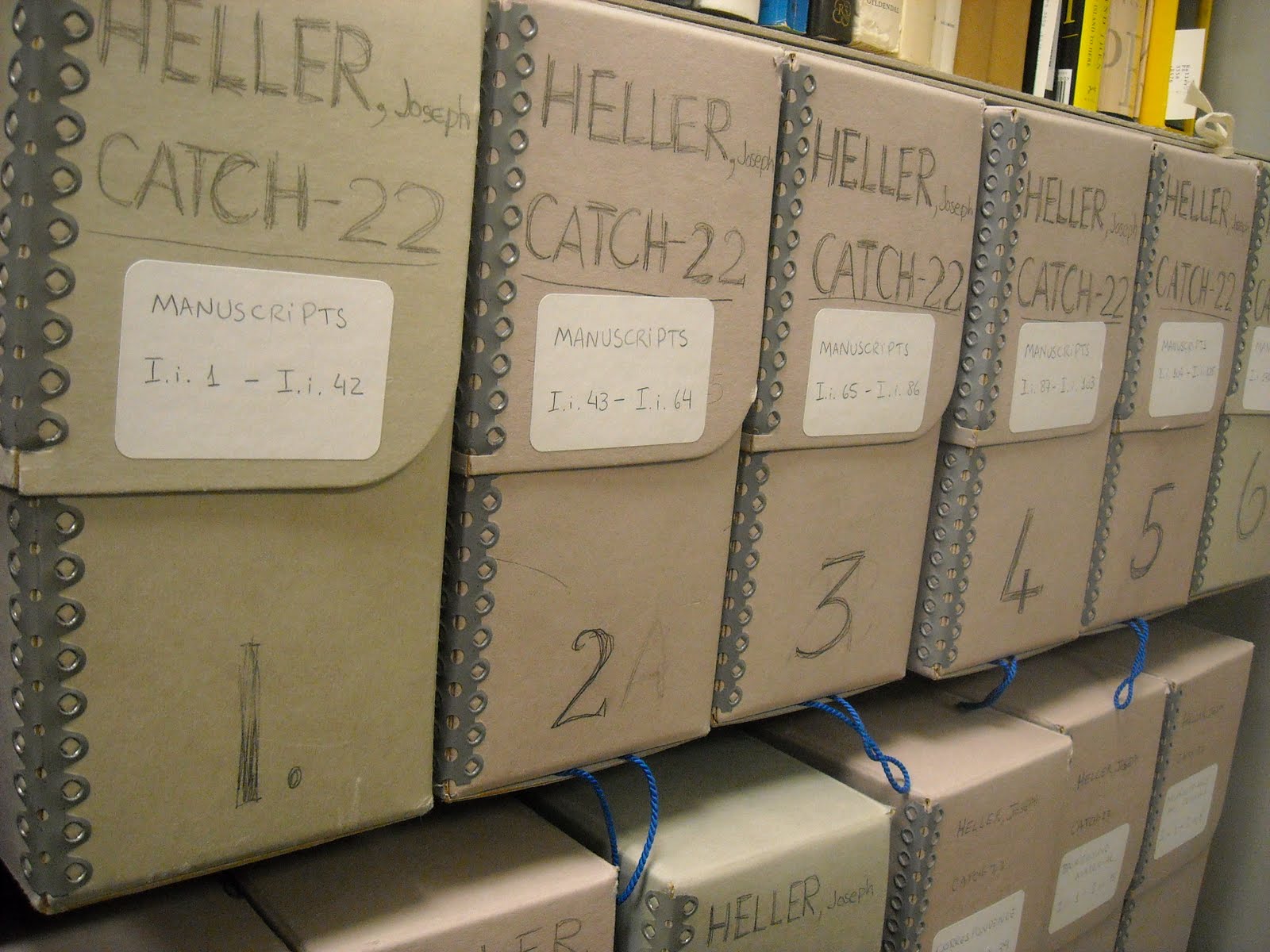

"Catch-22" never came close to making the New York Times bestseller list, and at first lived precariously as a word-of-mouth "cult" novel. But as the military intervention in Vietnam gained momentum, as that disaster helped to spawn a counterculture, the novel became a phenomenal popular success, guaranteeing that Heller would never need to dig for quarters out of car seats. A decade later, "Catch-22" was more popular than immediately after publication, and dwarfed the later, growing success of other serious novels that had appeared around the same time — like Ken Kesey's "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1962) and Kurt Vonnegut's "Cat's Cradle" (1963). In fact, "Catch-22" has become one of the most popular novels ever written, with perhaps 12 million copies sold in hardcover and paperback.[3] Such phenomenal success makes Heller's manuscripts and correspondence archived at Brandeis University of unusual value and interest. The original manuscript of "Catch-22," written on yellow legal pads, is frequently used by students and scholars interested in its myriad corrections and editorial changes.

"Catch-22" never came close to making the New York Times bestseller list, and at first lived precariously as a word-of-mouth "cult" novel. But as the military intervention in Vietnam gained momentum, as that disaster helped to spawn a counterculture, the novel became a phenomenal popular success, guaranteeing that Heller would never need to dig for quarters out of car seats. A decade later, "Catch-22" was more popular than immediately after publication, and dwarfed the later, growing success of other serious novels that had appeared around the same time — like Ken Kesey's "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1962) and Kurt Vonnegut's "Cat's Cradle" (1963). In fact, "Catch-22" has become one of the most popular novels ever written, with perhaps 12 million copies sold in hardcover and paperback.[3] Such phenomenal success makes Heller's manuscripts and correspondence archived at Brandeis University of unusual value and interest. The original manuscript of "Catch-22," written on yellow legal pads, is frequently used by students and scholars interested in its myriad corrections and editorial changes.

"Catch-22" is populated with "characters whose antics were far loonier than anything ever seen before in war fiction — or, for that matter, in any fiction," literary scholar John Aldridge observed. From Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos down to Norman Mailer, war novels were supposed to be written in the vein of spare, austere "documentary realism."[4] But what was Heller getting at? Was he joking about the most horrifying of all themes, turning on laughing gas to get rid of the stench of death? The characters he had invented were mostly cartoons, and some were grotesque. The situations were outlandish. Lip-readers might well have inferred that the men who defeated the Axis in the most awful of wars were uncomprehending buffoons whose commanding officers were either mad or moronic. Infantry platoons were often celebrated as rainbow coalitions, yet why would the protagonist of Heller's novel be an Assyrian and the chaplain an Anabaptist? No wonder then that Aldridge claimed that critics and other readers had to learn to become more sophisticated, to fathom the striking originality of Heller's novel.

"Catch-22" is populated with "characters whose antics were far loonier than anything ever seen before in war fiction — or, for that matter, in any fiction," literary scholar John Aldridge observed. From Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos down to Norman Mailer, war novels were supposed to be written in the vein of spare, austere "documentary realism."[4] But what was Heller getting at? Was he joking about the most horrifying of all themes, turning on laughing gas to get rid of the stench of death? The characters he had invented were mostly cartoons, and some were grotesque. The situations were outlandish. Lip-readers might well have inferred that the men who defeated the Axis in the most awful of wars were uncomprehending buffoons whose commanding officers were either mad or moronic. Infantry platoons were often celebrated as rainbow coalitions, yet why would the protagonist of Heller's novel be an Assyrian and the chaplain an Anabaptist? No wonder then that Aldridge claimed that critics and other readers had to learn to become more sophisticated, to fathom the striking originality of Heller's novel.

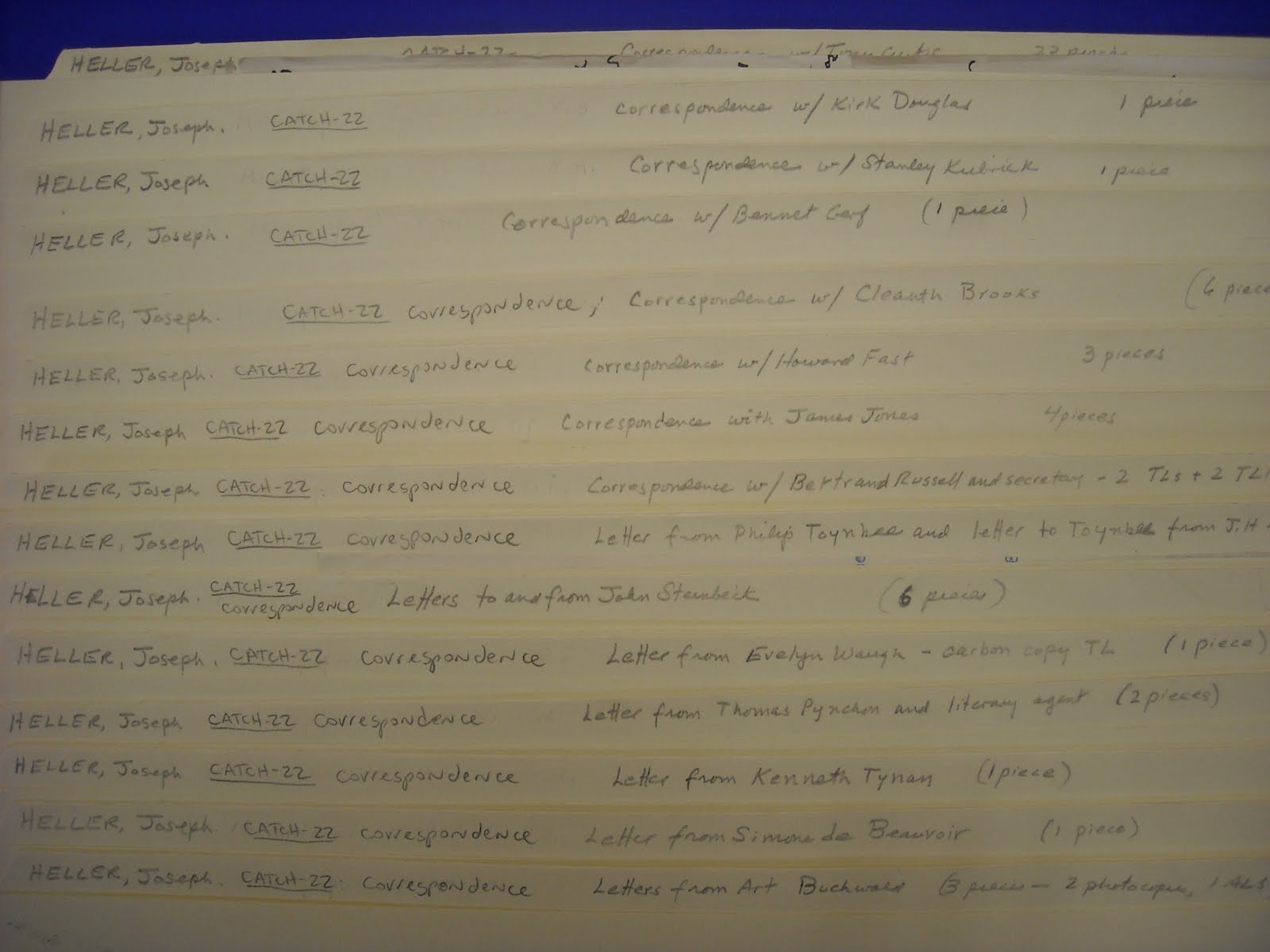

Yet private correspondence with Heller, available in Brandeis Special Collections, cannot be perfectly squared with Aldridge's argument. Many of Heller's fellow writers were quick to understand and to welcome what he accomplished. "From Here to Eternity" (1951), for example, barely resembled "Catch-22." Yet James Jones praised it as "a delightful and disturbing book. Its weird comedy is marvelous, and underneath this on an entirely different level, its pathos for the tragic situation of the men is equally fine." Two years after it was published, Dos Passos himself, then a conservative and a Republican, also spoke highly of so subversive a text. The author of "The Young Lions" (1948), Irwin Shaw, also raved about Heller's new novel. The legacy of John Steinbeck includes "The Moon is Down" (1942), set in World War II; no American novelist did more for social realism. Yet the Nobel laureate realized that "Catch-22" merited re-reading, that "a good book" the first time around proved to be "loaded with things that must be come at slowly… My wife says she knows when I am reading 'Catch-22' because she can hear me laughing in the next room and it is a different kind of laugh."[5]

Yet private correspondence with Heller, available in Brandeis Special Collections, cannot be perfectly squared with Aldridge's argument. Many of Heller's fellow writers were quick to understand and to welcome what he accomplished. "From Here to Eternity" (1951), for example, barely resembled "Catch-22." Yet James Jones praised it as "a delightful and disturbing book. Its weird comedy is marvelous, and underneath this on an entirely different level, its pathos for the tragic situation of the men is equally fine." Two years after it was published, Dos Passos himself, then a conservative and a Republican, also spoke highly of so subversive a text. The author of "The Young Lions" (1948), Irwin Shaw, also raved about Heller's new novel. The legacy of John Steinbeck includes "The Moon is Down" (1942), set in World War II; no American novelist did more for social realism. Yet the Nobel laureate realized that "Catch-22" merited re-reading, that "a good book" the first time around proved to be "loaded with things that must be come at slowly… My wife says she knows when I am reading 'Catch-22' because she can hear me laughing in the next room and it is a different kind of laugh."[5]

Old-fashioned sorts of writers were thus quick to pick up the radically disorienting portrayal that this first novel was presenting. This essay would be incomplete, however, if it did not mention the impact that "Catch-22" exerted on a 23-year-old unknown whom Heller's agent claimed was "the only other genius" she had the privilege of representing. From the future author of another novel set in World War II, "Gravity’s Rainbow" (1973), Candida Donadio received the following letter: "You thought I'd LIKE it. Jesus. I love it. I won't tell you how much or why," Thomas Pynchon wrote, "because I always sound phony whenever I start running off at the mouth like a literary critic. But it's close to the finest novel I've ever read… Who is this guy Heller… [?]"[6]

Old-fashioned sorts of writers were thus quick to pick up the radically disorienting portrayal that this first novel was presenting. This essay would be incomplete, however, if it did not mention the impact that "Catch-22" exerted on a 23-year-old unknown whom Heller's agent claimed was "the only other genius" she had the privilege of representing. From the future author of another novel set in World War II, "Gravity’s Rainbow" (1973), Candida Donadio received the following letter: "You thought I'd LIKE it. Jesus. I love it. I won't tell you how much or why," Thomas Pynchon wrote, "because I always sound phony whenever I start running off at the mouth like a literary critic. But it's close to the finest novel I've ever read… Who is this guy Heller… [?]"[6]

This guy also received unsolicited fan mail from Nelson Algren ("the laughter is hard-won… Thanks for writing 'Catch-22' ”), from novelist and political activist Jeremy Larner '58 ("I read every word of 'Catch-22' with great delight and ended up scared and moved and happy"), from the British drama critic Kenneth Tynan ("a bloody masterpiece"), and from Stephen Ambrose, who would become a prolific military historian: "For 16 years, I have been waiting for the great anti-war book which I knew World War II must produce. I rather doubted, however, that it would come out of America; I would have guessed Germany. I am happy to have been wrong." In some ways, Ambrose added, "Catch-22" is superior even to "All Quiet on the Western Front" (1929).[7] The enthusiastic appreciation of other writers Heller earned at the outset.

This guy also received unsolicited fan mail from Nelson Algren ("the laughter is hard-won… Thanks for writing 'Catch-22' ”), from novelist and political activist Jeremy Larner '58 ("I read every word of 'Catch-22' with great delight and ended up scared and moved and happy"), from the British drama critic Kenneth Tynan ("a bloody masterpiece"), and from Stephen Ambrose, who would become a prolific military historian: "For 16 years, I have been waiting for the great anti-war book which I knew World War II must produce. I rather doubted, however, that it would come out of America; I would have guessed Germany. I am happy to have been wrong." In some ways, Ambrose added, "Catch-22" is superior even to "All Quiet on the Western Front" (1929).[7] The enthusiastic appreciation of other writers Heller earned at the outset.

Such responses are even more striking when the structure of his novel is considered. If reduced to plot summarization, "Catch-22" is rather thin. It recounts the conflict between a bombardier and a superior officer over how many missions should be flown. Rearranged in chronological order, "Catch-22" seems rather uneventful: three missions to Avignon, to Bologna and to Ferrara have all occurred before the time of the first chapter, and M&M Enterprises has been formed. As characterizations, Heller's three dozen servicemen do not exactly bulge with the three-dimensionality that is often credited to the finest fiction. Most — but not all — are caricatures, and even what protagonist John Yossarian looks like is sketchy. For all of its scale, this novel lacks lyrical descriptions, or precise evocations of the natural world or metaphysical depth.

Yet by this book we, as well as our posterity are likely to know Heller the way we also know Cervantes and Swift and Voltaire — which is by one book, and only one book. The cauterizing humor and pungent politics that Heller stirred together have been enduring enough, after nearly half a century, to catch the reader’s attention; and that’s some catch, that "Catch-22."

More Information

- Finding aid to Joseph Heller Collection, 1945-69

- BrandeisNOW video on Stephen Whitfield and the "Catch-22" manuscript

- WGBH "Greater Boston with Emily Rooney" segment on Stephen Whitfield and the "Catch-22" manuscript

Notes

- Markku Lahtela to Joseph Heller, April 12, 1962, folder I.ii.9, Joseph Heller Collection, Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections, Brandeis University; Sam Merrill, "Playboy Interview: Joseph Heller," reprinted in Conversations with Joseph Heller, ed. Adam J. Sorkin (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993), 173.

- George Plimpton, "Joseph Heller," and Chet Flippo, "Checking in with Joseph Heller," in Conversations, 115, 234.

- George Mandel, "Literary Conversation with Joseph Heller," and Seth Kupferberg and Greg Lawless, "Joseph Heller: 13 Years from 'Catch-22' to 'Something Happened' ” (1974), in Conversations, 68, 122; Sarah Lyall, "For Joseph Heller, It's Finally Catch-23," International Herald Tribune, Feb. 17, 1994, 20.

- John W. Aldridge, "The Loony Horror of It All — 'Catch-22' Turns 25," New York Times Book Review, Oct. 26, 1986, 3, and " 'Catch-22' Twenty-Five Years Later," Michigan Quarterly Review, 26 (Spring 1987), 381.

- James Jones to Nina Bourne, Oct. 9, 1961, folder I.ii.20; Georges Cuibus to Joseph Heller, July 13, 1964, folder I.ii.10; Art Buchwald to Max Schuster, September 1961, folder I.ii.12; John Steinbeck to Joseph Heller, May 7, 1963, folder I.ii.17, Joseph Heller Collection.

- Thomas Pynchon to Candida Donadio, Nov. 2, 1961, folder I.ii.15, Joseph Heller Collection.

- Nelson Algren to Joseph Heller, Dec. 7 [1961], folder I.ii.11; Jeremy Larner to Heller, March 28, 1962, folder I.ii.29; Kenneth Tynan to Heller, July 26, 1962, folder I.ii.14; Stephen E. Ambrose to Heller, Jan. 23, 1962, folder I.ii.3, Joseph Heller Collection.

Comment

Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Sept. 1, 2013

"I always laughed when I read this book. Yossa became my favourite. In fact, every character of this book is memorable. Yossa, Doc, Milo,Major Major, Dunbar, Joe… everyone, The books is all about paradoxes and opposing terms. Awesome experience I had."