French Revolution Pamphlets, 1761-1807

November 29, 2011

Description by Drew Flanagan, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

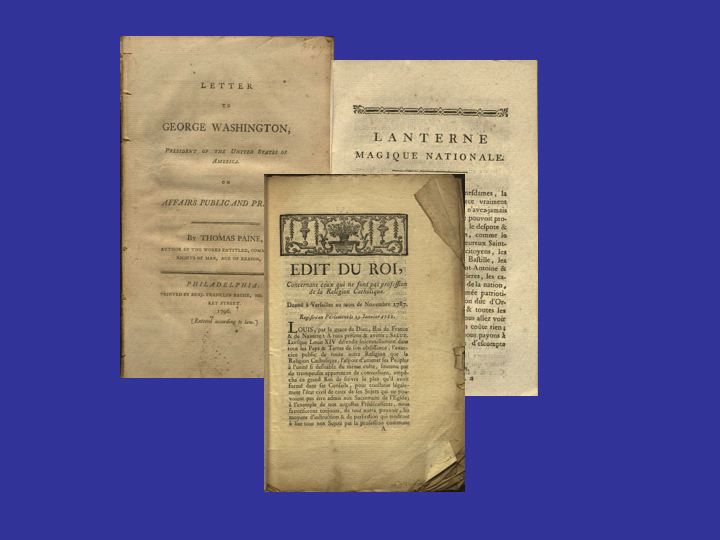

The French Revolution Pamphlets collection at Brandeis University's Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department consists of 94 documents (three linear feet) published during the period of the French revolution and during the years immediately preceding and following that revolution (1761-1807).

The French Revolution Pamphlets collection at Brandeis University's Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department consists of 94 documents (three linear feet) published during the period of the French revolution and during the years immediately preceding and following that revolution (1761-1807).

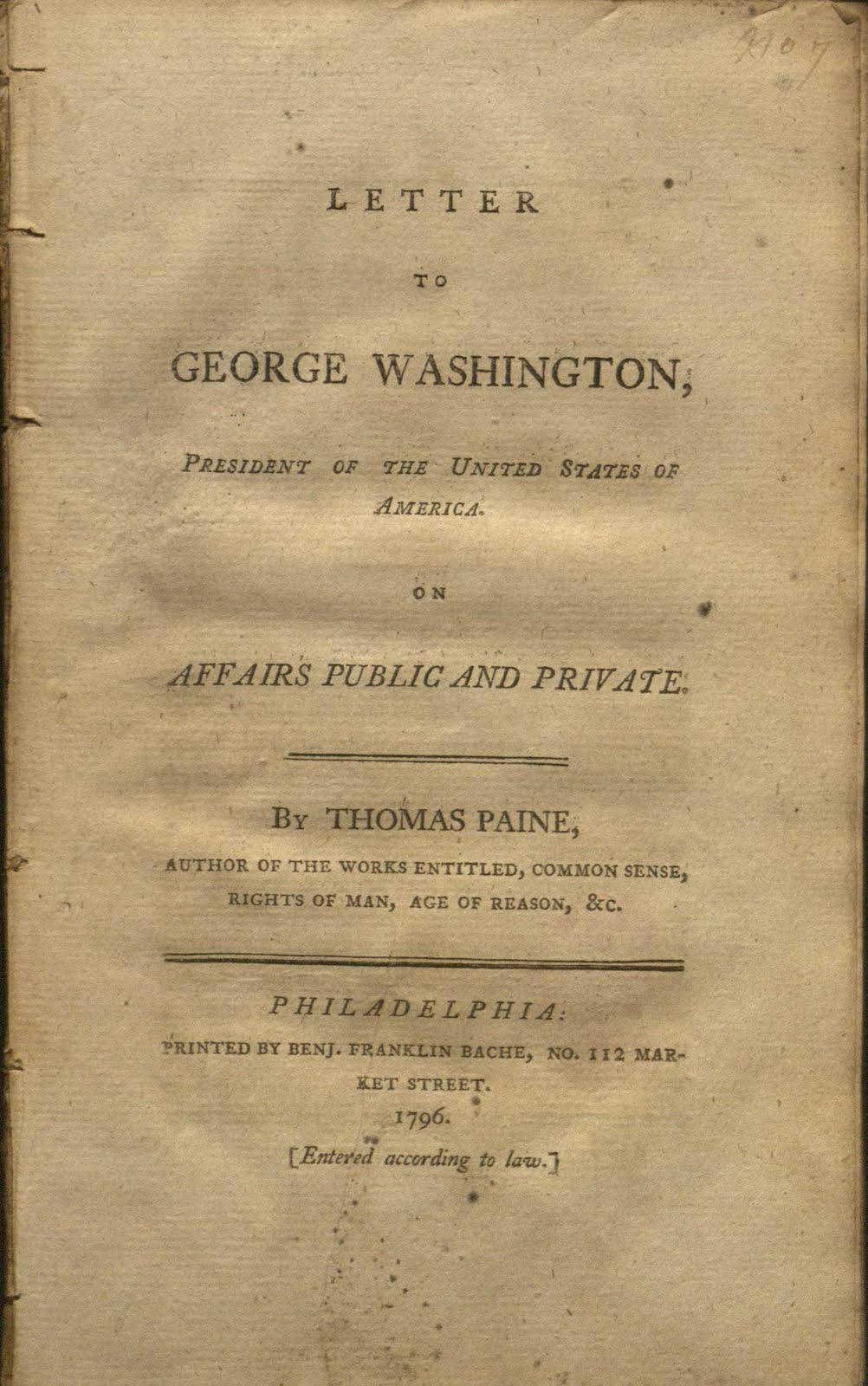

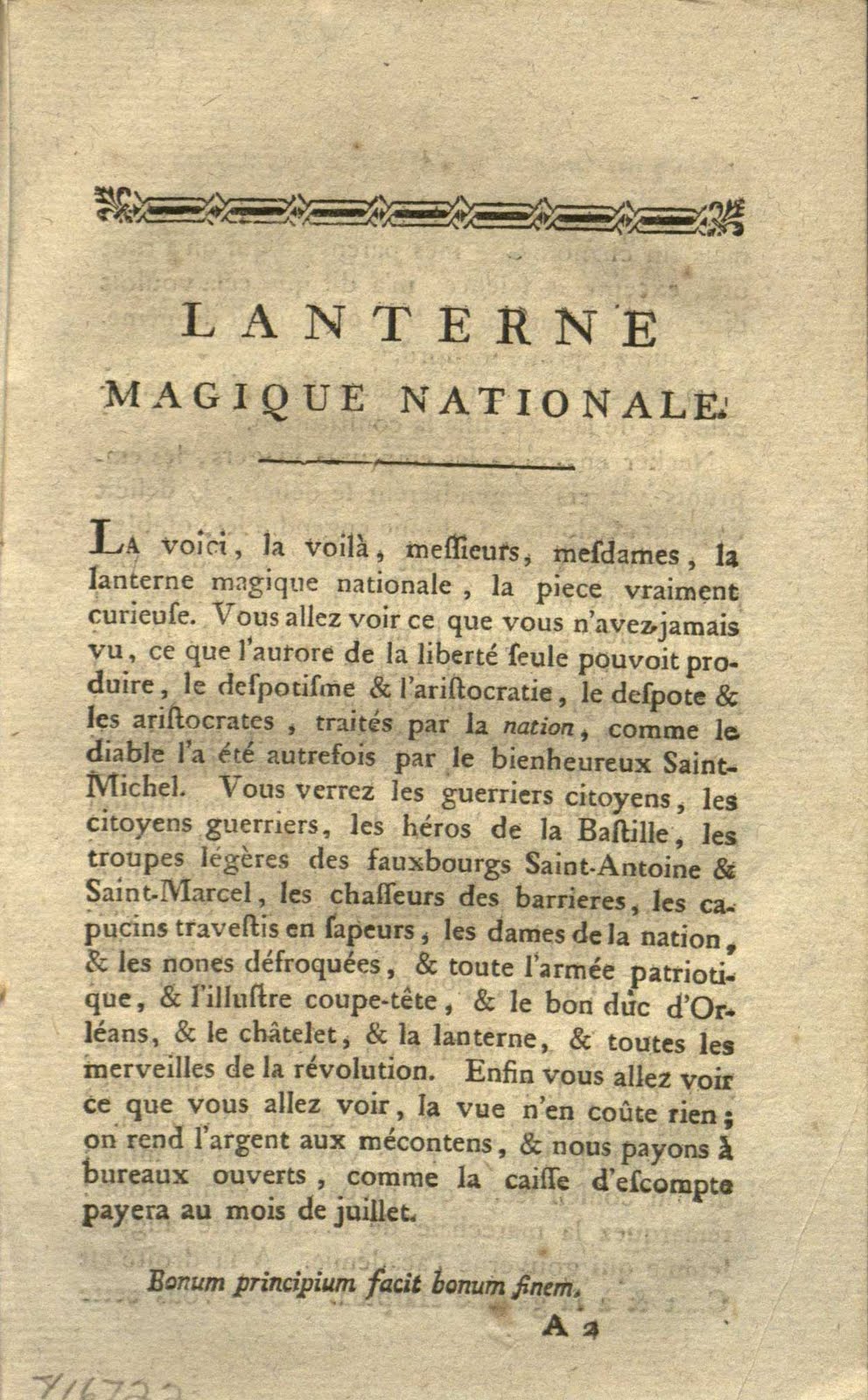

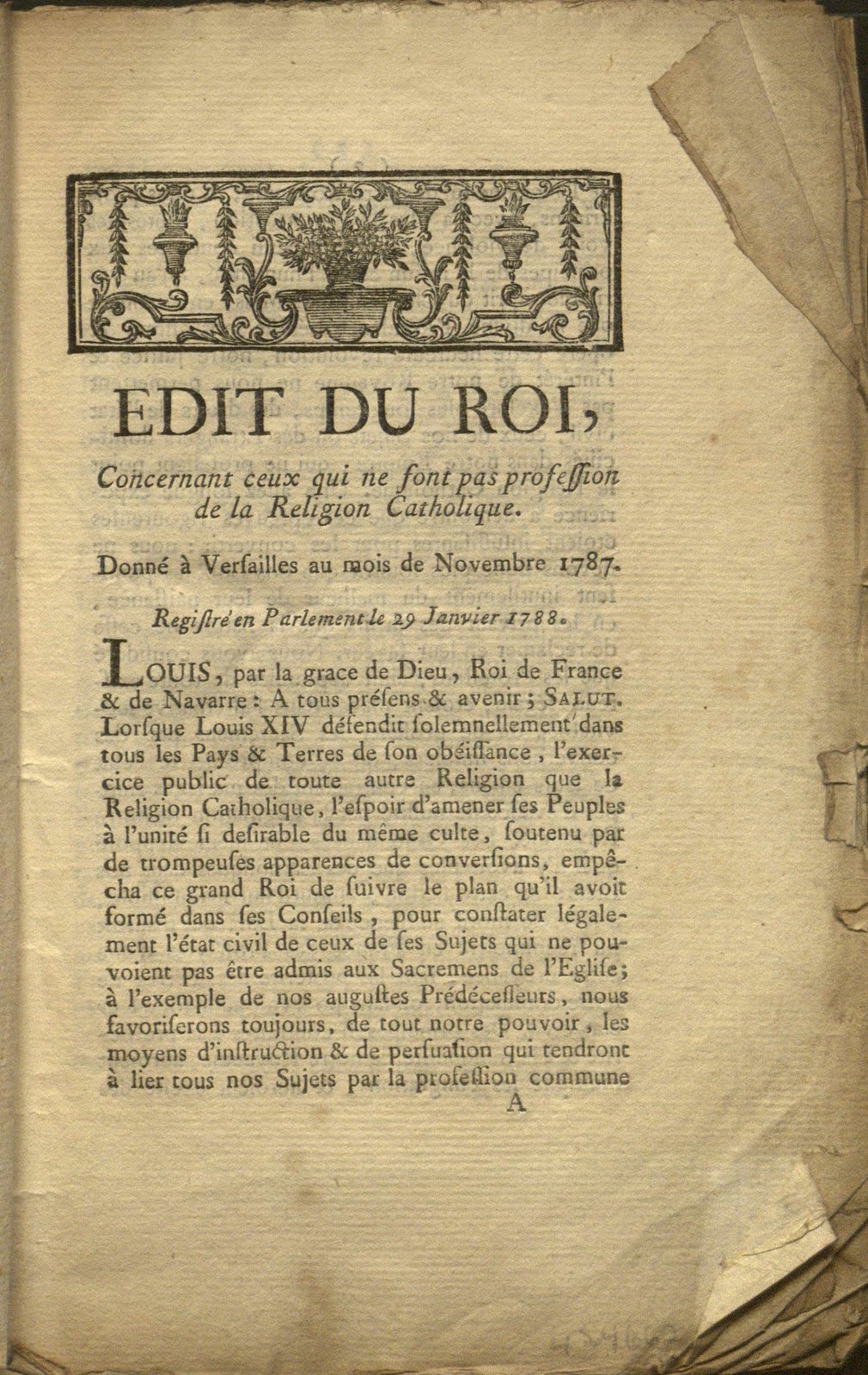

The pamphlets deal with politics, religious life, literature and intellectual life, among other topics. A great many of the pamphlets are official publications of the revolutionary government dealing with justice, law and public order as well as the internal politics of France during a dynamic and sometimes chaotic period of the country's history. The collection contains political tracts by authors including Thomas Paine, Jacques Necker, Mirabeau and King Louis XVI. Most of the pamphlets deal with the period of 1789-1799 and discuss issues such as the storming of the Bastille, the execution of Louis XVI and the flight of the Count of Artois (later Charles X), the Terror and the wars of the late 1790s. It includes several pamphlets describing various aspects of and events in the city of Bordeaux both before and during the Revolution, highlighting in particular the process of modernization and state centralization. Also in evidence are a great number of pamphlets concerning religion, especially the position of Catholics under the revolutionary government. Each category of documents provides a different perspective on this period, and the collection will likely be of particular interest to those with interests in the Enlightenment, urban history, monarchism and the counterrevolution, or the history and politics of secularization. Most of the documents are in French and nine are in English.

The pamphlets deal with politics, religious life, literature and intellectual life, among other topics. A great many of the pamphlets are official publications of the revolutionary government dealing with justice, law and public order as well as the internal politics of France during a dynamic and sometimes chaotic period of the country's history. The collection contains political tracts by authors including Thomas Paine, Jacques Necker, Mirabeau and King Louis XVI. Most of the pamphlets deal with the period of 1789-1799 and discuss issues such as the storming of the Bastille, the execution of Louis XVI and the flight of the Count of Artois (later Charles X), the Terror and the wars of the late 1790s. It includes several pamphlets describing various aspects of and events in the city of Bordeaux both before and during the Revolution, highlighting in particular the process of modernization and state centralization. Also in evidence are a great number of pamphlets concerning religion, especially the position of Catholics under the revolutionary government. Each category of documents provides a different perspective on this period, and the collection will likely be of particular interest to those with interests in the Enlightenment, urban history, monarchism and the counterrevolution, or the history and politics of secularization. Most of the documents are in French and nine are in English.

A variety of social, economic and political pressures came to a head in 1789 when France's massive foreign debt forced King Louis XVI to call the Estates General, an assembly representing the "estates" of the nobility and the clergy as well as the "Third Estate" of commoners. Despite the much greater number of people represented by the Third Estate, each estate was given equal representation within the Estates General. The relative weakness of the royal government put the increasingly wealthy and powerful third estate (led by the urban bourgeoisie and a rising merchant class) in a position to make demands. In response to what was widely viewed as the outsized power of the clergy and nobility, the Third Estate severed itself from the other two estates and formed a National Assembly claiming to speak for the people of France and against the entrenched interests of the church and the nobility. What followed was a rapid series of political developments that eventually led to the overthrow of the French monarchy and the installation of a secular republic. The period of the revolution saw the promulgation of a wide range of political ideas and positions, as well as an outpouring of pamphlets intended to popularize these ideas and exhort the public to action. Political and social change was accompanied by a revolution in print, as the popular press came to occupy an increasingly important role in French public discourse and political culture.[1]

A variety of social, economic and political pressures came to a head in 1789 when France's massive foreign debt forced King Louis XVI to call the Estates General, an assembly representing the "estates" of the nobility and the clergy as well as the "Third Estate" of commoners. Despite the much greater number of people represented by the Third Estate, each estate was given equal representation within the Estates General. The relative weakness of the royal government put the increasingly wealthy and powerful third estate (led by the urban bourgeoisie and a rising merchant class) in a position to make demands. In response to what was widely viewed as the outsized power of the clergy and nobility, the Third Estate severed itself from the other two estates and formed a National Assembly claiming to speak for the people of France and against the entrenched interests of the church and the nobility. What followed was a rapid series of political developments that eventually led to the overthrow of the French monarchy and the installation of a secular republic. The period of the revolution saw the promulgation of a wide range of political ideas and positions, as well as an outpouring of pamphlets intended to popularize these ideas and exhort the public to action. Political and social change was accompanied by a revolution in print, as the popular press came to occupy an increasingly important role in French public discourse and political culture.[1]

These developments were used not only by the revolutionaries and the radical philosophes but also by their enemies on the monarchist right and among French Catholics. Some of the most unusual and fascinating documents in the collection are written from the perspective of French Catholic women, a group whose story is often overshadowed by traditional narratives of the French Revolution. During the course of the Revolution, the church was increasingly subjugated to the state under the policy of "de-Christianization." Clergy were required, beginning in July 1790, to sign an oath of loyalty to the state. Those who refused (known as nonjuring clergy) were subject to the penalty of death. This oath, outlined in the so-called "Civil Constitution of the Clergy," caused a schism between those who agreed to take it and those who refused, and this split occasioned a heated debate over the place of the Church in politics and society. At the same time, the demise of the old regime and the institution of a "republic of virtue" marked a large shift in women's positions in society. The Church had long been a sphere in which women had a degree of influence, both as worshippers and as members of holy orders. The church's rigid patriarchal structure nonetheless provided women with a number of potential positions in which they could exercise socially meaningful power. Nuns cared for the sick and educated children, while laywomen who attended mass provided a link between ecclesiastical authority and the realm of home and family. The new regime, inspired in part by the writings of rationalist philosophes such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, likewise consigned women to a subordinate position.2 However, its reforms also threatened spaces such as the Church that had provided a measure of independence and social importance to women's lives. Two pamphlets written in the voices of Catholic women provide differing perspectives on this phenomenon, and together offer fascinating insights into the state of gender relations, political culture and public religion during the Revolution.

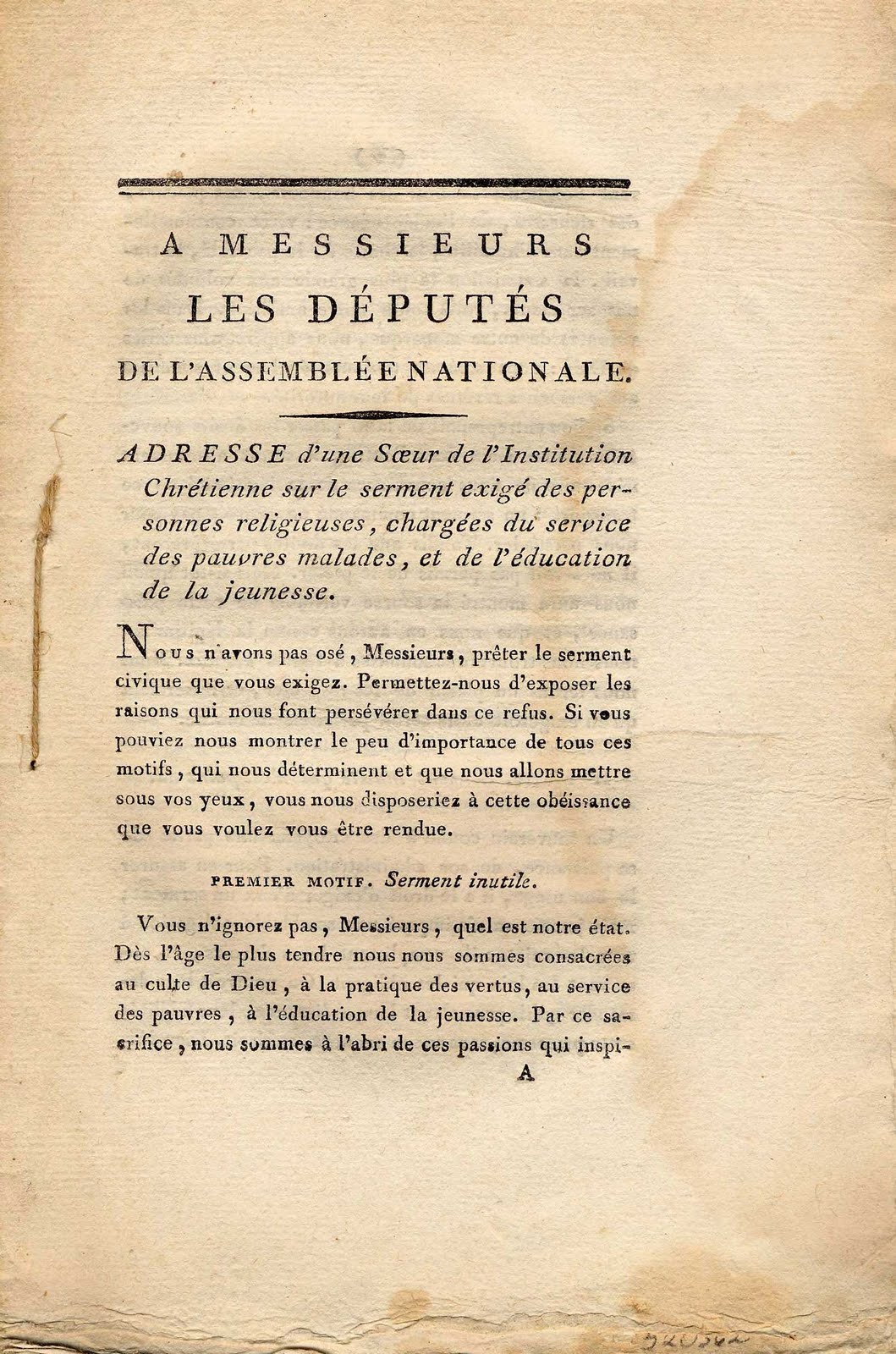

The first of these pamphlets is undated and deals primarily with the oath required of clergy by the Civil Constitution during the early period of the Revolution, before the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793. It begins, "To Messieurs the Deputies of the National Assembly: Address of a sister of the Christian Institution on the subject of the oath required of religious persons, charged with the service of the sick poor and with the education of the youth." [1] She goes on to describe the Church's integral role in society, as well as its links to the monarchy. "From the most tender age we have consecrated ourselves to the cult of God, to the practice of virtues, to the service of the poor, in the education of the youth. For this sacrifice, we are sheltered from the passions that inspire pride, love of honors, pleasures, riches, independence: living continually in humility, chastity, poverty, work, submission in the extreme to the wills of our superiors, here is all of our ambition. In the will of our monarch, we perceive that of God." Thus, "if one would undertake to cause the sovereign rights to pass from one hand to another, then it would be absolutely necessary to convince us of the legitimacy of that transport." (2) She argues that the civil constitution "will not suffice" to convince the clergy of the legitimacy of the new regime. If the clergy cannot accept the legitimacy of those in power, then it would be "useless" to ask them to swear an oath to that power. She then launches a sustained critique of the oath itself, arguing that it is "unusual and not owed" to the authorities, that it is "unintelligible" in addition to being illegal and impractical. Citing its "irreligious" and anti-Catholic tone and implications, she further elaborates that the oath is "anti-monarchical," arguing that, "this (oath) is to abolish, to annihilate in its foundations the monarchy itself." The pamphlet argues that the Catholic faith and the authority of the church form the basis of all legitimate government, and "honest citizens, who believe in God" cannot be expected to approve of any effort to undermine either the church or the monarchy.

The first of these pamphlets is undated and deals primarily with the oath required of clergy by the Civil Constitution during the early period of the Revolution, before the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793. It begins, "To Messieurs the Deputies of the National Assembly: Address of a sister of the Christian Institution on the subject of the oath required of religious persons, charged with the service of the sick poor and with the education of the youth." [1] She goes on to describe the Church's integral role in society, as well as its links to the monarchy. "From the most tender age we have consecrated ourselves to the cult of God, to the practice of virtues, to the service of the poor, in the education of the youth. For this sacrifice, we are sheltered from the passions that inspire pride, love of honors, pleasures, riches, independence: living continually in humility, chastity, poverty, work, submission in the extreme to the wills of our superiors, here is all of our ambition. In the will of our monarch, we perceive that of God." Thus, "if one would undertake to cause the sovereign rights to pass from one hand to another, then it would be absolutely necessary to convince us of the legitimacy of that transport." (2) She argues that the civil constitution "will not suffice" to convince the clergy of the legitimacy of the new regime. If the clergy cannot accept the legitimacy of those in power, then it would be "useless" to ask them to swear an oath to that power. She then launches a sustained critique of the oath itself, arguing that it is "unusual and not owed" to the authorities, that it is "unintelligible" in addition to being illegal and impractical. Citing its "irreligious" and anti-Catholic tone and implications, she further elaborates that the oath is "anti-monarchical," arguing that, "this (oath) is to abolish, to annihilate in its foundations the monarchy itself." The pamphlet argues that the Catholic faith and the authority of the church form the basis of all legitimate government, and "honest citizens, who believe in God" cannot be expected to approve of any effort to undermine either the church or the monarchy.

Thus the pamphlet, through the conceit of criticizing the oath alone, in fact launches an all-out attack on the legitimacy and the morality of the revolution. "In overturning the throne of our sovereign, you do away as well with all of the degrees (of dignity) that elevate the greatest lords around his majesty." (14) In undermining and imposing limitations on the church and the monarchy, the assembly undoes the order of society; it "confounds all of the ranks and overturns all of the orders of the citizens." (14) She argues for the necessity of hierarchy in society, based on the "natural" dependency of the servant on the master, the plaintiff on the judge and the citizen on the king. When the equal rights of man are declared, this natural order is overturned.

Thus the pamphlet, through the conceit of criticizing the oath alone, in fact launches an all-out attack on the legitimacy and the morality of the revolution. "In overturning the throne of our sovereign, you do away as well with all of the degrees (of dignity) that elevate the greatest lords around his majesty." (14) In undermining and imposing limitations on the church and the monarchy, the assembly undoes the order of society; it "confounds all of the ranks and overturns all of the orders of the citizens." (14) She argues for the necessity of hierarchy in society, based on the "natural" dependency of the servant on the master, the plaintiff on the judge and the citizen on the king. When the equal rights of man are declared, this natural order is overturned.

The pamphlet alleges that the oath is "the result of an awful conspiracy" perpetrated by a coalition of Lutherans, Calvinists and Jansenists. (20) Their disrespect for the authority of the Catholic Church and thus for the principle of authority itself has led them to oppose "all sovereigns," and so they conspire to dismantle the place of the Church in society against the will of the king. The conspiracy is said to reach all the way to the top, in the form of a "man from Geneva" (most likely the reformist royal minister Jacques Necker) who was "placed" close to the king following the American Revolution and worked from within the government to begin dismantling the old regime, expanding the representation of the 3rd estate in the Estates General and otherwise undermining the natural order in the name of the "new philosophy," (27) the impious tenets of which include individual liberty and freedom of the press. Such conspiratorial thinking seems to presage much of the anti-Protestant, anti-masonic and even anti-Semitic rhetoric that would later come to characterize French right-wing propaganda.

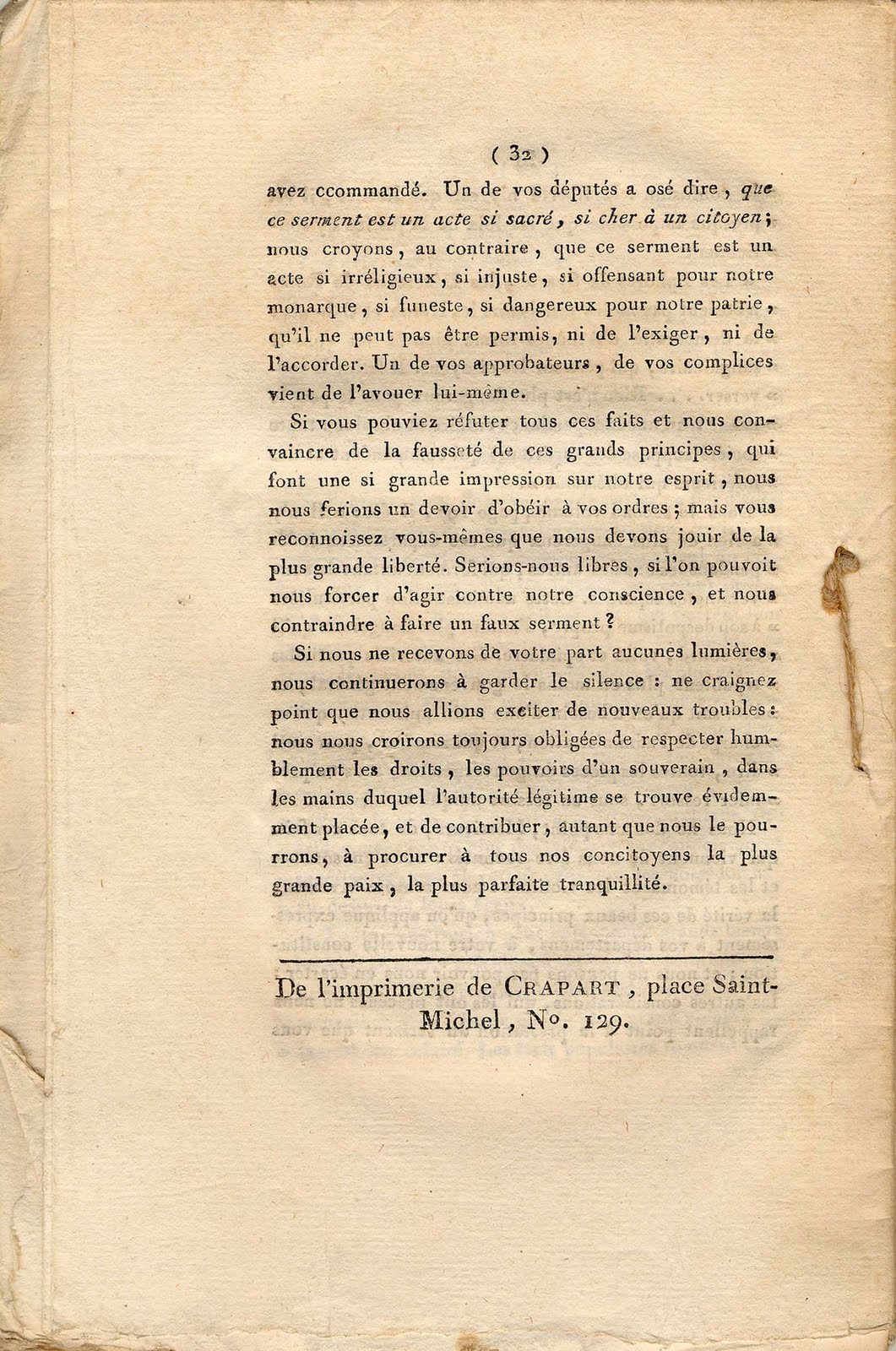

The final section, "An oath (that is) totally inopportune/inadequate (impolitique)," notes how, "One of your deputies has dared to say, that this oath is an act so sacred, so dear to a citizen. We believe, on the contrary, that this oath is an act so irreligious, so unjust, so offensive to our monarch, so disastrous, so dangerous for our country (patrie), that it cannot be permitted either to exist or to be granted." (32) She challenges the reader to convince her and the rest of the clergy otherwise, finishing by saying that, "If we do not receive any illumination from you, we will continue to keep silent: fear not that we will excite new troubles: we believe ourselves to always respect the laws, the powers of the sovereign." (32) In spite of this apparent conciliation, the point of the pamphlet is clear. No French government can be truly legitimate without its anointed ruler and his attendant social hierarchy, and devout Catholics owe their allegiance only to that system. A number of counterrevolutionary actions, including the bloody rebellion in the Vendée (1793-1796), suggest both the seriousness of the pamphleteer's intent and the very real nature of the threat of counterrevolutionary action by disaffected Catholic clergy and laypeople.

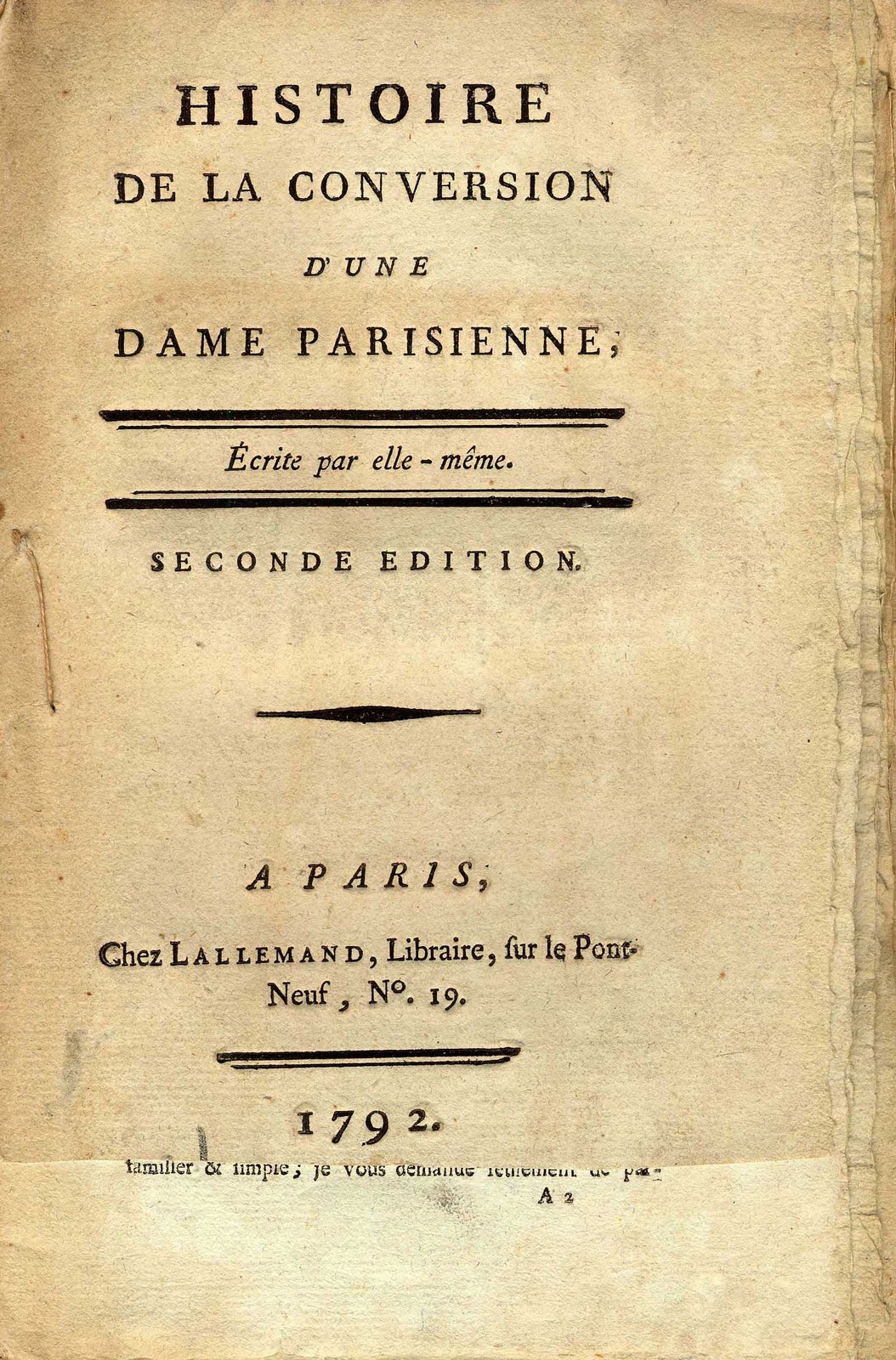

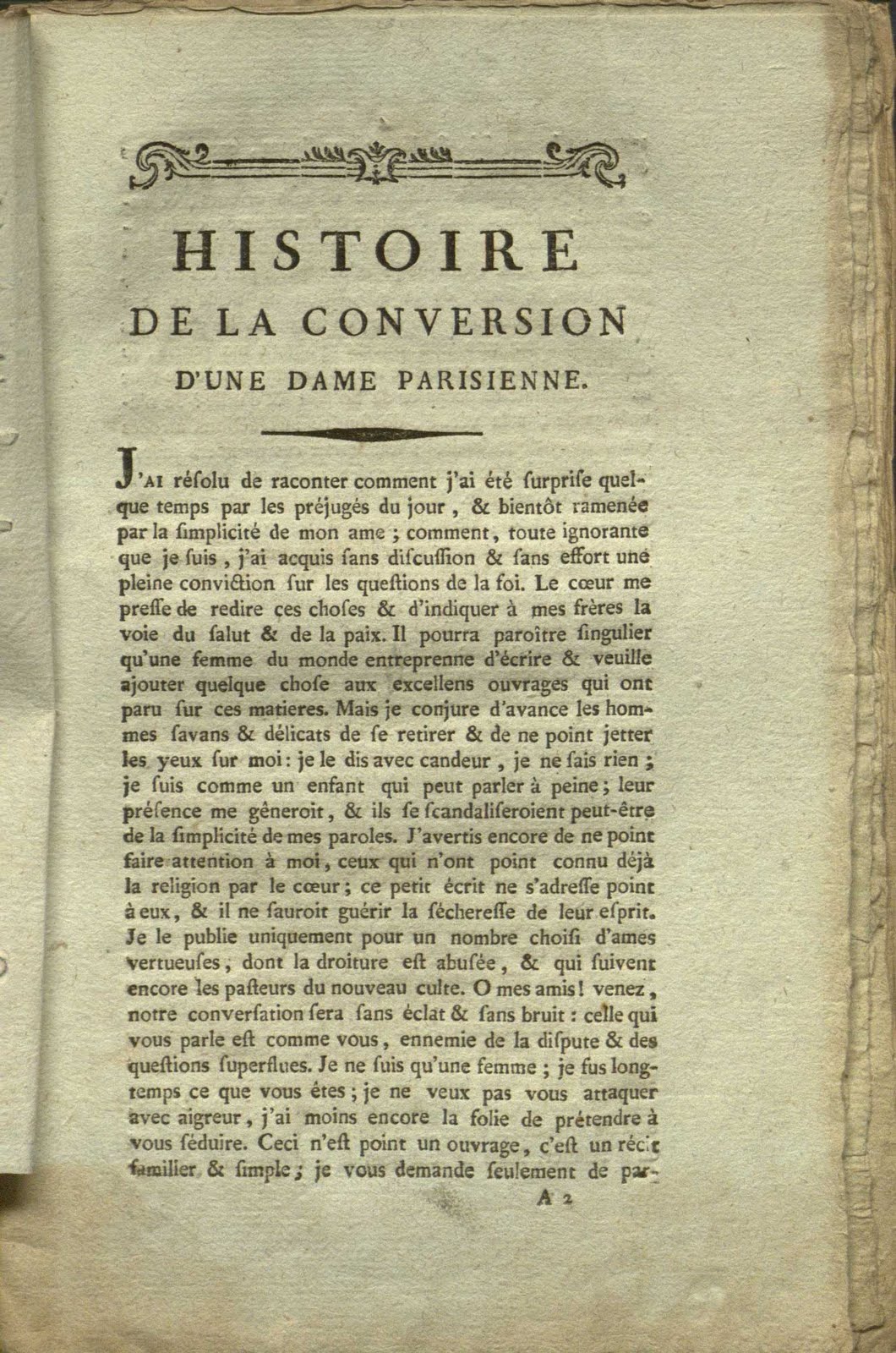

The second pamphlet is entitled “The History of the Conversion of a Parisian Woman, Written by Herself”. Written from the standpoint of a Catholic laywoman and published in 1792, it provides a different and no less fascinating window into the opinions and experiences of French Catholics during the Revolution. The woman in question, who likewise remains anonymous, begins by laying out the source of her need to speak publicly. In spite of her "total ignorance" and the "simplicity of (her) soul," she states that she has reached "without discussion or effort, a clear conviction on questions of faith." "The heart presses me to say these things again, and to indicate to my brothers the way of salvation and peace." (3) She goes on to detail her early support for the revolution and its values of liberty and progress. Like the nun in the earlier pamphlet, the key moment of transition for her was the institution of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the resulting schism in the Church. She tells the story of the moral conundrum she faced, and her quest to determine which side she ought to support. During the course of her soul-searching, she visits a church run by the new "constitutional" clergy. She comments on their inexperience and poor quality. She also notes their young ages and their corrupted mores, notably including the violation of their sacred celibacy with "monstrous marriages." (11) As a result of these factors and others, "everything became dead and cold in our churches" and people came to attend church due to habit, not due to feeling. "How is this reform?" she asks indignantly, "Is this what was promised?" (12) She addresses God himself, asking how it is possible that the ostensible regeneration of the Church has resulted in the removal from office of the true men of God. She faces a momentary crisis of faith, but "my God, your hand was on your servant; you were just as ardent to pursue me as I was ingenious to escape you."(12)

The second pamphlet is entitled “The History of the Conversion of a Parisian Woman, Written by Herself”. Written from the standpoint of a Catholic laywoman and published in 1792, it provides a different and no less fascinating window into the opinions and experiences of French Catholics during the Revolution. The woman in question, who likewise remains anonymous, begins by laying out the source of her need to speak publicly. In spite of her "total ignorance" and the "simplicity of (her) soul," she states that she has reached "without discussion or effort, a clear conviction on questions of faith." "The heart presses me to say these things again, and to indicate to my brothers the way of salvation and peace." (3) She goes on to detail her early support for the revolution and its values of liberty and progress. Like the nun in the earlier pamphlet, the key moment of transition for her was the institution of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the resulting schism in the Church. She tells the story of the moral conundrum she faced, and her quest to determine which side she ought to support. During the course of her soul-searching, she visits a church run by the new "constitutional" clergy. She comments on their inexperience and poor quality. She also notes their young ages and their corrupted mores, notably including the violation of their sacred celibacy with "monstrous marriages." (11) As a result of these factors and others, "everything became dead and cold in our churches" and people came to attend church due to habit, not due to feeling. "How is this reform?" she asks indignantly, "Is this what was promised?" (12) She addresses God himself, asking how it is possible that the ostensible regeneration of the Church has resulted in the removal from office of the true men of God. She faces a momentary crisis of faith, but "my God, your hand was on your servant; you were just as ardent to pursue me as I was ingenious to escape you."(12)

With some much-needed divine inspiration, she goes to meet with the "refractory" or non-juring clergy. She is immediately impressed by their courage in the face of persecution. They are characterized by sweetness and genuine commitment to their consciences, and are apparently devoid of the negative features ascribed to the constitutional clergy. She describes their suffering at length. Forced out of their jobs, they live on the charity of the faithful. Treated as pariahs, they are under a constant threat of violence from the population. In spite of everything, the refractory priests she meets are marked by strength and a spirit of sacrifice that convinces her of their sincerity and their moral correctness. She characterizes the stereotype that priests favor the monarchy and counter-revolution as a "ridiculous accusation" also unfairly applied to the poor, orphans and children. (15)

With some much-needed divine inspiration, she goes to meet with the "refractory" or non-juring clergy. She is immediately impressed by their courage in the face of persecution. They are characterized by sweetness and genuine commitment to their consciences, and are apparently devoid of the negative features ascribed to the constitutional clergy. She describes their suffering at length. Forced out of their jobs, they live on the charity of the faithful. Treated as pariahs, they are under a constant threat of violence from the population. In spite of everything, the refractory priests she meets are marked by strength and a spirit of sacrifice that convinces her of their sincerity and their moral correctness. She characterizes the stereotype that priests favor the monarchy and counter-revolution as a "ridiculous accusation" also unfairly applied to the poor, orphans and children. (15)

She questions one of the refractory priests on why he prefers his wretched state to signing the oath. He responds that he is content and that his conscience is at peace. "For me salvation is better than good fortune.î Impressed by the authority of his speech and his ìmartyrís zeal," she then decides to meet with a constitutional priest to hear his side of the story. She confronts him, and receives a mocking and condescending reply couched firmly in the language of reason and enlightenment. In response to her assertion of her views on scripture, he replies, "oh, oh, so you are a theologian! Well then! Madame, since you seem so knowledgeable, let's see how you reply to some little arguments that Iíve prepared for you!" (22) He goes on to make a series of esoteric theological claims that seek to undermine the historical authority of the Pope and other concepts of importance to traditionalist Catholics. To support his claims, he cites a vast body of sources and appears to think himself quite the intellectual. In response, the pamphlet's author declares that his argument, couched in the terms of enlightenment and reason, is in fact composed of "sophistries and errors." (23) Finding herself unable to understand and refute the priest's argument on his own terms, she decides that his true intent was to dazzle her with a "useless erudition" (24) and thus confuse her into accepting falsehoods. This anti-intellectual note is echoed several times in the piece, as she criticizes, "that vain science that nourishes a curiosity that is even more vain." (24) The vain science in question is likely similar to that "new philosophy" opposed by the nun in the prior pamphlet. The author determines that people are often misled by constitutional priests because of their dishonest deployment of the language of enlightenment.

Realizing the importance of her choice between the two sides for the salvation of her soul, she experiences a feeling of despair. She consults a book entitled The “Thoughts of Father Bourdelou” for guidance, and determines that the doctrine of the "infallible teachings" of the church has the "je ne sais quoi of the divine." She describes how Catholic dogma feels, to her, "born of all of the old thoughts regarding religion and God" and she argues in favor of the timeless values of "renunciation of myself, denial of my own light, a child's simplicity and submission to my superiors." (28) She realizes that "the authority of the church must be truly expressed." In order to assure this, the so-called "constitutional clergy" must be exposed as being in error and thus heretics.(29) She concludes, "now, reason whoever may, dispute whoever dares; for me, I am with the Church, I march with the Church, obedience suits me better than science, my submission instructs me better than all the books in the world." (31) Praising "virtuous ignorance" and the light of common sense, she describes herself as lost and found again.(32-33) After an intense conversion experience in which she "prostrated myself on the paving stones of the church," uttering a "profound and tender" prayer. (34)

Armed with the simple truth of her religion, she finds herself compelled to spread the word. She is forced to confront her rationalist and pro-revolutionary husband, the first mention of whom occurs nearly at the end of the pamphlet. She is compelled to be honest with him, realizing that although she loves him she loves Christ more. Confident and candid, she describes her experiences to her husband with sweetness and humility. He responds with violent anger to her conversion, accusing her of being a fanatic.(36) However, she holds up under pressure and eventually impresses him with her ardent faith and peaceful bearing. She convinces him not with reasons but with "sentiments," meeting anger with love in good Christian form. Putting the lie to his stereotypical understanding of ultramontanes, she eventually convinces him to convert as well. Through faith, she exercises power over not only his faith but also his politics and his entire worldview. (37) Her husband, however, approaches his faith from a place of reason and becomes well educated on religious matters, as is his right as a man. His faith, "quite rare among the men of the world," impresses his wife.

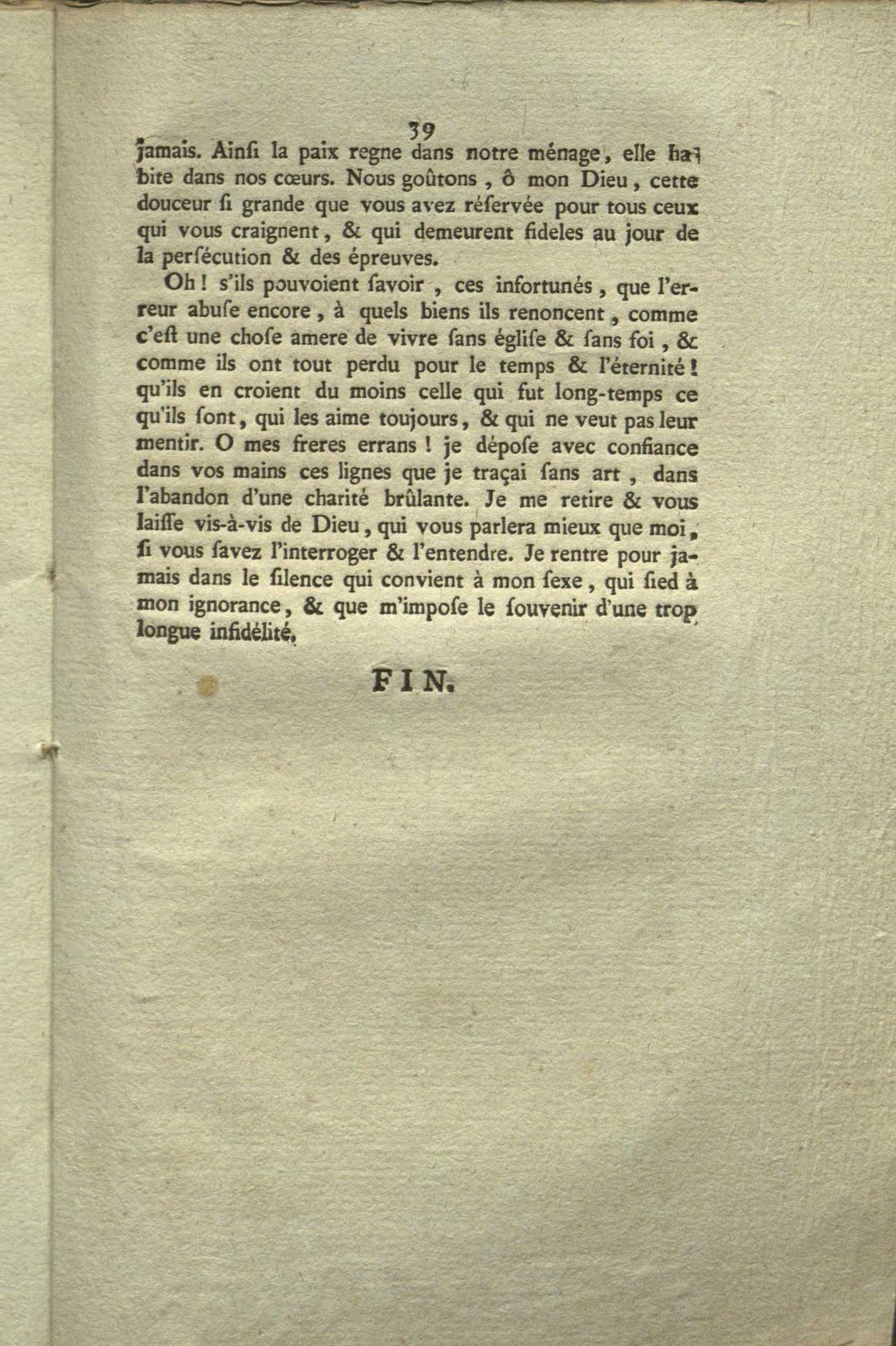

The pamphlet concludes with an exhortation to Catholics to "live like him (Jesus) because we are persecuted like him." She notes that she and her husband rarely speak of "affairs of state.î"They "defy the exaggerated combinations of a profane politics. The hand of men seems to us too fragile to place our confidence and our support in." (39) Abandoning the simple and strident monarchism of the prior pamphlet, she instead argues for disengagement from politics and a basic acceptance of the new republican order. Her opposition to the state is conditional upon the state's unwarranted meddling in religious matters. Thus she, unlike the nun in the prior pamphlet, appears to have accepted the liberal construct of the separation of church and state and deploys that reasoning in defense of her faith rather than seeing it as a threat.

She concludes: "Oh my errant brothers! I place these lines into your hands with confidence that I have traced, without art, in the abandon of my burning charity. I retire and leave you face-to-face with God, who you will speak (with) better than I, if you know how to ask and to listen. I return forever into the silence that suits my sex, befitting my ignorance, and that is imposed upon me by the memory of my too-long infidelity." (39) This line, addressed (like the entire pamphlet) to the men of France, contains a number of possible readings. On one hand, she has agreed to silence herself on political and religious matters, having said her piece. Yet her real and potential influence over men (as evidenced by her conversion of her husband) is considerable, and the pamphlet suggests that exercising that influence is a righteous path for women of the world like her. In the realm of the conscience, there is room not only for women's wills to be realized but for women to exercise power over men and to influence political processes. The defiantly masculine "virtue" and philosophy of the republic is thus contrasted to (and shown to be in conflict with) the peaceful and loving (traditionally feminine) virtues of the Church and Christian faith, and ultimately powerless against them. Taken together, these two pamphlets in the voices of French Catholic women provide a unique counterpoint to the usual telling of the story of the French revolution, bringing into focus the particular challenges faced by women and people of faith when confronted by a new regime that was often hostile to both faith and femininity.

She concludes: "Oh my errant brothers! I place these lines into your hands with confidence that I have traced, without art, in the abandon of my burning charity. I retire and leave you face-to-face with God, who you will speak (with) better than I, if you know how to ask and to listen. I return forever into the silence that suits my sex, befitting my ignorance, and that is imposed upon me by the memory of my too-long infidelity." (39) This line, addressed (like the entire pamphlet) to the men of France, contains a number of possible readings. On one hand, she has agreed to silence herself on political and religious matters, having said her piece. Yet her real and potential influence over men (as evidenced by her conversion of her husband) is considerable, and the pamphlet suggests that exercising that influence is a righteous path for women of the world like her. In the realm of the conscience, there is room not only for women's wills to be realized but for women to exercise power over men and to influence political processes. The defiantly masculine "virtue" and philosophy of the republic is thus contrasted to (and shown to be in conflict with) the peaceful and loving (traditionally feminine) virtues of the Church and Christian faith, and ultimately powerless against them. Taken together, these two pamphlets in the voices of French Catholic women provide a unique counterpoint to the usual telling of the story of the French revolution, bringing into focus the particular challenges faced by women and people of faith when confronted by a new regime that was often hostile to both faith and femininity.